By David Pupovac (Central European University Alumni)

The background of the election

On April 24th, 2016 yet another early parliamentary election took place in Serbia. The ruling coalition, led by Prime Minister Aleksandar Vučić from the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), called for an early election in order address the social conflict which blocks the reforms and to win a full mandate to finish the necessary reforms for EU accession by 2020. However, there is a consensus that the real cause of the early election was the attempt to consolidate, strengthen and prolong SNS’s power at the national, provincial and local levels. In particular, as the parliamentary election coincided with the provincial elections, the SNS had an opportunity to challenge more than a decade and a half-long rule of the Democratic Party (DS) in Serbian province of Vojvodina. In this respect, the SNS sought to capitalize on Vučić’s unprecedented popular support and to form a stable majority which would enable it to govern in the next four years.

The pro-EU opposition went into the elections weakened and disunited. The parliamentary election of May 6th 2012 and, particularly, the subsequent early parliamentary election of March 16th 2014 crushed the opposition and eliminated smaller parties from the National Assembly. SNS’s pro-European stance and the opening of the first EU negotiating chapters left the opposition with no alternative policies. The efforts to form a pre-electoral coalition composed of the DS and some of its numerous splinters (the Liberal Democratic Party – LDP and Social Democratic Party – SDS) were unsuccessful. Moreover, the pro-EU opposition failed to reform and to address the issues which led to its downfall in 2012 and 2014. Rather, it chose to compete with almost intact leadership structures and slightly altered policy agendas.

On the other hand, the pro-Russian/nationalist opposition was predicted to do well. This expectation was predominantly due to the return of the leader of the Serbian Radical Party (SRS), Vojislav Šešelj, from the detention in the International Criminal Tribunal for former Yugoslavia (ICTY). The Democratic Party of Serbia (DSS) and Dveri, which narrowly missed to pass the threshold in the preceding election, formed a coalition which was expected to enter the parliament. In addition, the trend of the increased disillusionment with the EU, uncertain accession prospects, and perpetual tensions with Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the government in Priština created a favorable environment for the nationalist parties.

The campaign and the elections

Despite the high stakes, the election campaign was uneventful. Partially, this may be attributed to SNS’s dominance over the mass media and, particularly, to the evident underrepresentation of opposition parties with respect to the electronic media. However, the failure to win seats in the previous election and the reduction of state granted funds meant that many indebted opposition parties could not compete on par with the parties of the ruling coalition. The parties of the ruling coalition, particularly the SNS and the Serbian Socialist Party (SPS) exploited the advantage of incumbency by increasing their participation at official events during the electoral campaign and by blurring the distinction between state and party activities. Furthermore, the governing parties exerted pressure on voters employed in the public sector to attend their rallies. Opposition parties tended to use negative campaigning directed at the ruling parties rather than focusing on their own programs. Their campaigns were rather uninventive, sometimes populist and focused predominantly on the personality of the Prime Minister. The 2016 election was characterized by the further advancement of the Internet based campaigns, which were particular skillfully used by Dveri/DSS and Dosta je bilo – Enough is enough (DJB) lists. Nevertheless, the lukewarm campaign did not result in the alienation or indifference of the electorate. The turnout was about 56 percent, which is similar to the turnout in the 2012 and 2014 parliamentary elections.

Although the opposition parties challenged the fairness of the election, the election procedures were generally conducted in accordance with the law. Apparently, the major breach of the electoral laws concerned the collection of 10,000 signatures necessary for the lists to enter the ballot. Namely, it was suspected that several lists forged the signatures, while due to a legal technicality, a list managed to enter the ballot despite the credible evidence of forgery. A number of lists applied for national minority status solely to obtain the privileges granted to ethnic minorities. Furthermore, several opposition parties claimed that the election was rigged by the means of carousel voting. However, up to now, there seems to be no evidence of a systematic manipulation.

