By Lukas Lauener (Swiss Centre of Expertise in the Social Sciences/University of Lausanne)

On 22 October, almost 5.6 million voters were called to elect the new Swiss Parliament for its 52nd legislative period. 46.6 percent of eligible voters participated in the elections, which is a small increase of 1.5 percentage points compared to 2019. It is by no means unusual for Swiss standards that turnout is below 50 percent, as many citizens prefer to participate in direct democratic votes on policy proposals (referendums and initiatives), leading to a certain trade-off between participation in popular votes and in elections. An empirical study showed that while around 16 percent of Swiss citizens participate in every vote and election, 64 percent do so selectively, i.e., they participate when they are interested by the issue(s) at stake, and only around 20 percent are complete political abstainers.

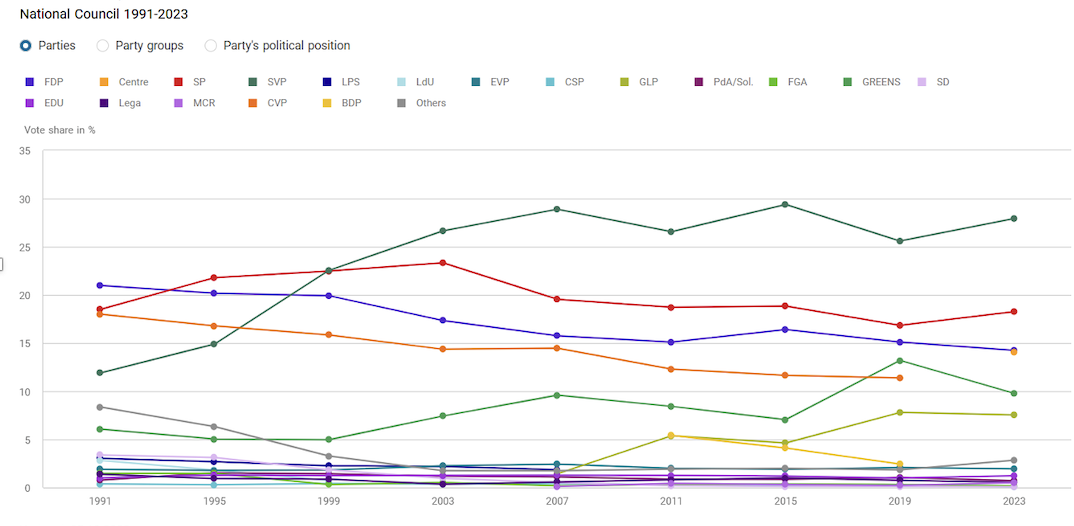

The two pole parties, the radical right populist Swiss People’s Party (SVP) and the left-wing Social Democratic Party (SP) got out as winners of the 2023 federal elections. While the two green parties, the left-wing Green Party (GPS) and the centrist Green Liberal Party (GLP), were clear winners of the previous federal elections in 2019, they are on the losers’ side this year. The former lost 3.4 percentage points and fell just below the psychologically important threshold of 10 percent (9.8 percent). It now holds 23 out of 200 seats in the Lower House of the Swiss Parliament, the National Council (minus 5 seats compared to 2019). The latter lost only 0.2 percentage points in vote (from 7.8 to 7.6 percent) shares but lost 6 seats in the National Council – due to unfavourable list coalitions – and now holds 10 seats (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Trend in party vote shares

Source: https://www.wahlen.admin.ch/en/2023/ch/parteistaerke-zeit

In the run-up to this year’s federal elections, three main issues played an important role in the Swiss voters’ perceptions: raising health costs, climate change, and immigration. Compared to four years ago, when during the election campaign almost exclusively the issue of climate change was being discussed in the media, there was undoubtedly a larger variety of political problems that were mediatised and at the forefront of candidates’ and parties’ campaign this year. Furthermore, two important movements that were characteristic for the massive 2019 gains for the Greens and Green Liberals, i.e., the climate strike and the women’s strike movements, had also tried to mobilise voters before this year’s elections, but clearly declined in radiance compared to four years ago. While the 2019 Swiss federal elections were labelled as “climate” and “women’s” elections, political analysists have described this year’s elections as “correction” elections pointing to the so-called “yo-yo” effect: This year’s winners were last time’s losers and vice versa.

