By Gianluca Piccolino (University of Trieste) and Leonardo Puleo (Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies)

It is still unclear whether Mario Draghi will lead the next Italian government. The attempts to form another government led by Giuseppe Conte failed for the same reasons which led to the collapse of his second cabinet, namely the resoluteness of the small yet crucial party led by Matteo Renzi to support Conte and his plans to manage the Next Generation EU funds. In this framework, a government led by the former President of the European Central Bank is widely seen as the last option to avoid a snap election.

The decision taken by the President of the Republic Sergio Mattarella to assign to Draghi the hard task to find another parliamentary majority is not entirely surprising for at least two reasons. First, it was commonly known that Draghi was willing to play a role in the political arena since he left the ECB in 2019, even though most of the commentators considered him as the main candidate for the (parliamentary) election of the President of the Republic in 2022. Second, the temptation to resort to technocratic solutions is anything but new in the recent Italian political history. Table 1 shows a short description of the cabinets formed in Italy in the last thirty years.

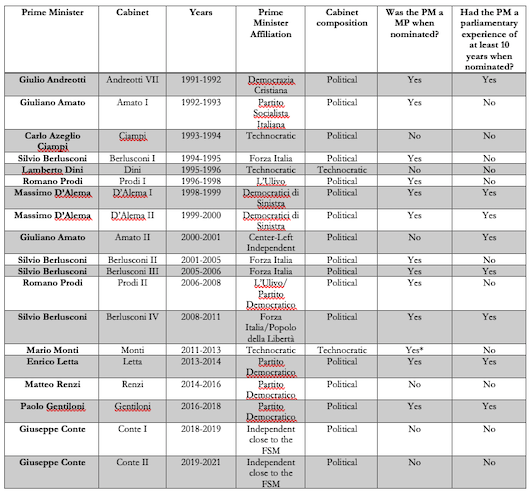

Table 1. Italian cabinets formed in the last thirty years (1991-2021)

Sources: Casal Bértoa (2021) and McDonnell and Valbruzzi (2014); camera.it; senato.it; governo.it

* Mario Monti was nominated senatore a vita (senator for life) for life few days before taking office.

Out of nineteen cabinets formed in this period, three were led by technocratic Prime Ministers without any political affiliation – Carlo Azeglio Ciampi (1993-1994), Lamberto Dini (1995-1996) and Mario Monti (2011-2013) – and the last two had a full technocratic composition. Significantly, Ciampi and Dini had high responsibilities within Bank of Italy – serving together as governor and director-general for several years – the same institution which was later led by Mario Draghi and served as his launchpad for the ECB.

The linkage between the Prime Minister and the Parliament too has been put in strain in this period. Six cabinets were led by a Prime Minister who was not a Member of the Parliament, and even eleven were led by a Prime Minister without a parliamentary experience of at least ten years at the time of the nomination. It is a clear discontinuity with the so-called First Republic (1948-1992). In this period, no government was led by a Prime Minister chosen outside the Parliament until its last cabinet led by Ciampi and parties usually assigned this role to politicians with a long parliamentary history.

Moreover, looking at the composition of the cabinets, the relationship between technocracy and the Italian case in recent years acquires the contours of a pathological normalcy. On average, cabinets of the Second Republic have had a much higher share of technocratic ministers compared to the cabinets of the First Republic. In this framework, it is paradigmatic the case of the powerful Ministry of Economy and Finance. Since its foundation in 2001, seven out of nine ministers of the MEF had no formal political experience before the appointment, but had rather have prolific careers within academia, top-level bureaucracy, or international economic institutions.

This feature goes hand in hand with another one, the role of populism in the Italian politics. Since the 1990s, both pundits and scholars have indeed indicated Italy as a laboratory, a paradise or even a promise land for populists. The list of relevant populist actors and parties in Italy is striking long if compared with the other European countries, encompassing both left-wing and right-wing and even “pure” forms of populism. How can a technocratic tradition coexist with a populist tendency? Is this an irony of the history? Or is it possible to establish some theoretical and empirical links between populist and technocratic mentalities?

In a recent article, Daniele Caramani investigated the relationships existing between populism and technocracy and – specifically – the differences setting apart them from liberal democracy. The theoretical rationale behind technocracy derives from the assumption that a unitary common interest indeed exists. The best political solutions can be acquired through the competence, that certainly does not lack to a technocratic government. In this respect, there is no room for plural – and conflictual – interests. Looking at reality through such a prism, whatsoever conflict can be harmonized through the policies offered by technocrats, removing the responsibility from the irresponsible politicians. This monism mirrors quite close to the populist perspective. In populists’ eyes, the public good is represented by the will of the people, that is portraited as just one indefinite entity. It is even more interesting to look at the legitimacy sources of both populism and technocracy. The former finds it – clearly – in the people and the latter in the alleged technocrats’ competence. The problem here is that in both populism and technocracy there is little need for accountability. This result evident when technocracy descends from theory to its empirical incarnations: the technocratic government are by definition detached from the electoral process. Precisely for this reason they are often invoked to implement unpopular policies, and in this respect, they epitomize the parties’ failure.

This theoretical sketch fits fairly well with the Italian experience. The cabinets led by Ciampi, Dini, and Monti enjoyed bipartisan support and represented indeed a response to both political and economic crises. The cabinet led by Ciampi was formed with the explicit aim to overcome the legitimacy crisis followed by ‘mani pulite’ (clean hands) investigation, that revealed a nation-wide system of illegal party’s founding, and to deal with the precarious situation of the Italian economy and its currency. The last cabinet of the First Republic intervened to restore the political system – discredited by corruption scandals – in order to provide a new start for the party politics of the – so-called – Second Republic. Dini’s fully technocratic cabinet was justified by the profound divisions and the governmental inexperience of the centre-right led by Silvio Berlusconi, which collapsed on the pension reform later approved during the technocratic cabinet. Finally, yet importantly, Monti cabinet initially was portraited as a redeeming hero to overcome the credibility crisis of the last Berlusconi government and well-equipped to solve the Italian budgetary problems but was then perceived as a wrecking ball against the welfare state. It is all but accidental that Monti’s government has been followed in 2013 by one of the elections exhibiting the highest rate of volatility in Europe, marking the breakthrough of the Five Star Movement.

If the previous technocratic experiences were thus linked to the inability of political parties in performing their governmental responsibilities, the situation looks different for a hypothetical Draghi cabinet. The main controversy revolves indeed around the management of the Next Generation EU funds. In this case, it seems that no party wants to leave to their competitors the benefits in managing more than 200 billion euro. What will be next it is hard to say, a plain consideration is although possible: if politics abdicate – once more – in exercising its responsibilities in programming the biggest financial plan since the history of the Italian Republic, then political instability will likely knock again at the door.

Once home of some of the most powerful political parties in democratic countries, Italy now routinely manages its main political crises by asking technocrats to lead the national government. No major Western European country is following a similar path, and few countries in the world have adopted technocratic solutions for their governments so often. Moreover, it is unclear if the technocratic governments helped to mitigate the Italian political instability or instead contributed to worsen it.

In its tradition of technocratic governments, the Italian political debate has been marked by two narratives. On the one hand, the alleged irresponsible behaviour displayed by political parties. On the other hand, the salvific role of technocrats, portrayed as last resort (impartial) problem solvers. This peculiarity shows all the fragilities of the country to deal with its crucial economic and political issues. Ultimately, it risks to reduce and vilify the role of politics in the management of public affairs, widening the lack of trust toward political parties and the political apathy of the electorate.

Photo source: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-55912951