By Ingrid van Biezen (University of Leiden)

Liberal parties on the rise

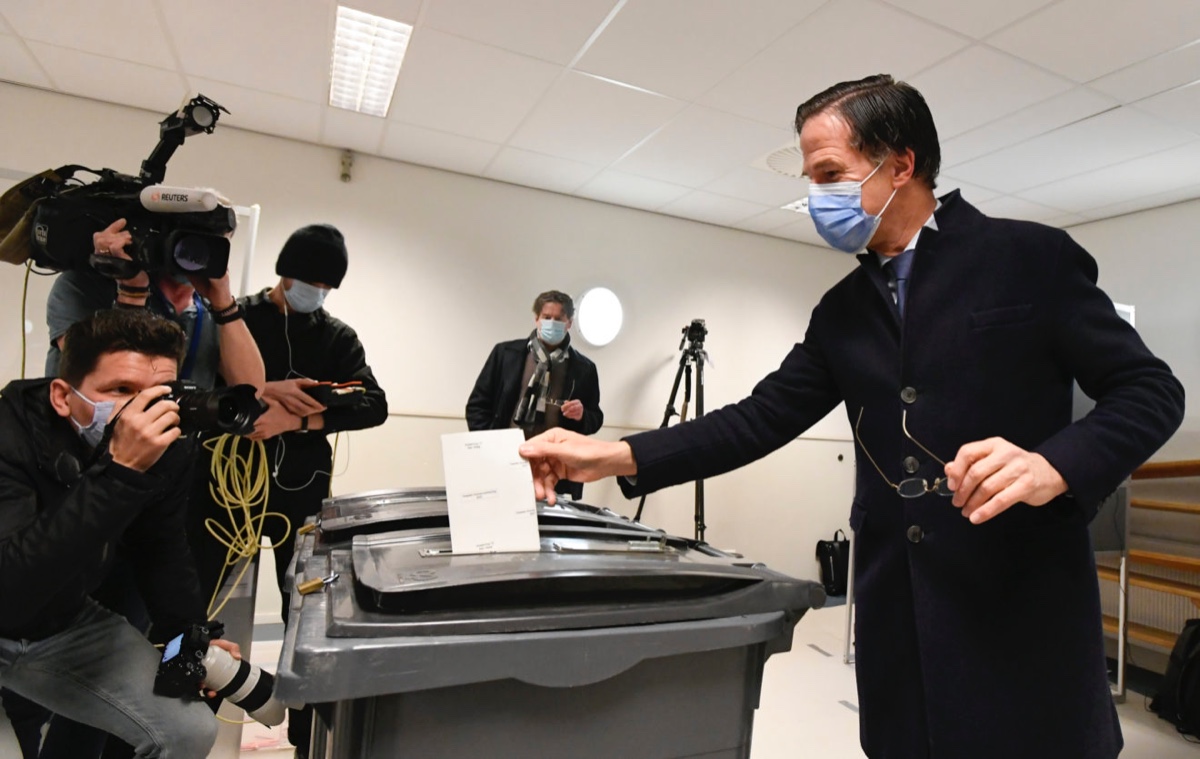

After a tame and uninspiring campaign, Prime Minister Mark Rutte led his party (VVD) to win the Dutch elections for the fourth time in a row. With over 88 per cent of the vote counted,* the liberal-conservatives look to obtain 36 seats (out of a total of 150), gaining 3 seats compared to 2017. Turnout was up slightly up, from 81.6 to 82.6 per cent, apparently not affected by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The VVD victory had been widely anticipated; the party had been comfortably and consistently leading the polls for over a year. As the largest party, the VVD will again take the lead in the formation of a new government. A fourth government under his leadership will allow Rutte to break the record of the longest serving Prime Minister, currently held by Ruud Lubbers (CDA) who served a total of 4,309 days in the 1980s.

Tensions within the 4-party coalition had become increasingly visible in the months before the elections, while there is no shortage of political controversies and scandals. Indeed, the next government will have to crack a number of tough nuts, from climate change to the labour and housing markets, and will face at least two parliamentary inquiries, one over the welfare scandal (see below) and one over the winning of gas in the northern province of Groningen (and possible a third over COVID-19). The campaign was quiet and subdued, however, perhaps because of the ongoing pandemic, perhaps because the outcome was a foregone conclusion and all parties are aware that they cannot afford to distance themselves too much from the VVD if they aspire to be credible coalition partners.

