By Peter Učeň (independent researcher, policy analyst, consultant and evaluator) and Oľga Gyárfášová (Comenius University in Bratislava)

Previous general election in Slovakia took place on February 29, 2020. While there is no formal reason to celebrate the recent anniversary, the glance on how the party scene changes during that one year of the “Corona governance” may be worth of a brief reflection: The winner of the 2020 election received almost 25% of the popular vote even though four months before the vote it registered less than 6% of support. Currently, it scores around 10% in party popularity contest which is led by another party which formally did not exist at the time of election. And the popularity scores of the current champion approach those of the election winner a year ago. The first party at issue is the surprising winner on the 2020 contest, Ordinary People and Independent Personalities (OĽaNO). The current most popular party is Voice – Social Democracy (HLAS).

OĽaNO has been present in the Slovak politics since 2010 and since 2012 as a distinct electoral party. Formally a movement, OĽaNO is an anti-party – an electoral vehicle – as well as a radical anti-establishment challenger which puts a particular emphasis on moralistic anti-corruption appeals. In 2016 it obtained around 11% of vote. In October 2019 it was generally considered a struggling party hovering slightly above the 5% threshold of representation. Yet, in four moths OĽaNO managed to quadruple its support. Elsewhere we describe the appeals it used in the campaign. As a corollary, OĽaNO was practically the only party whose campaign fully aligned with the dominant emotion of 2020 elections – the resentment of corruption and “mafianization” of the state structures (particularly police and judiciary) by the ruling parties. This fact, along with the nature of the voter-party relationships addressed later in this blog made its miraculous rise possible.

HLAS has been created in summer 2020 as a splinter from the former ruling and a long-time pivotal party of the Slovak party system, Direction – Social Democracy (Smer-SD) with more than two decades of history of shaping Slovak politics. It was conceived by a part of the Smer-SD leadership around former Prime Minister Peter Pellegrini. This faction realized that further continuation of coexistence with the faction around party founder and Pellegrini’s predecessor in the prime ministerial post, Robert Fico, was harmful to the prospect of their further operation in Slovak politics. HLAS marketed itself as purifier of the original Smer-SD’s social-democratic mission. The rump Smer-SD has been also vehemently declaring the ownership of the social-democratic trademark but in the meantime, it was transformed by Fico into a radical sect pursuing supporters in the ranks of the anti-systemic voters entertaining various conspiracy theories to which Fico actively contributed.

The conflict within the most successful party in the Slovak post-1989 history has been the result of the spillover from the investigation of the 2018 murder of the investigative journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée Martina Kušnírová. The public pressure on effective and unhindered investigation resulted in findings which surprised even the seasoned cynics among the observers and commentariat. It turned out that as it has been long suspected, under the auspices of Smer-SD a system has been groomed that systematically enabled a group of people (oligarchs, their henchman and allies within state institutions) to enjoy selective access to justice and exclusive information from police investigation regarding themselves and others. It also provided them protection from investigation provided by the top prosecutorial offices in case their dubious business practices were exposed. In short, the access to this system has become the indispensable part of the business model for the participating businesses and in exchange they provided compensation to the top politicians of the ruling party Smer-SD. Kuciak’s murder has become to be generally considered a consequence of the atmosphere of impunity among these groups – nicknamed “our people” – and an act of silencing Kuciak who came up with novel ways of collecting and interpreting open data which disclosed many aspects of the nefarious business dealings of “our people”.

Prime Minister Fico – while never admitting the moral co-responsibility or involvement of people around him – resigned shortly after the murder to offset the public anger and the party replaced him with popular Pellegrini. Over time, the two factions drifted away over the question of political strategy (rather than ideology or a programme). Fico’s efforts were focused on the denial of involvement or responsibility of his group in the corrupt system of exchanges. This was accompanied by suggestions that the course of events was the result of the conspiracy against his lawful government by nefarious foreign and domestic forces (including George Soros).

As for the Pellegrini’s faction, they correctly considered themselves much less vulnerable to investigations. Therefore, they hoped for continuing their operation on the Slovak party scene as relatively consensual actor with the coalition potential and the prospect for participation in future governments. Following the replacement of Smer-SD as the pivotal party in 2020 elections, Pellegrini’s faction emancipated themselves from Fico and created the new party. HLAS has soon become to dominate popularity polls thus not only besting the mother party, Smer-SD, but also OĽaNO. This process has unfolded against the backdrop of the erratic and often politically embarrassing performance of the new government, particularly OĽaNO’s inner group around Prime Minister Igor Matovič. But the abrupt changes taking place within the system should not be entirely attributed to the vicissitudes of the Corona governance. Instead, they are the consequence of a few features of the party competition in contemporary Slovakia we have been observing some time now. They are related to the fluidity of voter preferences, the lack of party identification as well as the pragmatism of parties’ appeals.

Voters in motion

A high volatility of partisan support has become a sort of cliché in scholarship about post-communist party system. This cliché is, however, well substantiated by the data. Slovakia is no exception from the trend.

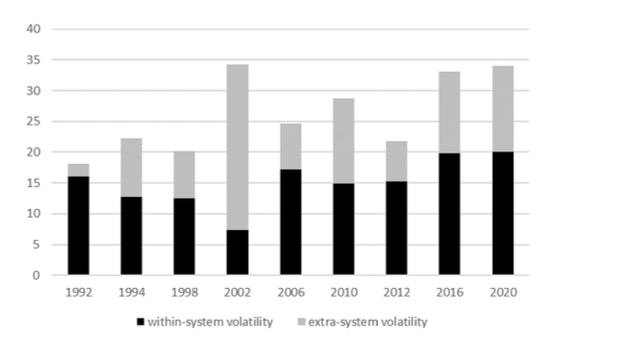

Figure 1: Party system volatility in Slovakia, 1992–2020 (Pedersen index)

Source: Linek – Gyárfášová, 2020. Official electoral results, authors’ own calculations.