The “yo-yo” effect applied to almost all major political parties running for elections. Switzerland’s strongest political force, the SVP, could increase its vote share from 25.6 to 27.9 percent (+2.3 percentage points), which translates into 9 additional seats (2019: 53 seats) in the Lower House. However, this only partly compensated for the SVP’s loss of 12 seats in 2019. The second strongest force, the SP, gained 2 seats and are now represented with 41 deputies in the National Council. Its vote share rose from 16.8 to 18.3 percent (+1.5 percentage points). Pollsters had predicted gains for the two pole parties already months before the parliamentary elections.

Small gains had also been predicted for the Centre Party which was formed in 2021 through the merger of two centre-right parties, the Christian Democratic Party (CVP) and the smaller Conservative Democratic Party (BDP). In the 2019 elections, the CVP achieved a vote share of 11.4 percent and the BDP 2.5 percent. Back then, both parties were on the losers’ side. For a long time, it had remained unclear whether the newly formed Centre Party would attain the same electoral strength as the simple addition of the vote shares of both original parties. Coming closer to the election day, pre-election polls showed that the Centre Party would indeed reach or even exceed this level. They predicted a neck-and-neck race for the third strongest political party between the Centre Party and the Liberals (FDP).

Who wins the race for the third place?

In the end, the Centre Party reached a vote share of 14.1 percent (+0.2 percentage points compared to the combined vote shares of the CVP and BDP in 2019) and is now represented with 29 deputies in the National Council (+1 seat). However, it missed the third place in the race for vote shares. As before, the FDP is the third strongest political force in the Swiss political landscape, when looking at vote shares. The Liberals reached 14.3 percent of vote shares and are now only just in front of the Centre Party. However, looking at their representation in the National Council in terms of seats, the FDP lost 1 seat and has now 28 deputies. In addition, the FDP is the only major political party that has not experienced the “yo-yo” effect: compared to the 2019 election results, it lost 0.8 percentage points and thus continues its long-term downward trend. In the last four decades, the Liberals lost every single federal election except for one (in 2015). Even though the Centre Party lost the race for the third place in vote shares, it won the race in terms of the number of representatives in the National Council. With 29 deputies, it is now just in front of the Liberals with 28 deputies.

On a more anecdotal note, the Centre Party was actually thought to be the third strongest political force for two and a half days. On the evening of election Sunday, the Federal Statistical Office (FSO) miscalculated party strengths due to an incorrect feed of data from the cantons. In the first statistics released by the FSO on Sunday evening, the Centre Party appeared to be 0.2 percentage points stronger (14.6 percent vote share) than the Liberals (14.4 percent). After the error was detected on Tuesday afternoon, the FSO recalculated party strengths and communicated the correct numbers on Wednesday. This error perhaps even accounted for a world premiere: the results of the last pre-election poll which was conducted three to four weeks before the elections were closer to the effective party strengths than the erroneous vote shares published by the FSO on Sunday evening. The corrected party strength statistics had however no influence on seat allocation for the National Council because the seats had already been (correctly) distributed in each canton individually on election Sunday.

(How) Do the election results influence policy-making in the next four years?

