By Roderick Pace (University of Malta)

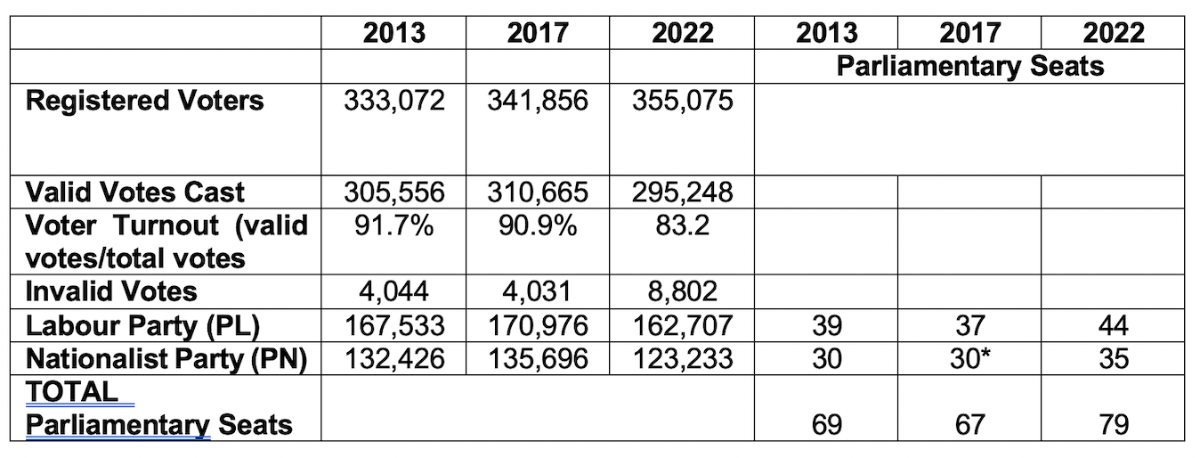

Malta’s Partit Laburista (Labour Party, PL) won a third general election in a row, with a significant margin over its main rival the Partit Nazzjonalista (Nationalist Party, PN). The election was held on the 26 March 2022. Several months before, public opinion polls by national newspapers had consistently predicted the outcome. The 2022 election was characterised by a significant drop in voter turnout, a doubling of invalid ballot sheets and an important increase in the number of women in parliament due to a new ‘gender balancing’ law which went into effect just before the election. As a result, the number of parliamentary seats increased from 67 in the last legislative period to an unprecedented 79. The number of women MPs rose from nine to 23. However, the operation of this law has raised several questions. The election result has been challenged in the constitutional court by Alternattiva Demokratika-Partit Demokratiku (ADPD). The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic did not influence the result.

The decline in voting turnout is significant because Malta has so far experienced one of the highest voter turnouts in the EU. This decline has caught the attention of scholars, but deeper drilling needs to be completed to understand its physiognomy. Is it a sign of voter apathy or antipathy of the electoral system and the party duopoly that has dominated Maltese politics since 1966? Is it a sign that voters are tilting more toward a “great refusal” (Marcuse), opting out of a ‘game’ that is rigged against them?

The Political System

The Maltese political system has often been described as a ‘perfect two-party system’ since only two parties, the PL and the PN have entered parliament in all the 13 national elections held since independence from Britain, the first of which took place in 1966. This trend was disturbed only once, in 2017, when two candidates of the Partit Demokratiku (Democratic Party, PD) entered parliament in coalition with the PN.

Since the 1976 election, Malta and the sister island of Gozo, have been divided into 13 electoral districts (constituencies) roughly of equal size, each electing five MPs. Constitutional amendments adopted in 1987 ensured stricter proportionality between the preference votes won nationally by the parties and parliamentary seats. This meant that the number of seats in parliament could exceed 65 when the majority party (that which polled the majority of first count preference votes but elected less seats than the minority party) was allocated additional seats to give it a parliamentary majority to enable it to govern. In 2007, this principle was extended to the minority party when its share of parliamentary seats fell below the percentage of votes won. This mechanism operates only for parties which manage to enter parliament

For this reason, the size of the parliament has fluctuated since 1987, but the adoption of Act 20 in 2021 to create a ‘gender corrective mechanism’ by allocating 12 extra seats to the under-represented gender, further bloated parliament’s size. The proportion of women in the Maltese parliament has always been very low, hovering around 10% since the 1950s. In 2021 it was a mere 13%, but after the 2022 election it shot up to 29%. Hence the Act has achieved its main objective, but controversies raged after the election about how it can be improved and how it may have discriminated against third parties which did not manage to enter parliament.

The growth of the Maltese parliament has ignited another debate as to whether Malta’s parliament is too big for its population size. The controversial ‘cube root rule’ (Emmanuelle Auriol · Robert J. Gary-Bobo) which attempts to find a satisfactory relationship between the size of parliament and a country’s population would give Malta an 80-seat parliament (cube root of 515,000). But this rule has been challenged on several fronts and I do not think it resolves the issue. For example, Luxembourg’s population of 634.7k would require a parliament of 89 seats, but, it is set at 60. Several other criteria need to be taken into account in determining a parliament’s ideal size and that is why this controversy has fizzled out.

Malta’s Electoral System

The Maltese electoral system is based on the Single Transferable Vote (STV). Party candidates and independents can contest in up to two electoral districts. The candidates’ names are listed in alphabetical order on the ballot sheet. Candidates are grouped according to their party. Voters mark their preferences (1, 2 etc.) on the ballot sheet; they can enter as many preferences as they wish and they are allowed to cross party lines, although few do it. The Electoral Commission registers all persons who are 16 years of age or over in the Electoral Register, which is updated and published periodically. Citizens do not need to register to be included in the register, but there are legal remedies for those who are struck off. Elections are managed by an electoral commission which is nominally independent from government, though it is practically co-managed by individuals who are close to either of the two main parties.