The results

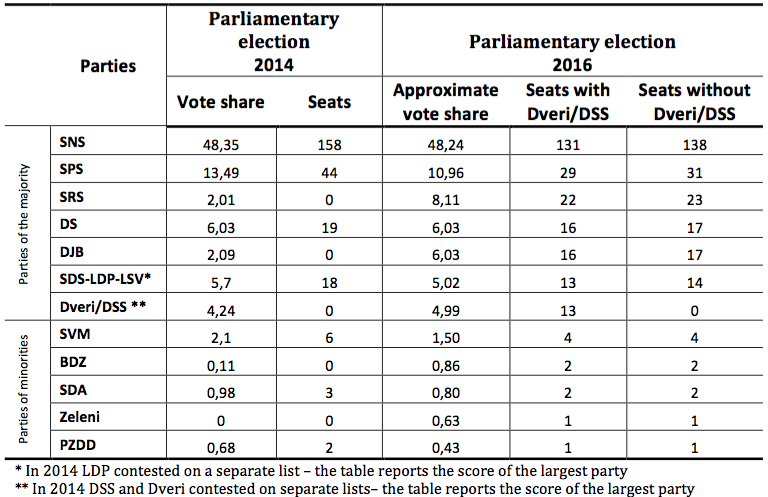

Although all polls forecasted a landslide victory of the list led by the SNS, the results of the election, that is their absence, is what the parliamentary election of 2016 will be remembered by. The controversy involved both independent election observers, who initially made grossly inaccurate predictions of the final results, and the Republic Electoral Commission, which remained silent for most of the election night. While without a doubt this confusion was predominantly caused by the number of lists which succeeded in winning the share of votes close to the 5 percent electoral threshold, the slow dynamic of publishing preliminary results and, particularly, the silence of the Republic Electoral Commission, casted doubts on the fairness of the election. At the time of writing this post, the final composition of the parliament is not known as the joint list of the Democratic Party of Serbia and Dveri (DSS/Dveri) is lacking a single vote to pass the threshold. Consequently, the rerun of the election on 15 polling stations on May 4th 2016 may have major consequences on the composition of the parliament. This controversy brought about a rare unity between pro-Russian and pro-European opposition parties which organized a joint protest against “vote rigging” on Saturday, April 30th 2016.

However, regardless of the final composition of the parliament, the ultimate result of the election is the resounding victory of the SNS. Considering the parliamentary election, the SNS managed to win roughly the same share of votes as it did in the 2014 election. However, due to the number of parties which passed the electoral threshold and D’Hondt allocation rule, SNS’s votes were actually translated into a smaller number of seats in comparison to the composition of the 2014 parliament. Consequently, in order to alter the Constitution (a requirement for further EU accession), the SNS will have to reach a compromise with the opposition. Nevertheless, SNS’s pre-electoral coalition still holds the absolute majority of seats in the National Assembly. Furthermore, the SNS managed to take the power in Vojvodina by winning the absolute majority in the provincial parliament and improved its position in the municipal elections. Consequently, the SNS will have almost complete control over all levels of the government.

After two years of absence, the radical right parties are back in the parliament. Driven by the abrupt return of Vojislav Šešelj from more than a decade long detention in the ICTY and his subsequent acquittal of all charges on March 31st 2016, the SRS is again the most prominent representative of Serbian nationalism. Currently it is the third strongest party in the National Assembly with more than 20 MPs. Furthermore, if the Dveri/DSS list succeeds in passing the electoral threshold, the populist/ultranationalist side of the political spectrum in the parliament will be accompanied by the religious/authoritarian far-right.

Similarly to the recent elections in the region, one of the most striking outcomes of the elections is the strong showing of a newcomer – the association DJB, led by the former Minister of Economy in Vučić’s 2013 government, Saša Radulović. In Serbian politics, where almost all parties participated in the government at some point in time and their leaders are present on the political scene for decades, Radulović is a fresh face. Although most of the electorate is not familiar with the program of the association, the DJB uncompromising critique of Vučić’s government and its outsider image attracted disenchanted and young voters. So much so that party’s electoral result matches the result of the main pro-EU opposition party, the DS.

And indeed, pro-European opposition parties are the greatest losers of the election. Not only that they managed to lose the control of government in Vojvodina and additional seats in the National Assembly but, more importantly, they remain divided, unreformed and incapable of presenting credible policy alternatives to SNS’s platform.

Looking ahead

Regardless of the final results the parliamentary election, the formation of government will be at discretion of the SNS. Given that the SNS announced it will seek a broader consensus for the reforms, it is probable that the future government will incorporate additional partners. In this respect, the most likely candidates are the Socialist Party of Serbia and the United Serbia, which already coalesced with the SNS in 2012 and 2014.

The government will keep its pro-European course while at same time trying to maintain good relationships with China and, particularly, Russia. It can be expected that Vučić will stay on the path of reconciliation with respect to the Yugoslav successor states, including further negations with the government in Priština. Therefore, major changes of course in terms of international relations are unlikely.

However, internally, the new term of Aleksandar Vučić is probable to be more turbulent and the government may face social and/or political unrests. Namely, following the arrangement with the International Monetary Fund, the government introduced austerity measures (cuts in public sectors wages and pensions), which are still to result in the improvement of economic and social conditions. Additional reforms and layoffs are expected in the public sector. However, the unemployment rate in Serbia is already at 20 percent. On the other hand, although government placed a strong emphasis on the fight against corruption, so far there has been no final conviction for high-level corruption. At the same, clientelism and particracy are taking hold in the society, while political parties and media are under ever-growing pressure from the government and its proxies. Coupled with the slow and halfhearted process of EU accession (which is currently blocked by Croatia), these conditions are likely to bring the social discontent to the boiling point. In 2012 the SNS came to power with a mandate to reform the state and improve the economy; in 2016 the patience of the public may start to wear thin.