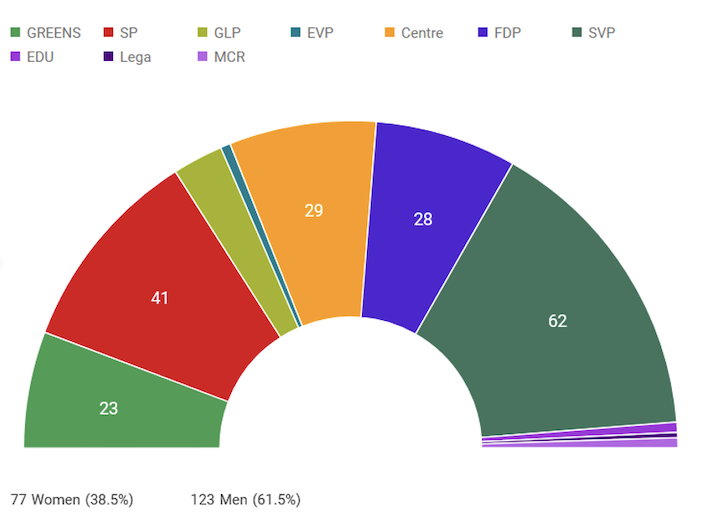

When looking at the strength of political blocks in the National Council, the right block consisting of SVP, FDP and other small rightist parties clearly gained in importance through this year’s elections. In the canton of Geneva, the populist radical right Geneva Citizens’ Movement (MCG) won 2 seats and in the canton of Zürich, the right-wing Federal Democratic Union (EDU) which allied with the “Mass-Voll” movement, a movement founded in the COVID-19 pandemic that strongly opposed any governmental measures to fight the pandemic, won 1 seat. Furthermore, in the canton of Ticino, the regionalist nationalist-populist Ticino League (Lega) could hold its seat in the National Council. All right-wing parties, i.e., SVP with 62 seats (+9), FDP 28 (-1), MCG 2 (+2), EDU 2 (+1) and Lega 1 (+/-0), now have 95 seats in the Lower House. For the upcoming legislative period, the right block will thus be 11 seats stronger than between 2019 and 2023. Importantly, it does however not reach a majority. This was the case last time, when the SVP and FDP hold a very slim majority of 101 seats in the National Council in the legislative period from 2015 to 2019.

On the other hand, the political centre and the left block both lost seats. The centrist parties overall lost 6 seats. The small gain of one seat for the Centre Party could not compensate the Green Liberal losses (-6). In addition, another centrist party, the Evangelical People’s Party (EVP) lost one of their three seats. The three centrist parties, i.e., the centre block, will have a total of 41 National Councillors in the upcoming legislative period, namely 29 Centre Party (+1), 10 GLP (-6) and 2 EVP (-1) representatives. The left block consisting of 41 Social Democrats (+2) and 23 Greens (-5) will have 64 deputies. With the seat losses of the two radical-left parties Solidarity in the canton of Geneva (-1) and the Swiss Party of Labour in the canton of Neuchâtel (-1), which will both not be represented in the Swiss Parliament anymore, the left block lost a total of 5 seats compared to the 2019 election results (see Figure 2). As it was the case in the last legislative period, the centre block will be able to assume the important role of “majority creators”. Either the Centre Party (which forms a parliamentary group together with the EVP) or the Green Liberals – on their own – can easily help the right block to a majority or the centre block can – jointly – ally with the Left.

Figure 2. Allocation of mandates

Source: https://www.wahlen.admin.ch/en/2023/ch/03-nr-mandatsverteilung

The Swiss public broadcast company (SRF) aptly described the new composition of the National Council as “more masculine, older, and more rural” than before. Indeed, the percentage of elected women decreased from 42 to 38.5 percent, the average age of National Councillors rose by almost one year and now attains 49.7 years and the ten largest Swiss cities are now represented with 49 instead of 55 deputies compared to four years ago. In the upcoming legislative period, it will certainly become more difficult for leftist and green demands in environmental, energy, and climate policy to find a majority. The Climate Protection Act adopted by a majority of 59 percent of Swiss voters on 18 June 2023, which sets a net-zero emission target by 2050, is an example of the direction that climate policy might take in the future: instead of new bans, incentives will be more likely to gain majority support. In addition, climate protection could increasingly gain the upper hand over the protection of the homeland and landscape in the future, for example when the expansion of renewable energies clashes with landscape or environmental protection concerns.

In terms of gender equality and housing policy, it also seems that left-wing demands will have a hard time in the next four years: state interventions to assure wage equality between men and women or governmental controls of apartment rents are unlikely to meet with majority approval in the new parliament. With the two pole parties strengthened in the elections, especially the pronounced anti-EU party SVP, and with the GLP as the only unreservedly pro-European party weakened, Switzerland’s already strained relationship with the EU is unlikely to improve quickly. In return, right-wing demands for more restrictive immigration and asylum policies are more likely to have an easier time in the next four years.

