By Peter Učeň (Policy Analyst)

The recent parliamentary elections in Slovakia took place after the full term of the single-party government by the nominally social democratic Direction – Social Democracy (Smer-SD) party. The legacy of this government as well as the pre-election polls suggested that Smer-SD will defend their dominance with the score somewhere in the mid-thirties. It has also been generally accepted that the ruling party will seek a coalition with either Slovak National Party (SNS) – extra-parliamentary but rising in the polls – or one of the mainstream opposition centre-right parties such as Christian Democratic Movement (KDH) or the interethnic Most – Híd (Bridge) party. The newly created and ambitious Network (#Sieť) centre-right party was to remain a leader of the opposition – solitary or in alliance with KDH and the Bridge – while the two anti-establishment, centre-right parties Freedom and Solidarity (SaS) and Ordinary People and Independent Personalities (OĽaNO), that had entered the parliament in 2010 and 2012 respectively, were believed to face the uphill struggle to pass the threshold. This picture of the events to come has been confirmed by the public opinion polls collecting field data as late as four weeks prior to the election day on March 5. However, during the newly introduced two-week ban on publishing the public opinion polls’ results, the opinion of the voters seem to have changed dramatically to bring about a surprising and for many also highly disturbing shift on the Slovak party-political landscape.

Local pollsters have been observing a trend in the growth of the undecidedness among the voters at least since 2010. Three kinds of undecidedness have been pointed out: the lack of certainty regarding the participation in elections, the uncertainty as to the choice of the preferred party, and the remarkably week firmness of such decision in case of some parties. According some estimates, more than thirty percent of electorate were unsure whether they would show up at the polls at all, or which party to choose, and, importantly, admitted, that they might change their choice in the polling station. During the moratorium the unpublished poll results had been leaked suggesting the decline of the support for Smer-SD, growth of popularity for SaS and OĽaNo, and, most importantly, the possibility for two new contestants to attack the threshold of representation. On March 5 the existing potential for instability materialized in the full force confirming the trends suggested by the leaks in the most dramatic way.

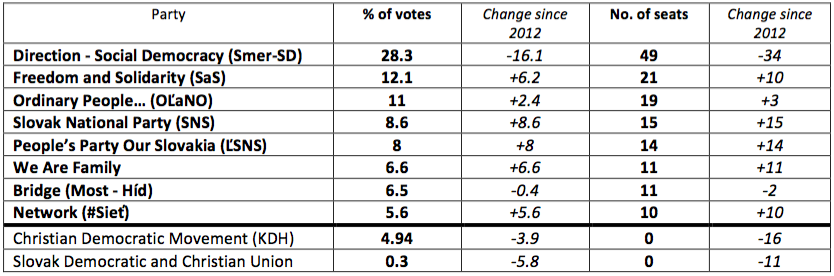

The support for the ruling SMER-SD fell below thirty percent. The two supposedly ailing anti-establishment parties SaS and OĽaNO doubled their projected gains while the assumed leader of the opposition, #Sieť, barely made it to the parliament. The Bridge party’s performance was slightly disappointing as well. (The former dominant right-wing party, Slovak Democratic and Christian Union, SDKÚ, decomposed gradually in the aftermath of the 2012 elections and did not play a role in these elections. Its result suggests that its voters have been taken over by other centre-right parties, namely SaS and #Sieť.) SNS again returned to the parliament – for the second time in the last decade – with the gain matching the projections. But KDH failed the threshold by mere six hundredths of percent and voters elevated to the parliament two new, anti-systemic parties, Kotleba – People’s Party Our Slovakia (ĽSNS) and We Are a Family (Sme rodina). While eight parties will be represented in the new Slovak parliament, due to the changes in support described above, the parliament is effectively hung, and construction of any ruling coalition will be a very precarious process. (Only fragile multi-member coalitions are possible and the only really important question is whether they will include Smer-SD or not.)

Any meaningful explanation of the election results – their reasons and possible consequences – should probably address (1) the fate of the ruling party Smer-SD, (2) the realignment that has taken place among the centre-right opposition, and (3) the entry of the new, anti-systemic contestants into the parliamentary arena.