Sixteen-Year-Old Vote

The 2022 election was the first national election in which sixteen-year-old citizens were allowed to vote. The voting age was initially lowered to sixteen for the 2014 local council elections. Legislation approved in 2018 extended it to the European and national elections.

Political Campaigning

Political campaigning is intense: the two main political parties have their own media and share the time on the state-controlled media. Debating time during election campaigns is almost divided between the two main parties. A Public Broadcasting Authority is meant to maintain balance in the reporting and coverage by the media, but both the PL and PN complain of bias in the state media when they are in opposition and are accused of manipulating them when they are in government. In the meantime, small parties and independents complain that they are denied fair state media exposure. The small parties do not have their own radio and television broadcasting channels and can only use the social networks to which the dominant parties also have access. This makes it very difficult for the small parties to get their message across to voters.

Maltese politics is very confrontational and has often been described as “tribal” involving door-to-door campaigning that starts much ahead of the official campaigns. Campaigns are characterised by patronage and clientelism, populist and nationalistic messaging, and pledges aimed at sectoral interests. Around a fortnight before the 2022 election an estimated 580,000 cheques (1.6 times the number of registered voters) covering tax rebates and cost-of-living compensation were mailed to households.

Political parties are regulated by several Maltese laws including a Financing of Political Parties Act (Chapter 544, Laws of Malta). But they have found ways of slipping their harness.

Electoral Programmes

All parties publish electoral programmes outlining what they intend to do if elected. The effect of these programmes on voting intentions is not clear although some of their more noteworthy points are often strongly debated during the campaign. The PN published its programme on 24 February: it featured 540 proposals. Two weeks later the PL replied with its own manifesto containing 1,000 proposals. The new political coalition, a fusion of the green party Alternattiva Demokratika (AD) and the PD (hence ADPD), published its programme in the beginning of March. As would be expected, ADPD based the manifesto on green politics, but tried to free itself from being cast as a single-issue party by emphasizing other issues on governance, the economy, and the fight against organized crime. It also included a lengthy treatment of the controversial issue of abortion, which is banned in Malta, and is debated nationally. It was side stepped in the PL and PN programmes.

Mindful of the green turn in local and world politics, the PL and PN green washed their political programmes. But a careful reading of the manifestos easily uncovers the contradictory concessions that have been promised to various sectors particularly the construction sector which is responsible for the most acute degradation of the urban and rural environment.

The economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic were not very crucial in this election. The government successfully carried out the vaccination programme while the effects of the economic slowdown caused by the pandemic were mitigated by direct transfers to businesses, wage support schemes as well as tax deferrals some of which were disbursed from EU budgetary aid.

As in the previous elections held since 2013, Malta’s role in the EU did not feature in the campaign. Both the PL and PN concur that Malta is “in” although not necessarily “an integral part” of the EU.

* includes two seats won by the PD.

The election result showed clearly that most voters were content to maintain the status quo. Events such as the assassination of the journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia that brought down a PL Prime Minister, allegations of corruption and a culture of impunity, big deficits in the governing institutions and Malta’s ‘grey listing’ by the Financial Action Task Force (lifted since June 22) did not play a significant role in determining the final outcome. Disgruntlement played second fiddle to the need of prolonging the ‘economic life’ of the economy.

Another factor favouring the status quo was that the PN, in opposition since 2013, has not yet rebalanced itself and has not attained the standing of an alternative government. It changed its leader twice since the 2017 election, and it often committed sudden policy U-turns reflecting that policy objectives were not being thoroughly thought out before going public. During the campaign, the PL and PN also resorted to some populist pledges: the most glaring PN proposal was to give traffic offenders a second chance if they do not commit another traffic offence within a period of six months. The party also finds it hard to embrace secularism and is glued to a conservative Catholic morality when its potential support comes from an increasingly heterogeneous electorate. In 2011, it strongly opposed the introduction of divorce but lost the argument. It happened again on LGBTIQ rights, same sex marriage, and it is happening again on the decriminalization of abortion. In July 2022, its parliamentary group split on a vote on new legislation permitting the genetic testing of fertilised embryos for inheritable conditions.

The Aftermath

Following the publication of the election result, ADPD started a constitutional case which is still sub-judice, on the grounds that the law to ensure proportionality and the gender balancing law favour only the two main parties in parliament and discriminate against the smaller parties. In the election ADPD obtained 4,747 or 1.6% of the valid votes cast but failed to enter parliament. With the additional seats in parliament to address proportionality and gender balancing, PL-PN need less votes to fill a parliamentary seat than ADPD.

However, the election results tell another story worthy of scrutiny. The first worrisome point is that the number of women elected in parliament would have been less than in the previous legislature had the gender mechanism not been introduced. This shows that the socio-cultural aspects that are keeping women out of politics needs more than a gender corrective mechanism.

The second point is that although the size of the electorate has been growing, voter participation, defined as the number of valid votes cast as a percentage of the total eligible voters, has been declining steadily. The 2022 election was a watershed: less valid votes were cast than in the previous election despite the growth in the electorate; the number of invalid votes more than doubled; and both the PL and PN received less votes than they did in the previous election.

The 2022 election is a done event but what it had to say to us opens a number of research avenues that would allow us to decipher the whole message.

Photo source: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/3/27/malta-elections-ruling-labour-party-claims-victory