The October election is only (a bit more than) half of the story…

How and what new majorities will be possible for policy-making in the new legislative period does not only depend on the National Council but also on the Council of States which is the Upper House of the Swiss Parliament. Each canton has two representatives and the six so-called “semi-cantons” appoint only one representative to the Council of States. Elections to the Upper House are cantonal elections meaning that 24 cantons have their distinct form of a majority voting system to elect their senators, whereas two cantons (Neuchâtel and Jura) use a proportional system.

In the federal elections on 22 October, 29 out of the 46 senators were elected. The semi-canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden had already elected its representative in April at the Landsgemeinde, the cantonal public voters’ assembly. In another semi-canton, Obwalden, there was only one candidate, the incumbent senator, who ran for the election to the Council of States. He was therefore confirmed in office in a silent election. In the canton of Bern, none of the candidates achieved an absolute majority in the first election round. However, as all but the two best-placed candidates withdrew in the days following the election, there is no need for a second round anymore and the two remaining candidates were confirmed as State Councillors in a silent election. For the remaining 13 seats, a second round is necessary, so that only on 19 November we will know with certainty about the final distribution of seats in the Council of States. For the moment being the Centre Party has the most senators (10), followed by the FDP (9), SP (6), SVP (5), and the Greens (3). This order of party strengths is the same as before the Council of States elections and it will possibly not change (much) with the second tour.

What will the government look like?

In December after the parliamentary elections, the Federal Assembly, that is the National Council and the Council of States combined, elects the Swiss government, the Federal Council. The 7-member executive is a voluntary oversized coalition government composed according to the unwritten rule of concordance under which the strongest parties are represented in proportion of their electoral strengths. Since 1959 (with an interruption between 2008 and 2015), the so-called “magic formula” has been applied to distribute the seven governmental seats among the most important political forces of the country: the three largest parties are granted two seats and the fourth party gets one seat. At the moment, SVP, SP and FDP each have two representatives in the Federal Council and the Centre Party one. However, with the Centre Party being on almost exactly the same level of electoral strength (14.1 percent) as the FDP (14.3 percent), having even one more representative (29) in the National Council than the Liberals (28) and being most likely again the strongest political force in the Council of States, there is a lot of discussion among the parties and in the media whether the magic formula still makes sense and how it could be changed.

The Greens already called for a rethinking of the “magic formula” after their overwhelming victory in 2019, when they achieved a vote share of 13.2 percent and became the fourth strongest political party in terms of vote shares. Things have changed, however, and the Greens are the undisputed election losers this year. Nevertheless, the Green Party still demands to be represented in the Federal Council and will attack one of the FDP seats in the upcoming governmental election in December. Indeed, the FDP is clearly overrepresented with two seats in the government. But the SP, too, is overrepresented with two seats and an electoral strength of 18.3 percent. Out of the seven Federal Councillors, six present themselves for re-election. Traditionally, incumbent Federal Councillors have always been re-elected by the Federal Assembly, with only a few rare exceptions.

Alain Berset, the current Swiss president, and Federal Councillor from the Social Democrats is the only one who will leave the government and thus needs to be replaced. The SP is currently in the selection process of candidates and will propose two to three candidates to the Federal Assembly from whom the latter will almost certainly choose someone to replace the outgoing SP Councillor. The Greens have made it clear that they will not attack the vacant SP seat but one of the FDP seats. The chances for them to succeed and enter the government are low. Not only would the left-wing Greens need to persuade a lot of right and centre-right parliamentarians but also many consider the Left as overrepresented with three seats (2 SP and 1 Green). While arithmetically speaking, the Green Party’s demand for a seat in the Federal Council is legitimate, it will probably still take some time – institutional changes in Switzerland are rare and if they happen, they do so slowly. Only when one of the FDP Federal Councillors steps down will the discussion about the magic formula and the appropriate representation of the parties in the government flare up again.

Photo source: https://www.theguardian.com/world/live/2023/oct/19/switzerland-election-populist-swiss-peoples-party-vote-europe-live