As for the first issue, the predicament of the SMER-SD could probably best be described by the issue salience and issue ownership-based explanations of electoral competition. Following the outbreak of the mass migration to the EU across its southern and eastern maritime boundaries, Smer-SD adopted a resolute rhetoric demanding the shutting of the permeable boundaries and refusing the obligatory quotas for relocation of the refuges proposed by the European Commission. Prime Minister Robert Fico relentlessly repeated that the government would not allow the mass influx of the refuges to the country or the settlement of a substantial encapsulated Muslim minority on the Slovak territory. The party changed the slogan of their permanent campaign from “We Work for the People” to “We Protect Slovakia.” (While all other parties with the exception of the Bridge in principle agreed with Fico’s stand on the immigration issue, they objected its excessively belligerent manner and the lack of respect for the partners in the EU.) As a consequence, Smer-SD managed to impose the refugee crisis as the dominant salient issue prior to the elections. The party, however, failed to persuade voters about its prominent ownership of the problem. Instead, some of the worried voters turned to the radical right and other anti-immigrant appeals to alleviate their concerns. Moreover, it is widely believed that the saliency of the refugee issue started to vanish some six weeks before the election. It was in part overshadowed by the corruption scandals of the ruling party and the public resentment of the desolate state of public services which itself was often related to the predatory practices of the entrepreneurial groups backed by the ruling party. Teachers’ strike and the hospital nurses leaving their jobs in great numbers shortly before elections gave a poor testament to the state of the welfare state – the loudly declared top priority of Smer-SD’s tenure – and left the ruling party very nervous. Finally, shortly before elections PM Fico resorted to a personal attack on the leader of OĽaNo in which he openly used the confidential information from the tax authorities to discredit the political opponent, leaving an impression of a brutal abuse of the office. As a consequence of these factors, Smer-SD lost some fifteen percent of support and returned to the numbers which roughly define its core electorate and which they can safely rely on provided that Robert Fico remains the leader of the party. As for where the disappointed voters of Smer-SD went, the exit poll suggests that along with abstention, the most logical destinations for them were SNS, ĽSNS and Sme rodina.

When it comes to the unexpected realignment on the right, it has probably took the place among KDH, SaS, OĽaNO and #Sieť parties. (The Bridge’s electoral support is based on the ethnically Magyar voters so it is sociologically distinct. Its main competitor is the smaller Magyar ethnic party SMK.) Pre-election polls indicated some 32-33 percent combined support for the four parties and the actual results matched the projection. What has changed was the expected share of votes among the parties. Before the more detailed data is available, an educated guess is that voters preferred new, anti-establishment right (SaS and OĽaNO) over the traditional right, namely KDH, as they demanded a resolute and consistent criticism of the Smer-SD’s rule and unequivocal refutation of the future coalition with the ruling party. KDH, Bridge, but also new party #Sieť in this respect failed to assure their potential voters that they would not ally with Smer-SD. Moreover, an electoral manifesto of SaS presented an attractive alternative for the floating former SDKÚ members while OĽaNO placed on its ballot a group of the Christian activists in addition to a set of whistleblowers and anti-corruption activists. As the results of the preferential voting suggests, the OĽaNO’s socially conservative candidates did appeal to a part of the KDH electorate. Finally, #Sieť has fallen prey to the last-moment change of heart on the side of unsure centre-right voters as its actual result is just a fragment of what the polls projected. While the party may have impressed in presenting attractive program for the society, it has probably failed where SaS and OĽaNO excelled – in taking up a credible criticism of the ruling SMER-SD and its policies.

Finally, additional two new parties will be sitting in the new Slovak parliament.

ĽSNS is the radical nationalist party with the declared ideology of the radical-right combination of the nativism, authoritarianism, and populism. There are, however few doubts that that party has a cosy attitude to extremist ideas and personalities, and some of their members indulge in anti-democratic notions for the private consumption. Thus, by the standards of the Slovak polity ĽSNS is considered an extremist party as far as its members and their shared convictions is concerned. Their success and popular support, however, should be attributed to the more generic anti-systemic appeal. This appeal shies away from a direct refutation of democracy and in addition to the nationalism it includes cultural conservatism and, more importantly, radical social criticism of the “system.” Under the slogan “With the Courage Against the System” it blames it for the enormous deterioration of the conditions of life for the Slovak nation. This includes not only standards of living but also the denial of decency to the lives of ordinary Slovaks by the ruling class and (numerous) external enemies. It manifests strong anti-corruption and anti-oligarchic drive and proclivities to explanations based on conspiracy theories.

We Are a Family are basically a three months-old protest and political entertainment project based around the colourful personality of its leader, the rich businessman. While the characteristics of its supporters are yet to be discerned, the party defines itself as centre-right, socially conservative and opposing political correctness. The leader Boris Kollár is an anti-elite outrager, but relatively soft-spoken on other issued that corruption of the political class. He and the party share a resolute anti-immigrant stance with the radical right but apart from that has not so far manifested further authoritarian inclinations. Apparently surprised by its own success, the party claims to support any future centre-right government but gives up the ambition to participate in it. While so far the leader seems to be completely happy with all the media attention accompanying the electoral success, it remains to be seen whether the potential for a more aggressive approach represented by some personalities on the list prevails in future.

While different in many respects, the two new participants in the Slovak parliamentary life share a strong anti-political flare. That is one of the main reasons that they were in a remarkable extent supported by the former non-voters, first-time voters, and also by former voters of Smer-SD.

By the way of conclusion, the growing voter undecidedness, namely the proclivity to postpone the choice to the period extremely close to the election day, combined with the long moratorium on publishing the poll results rendered recent elections in Slovakia into an electoral lottery. Many believe that this condition will be a new normal for a time being. This belief also reflects the changes taking place in other aspect defining the voting behaviour of the Slovak voter. Increasingly numerous part of the electorate in these elections demanded clear and unequivocal definitions of the country’s condition as well as equally worded proposals for solutions. The strived for “yes/no” or “good/bad”-type of discourse and refused the mainstream clichés about responsibility, restraint, and impossibility of the simple solutions for complicated problems. Clear and simple solutions were on high demand and the populist stigma de facto ceased to work.