Note:Calculations are based on the combined votes method, which in particular means that the estimates are conservative: if a stricter approach towards organizational continuity of parties were used, net volatility would be even higher.

for three decades of democratic experience The aggregated volatility has been showing the trend of a gradual increase. In the 2020 election it has reached about the same level as in 2002 one which was characterized by so far biggest breakthrough of the new political parties into the national parliament. At the level of individual volatility, based on the 2012, 2016 and 2020 exit poll data, we see that the average share of loyal voters who repeat their choice in two consecutive elections decreased from 62 percent in 2012 to 46 percent in 2020 – of course with high variance among individual parties.

In 2020 no relevant political party had core of loyal voters higher that 65 percent and for some parties the share of stable voters has fallen below one third.

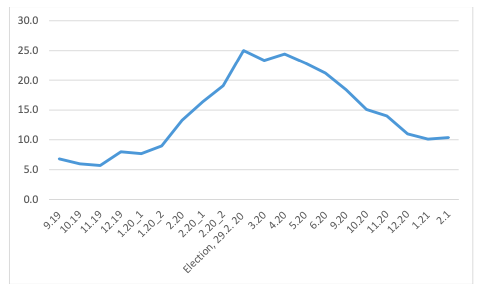

As previously mentioned, the recent champion of the fluid support has been OĽaNO. Within a year its support quadrupled and then consecutively halved.

Figure 2: Dynamics of support for the OľaNO movement

Source: FOCUS agency ( https://www.focus-research.sk/?section=show&id=10)

The possible explanation of the movement’s steady drop in popularity is intimately linked to the reasons why they won in the first place. In addition to its core support, in early 2020 OĽaNO managed last-moment mobilization of a substantial part of voters who were previously non-voters (this also applies to the first-time voters). It also succeeded in attracting the many from among those who were undecided – previously voting other parties – and postponed their voting division to the last moment. Their primary reason for switching was movement’s prominent ownership of the anti-corruption issue. (Around 69% of OĽaNO voters declared in the 2020 exit poll that the decisive reason for vote was movement’s anti-corruption drive.) Easy come, easy go – a part of these two groups quickly denied a continued support to OĽaNO vis-a-vis its government performance. HLAS has been just one successful hunter of these voters – others deserted to OĽaNO’s coalition partners, namely Freedom and Solidarity (SaS) party.

Timing of voting decision

Another important finding is that in the last decade growing segment of voters in Slovakia has been postponing their voting decisions to periods closer – or even extremely close – to the act of voting. Pollsters have been seeing at least this since 2012 election. Also, the 2020 exit poll results suggested that 14% of voters made their choice only on the election day and other 15% during the last week before it.

Turnout increased in about six percentage points to 66% which is a lot by the Slovak standards on 21st century, so Slovak voters apparently intended to make a point in 2020 elections.

It is widely supposed – though almost impossible to substantiate by the data – that the part of electorate (certainly big enough to tip the result of elections) is engaged in a cycle which includes mobilisation by the new party contender followed by the disappointment and retirement among the non-voters. Such withdrawal is, however, temporary and these voters are clearly available for consecutive re-mobilisation should the appropriate champion appear.

Base of the voting decision

At the risk of sounding casual or anecdotal, it could be claimed that party identification does not play particularly important role when it comes to the ties between parties and voters. It is not valued by voters but it also seems that parties themselves are somewhat sceptical regarding the usefulness and viability of efforts towards achieving lasting party identification with a substantial group of voters.

Instead, we see the trend among voters towards elections as “supermarket of parties” from which the choice is made just shortly before the consumption and it is based on the need to satisfy the pressing concern rather than to confirm lasting loyalty to a party. Except for sociological and cognitive factors, the important reason seems to be the lack of trust towards party politics among the constituency. Thus, any effort to build a lasting partisan identification may be seen by electorate as vain given the extremely high probability of being disappointed. Hence the “supermarket” and willingness to switch or temporary withdraw among the non-voters (and being eventually mobilized by the new champion or appeal in future).

As for the parties, the impression is that they increasingly accept this sociological trend and adjust their strategies accordingly. Some parties keep paying lip service to the virtues of party identification more than others but message from the fate of the gradually declining “PID parties” in the short history of party system has been clearly received. OĽaNO has been absolutely excelling in reinventing its appeal in each consecutive election and combining the very low personnel continuity with remarkable endurance of the credible anti-establishment posture. But as the story of OĽaNO also suggests, unanchored voters mobilised at the last moment seem to be unreliable and ephemeral source of support.

Conclusions

Given the mentioned trends have been observed for a notable period of time, we should assume that their causes are reasonably rooted. Therefore, we should admit that the story of the skyrocketing increase of support for the party few weeks prior to elections could be in future occurring more frequently than we dare to admit. Accordingly, parties may be motivated to put most of their efforts to short and intense campaign bursts at the expense of the work with voter between elections. The search for the paramount emotion or issue capable of moving a part of the available electorate to their ranks may become parties’ primary concern. Voters – or at least their part – will expect such behaviour and make themselves available to the walk through the supermarket of parties. In a similar vein, we can expect the electoral advantage for parties which put emphasis on responsive opposed to those which place the responsibility at the heart of their appeals.

The search for the stability in terms of party identification within the Slovak party system may thus not only be mission impossible, but also the undesirable outcome (mission avoided).

Photo source: https://korzar.sme.sk/c/22392940/matovic-nech-si-pozrie-grafy-pre-volicov-kollara-je-lepsi-pellegrini.html