This was also a caretaker government, as a result of which most hot topics were off the agenda and technical issues around the handling of the pandemic prevailed. The government had collectively resigned in January over a major scandal involving tens of thousands of citizens wrongly accused of welfare fraud, plunging them into massive debts or facing eviction from their homes over sometimes minor offenses such as a missing signature. Many of those affected came from migration backgrounds; the tax office eventually admitted to systematic ethnic profiling. A parliamentary committee concluded that the state, with many parties having enthusiastically jumped on the right-wing ‘law and order’ bandwagon, had been responsible for ‘unprecedented injustice’ against its own citizens for nearly a decade.

In many ways, the collective resignation was an act of self-preservation by the government. This way Rutte avoided a fundamental debate with parliament over the issue as well as the looming prospect of losing a vote of no-confidence. In the end, only the Minister of Economic Affairs Eric Wiebes (VVD) and PvdA leader Lodewijk Asscher, Minister of Social Affairs at the time of the welfare scandal, took responsibility and left the political scene over the affair. The scandal did not seem to have much of an electoral impact.

The major surprise on election night was the excellent result for the social-liberal party D66, one of the four coalition parties. After a slow start, and having initially been derided for her ambitions, the new party leader Sigrid Kaag successfully presented herself as an alternative for the position of Prime Minister, criticizing the endemic sexism and misogyny in Dutch politics and society in the process. Rising to 24 seats, D66 not only paralleled its best result ever, it also countered the trend by which it tends to be penalized for participating in government coalitions. D66 appears to have successfully mobilized a part of the undecided electorate and, although it is too early to say anything conclusive about the direction of voter swings, to have drawn large numbers of voters away from the parties of the left, whose performance was much less successful than predicted shortly before the elections.

A further blow to the left

Although progressive issues (climate, animals, Europe, income inequality, housing shortage, a stronger state, less market) were rather in vogue in the manifestoes of many parties, left-wing parties are the clear losers of the elections. PvdA, GroenLinks and SP together obtained only 25 seats. The Social Democrats (PvdA) remained stable at 9 seats, unable to recover even marginally from its historical defeat four years earlier, when it had plummeted to this record low from 38 seats. It probably did not help that party leader Asscher had decided to step down two months earlier over the aftermath of the welfare scandal. Even though his successor Lilianne Ploumen has the necessary political expertise as a former chair of the party and former minister for Foreign Trade and Development, she as yet lacks Asscher’s name recognition and popularity.

The results for the Socialist Party (SP) and green left (GroenLinks) were devastating. The SP went down from 14 to 8 seats; GroenLinks was reduced by half and maintained only 7 of its original 14 seats. The animal rights party PvdD obtained an additional seat to arrive at a total of 6. Ethnic party DENK, a split-off from the PvdA with a focus on (mostly Turkish) immigrants, lost one of its 3 seats. The message that GroenLinks aimed to convey during the campaign as the driving force for a possible fusion of parties on the left – the party even included the names of the leaders of D66, SP, and PvdA on its posters – fell completely flat. SP voters in turn may have been deterred over the attempt to present the former activist party as a credible coalition partner. This strategy also contributed to a rupture with its own youth organization ROOD, as the party accused some board members of the youth organization of being radical communists and ROOD criticized the mother party in turn for the suffocating culture in which deviant voices are being suppressed. The SP did not benefit electorally from its role in bringing the welfare scandal onto the political agenda, in which MP Renske Leijten worked closely together with Pieter Omtzigt (CDA).

Christian Democrats in decline

Results for the CDA were equally devastating. Losing 4 of its 19 seats, the Christian Democrats today are a mere shadow of their former predominance in Dutch politics. The party suffered from the relative newness of its leader, Finance Minister Wopke Hoekstra, as well as internal turmoil in the run-up to the elections. The primaries – in which Health Minister Hugo de Jonge very narrowly defeated thorn-in-the-side of the party Pieter Omtzigt – had been chaotic and unsettled. The obvious candidate Hoekstra had unexpectedly decided not to run, the digital selection process was marred with problems (with Omtzigt’s wife notably receiving a confirmation of her vote for De Jonge), and De Jonge eventually withdrew anyway because of his inability to combine the position with his responsibilities as Health Minister during the COVID pandemic, thus making way for Hoekstra. In the end, the new party leader did not do well in television debates, blundered by going ice skating on a rink that had been closed to the public for months because of the pandemic, and did not succeed in uniting the different factions within the party.

The other two confessional parties, the centrist governing party CU and the anti-systemic orthodox-protestant SGP remained stable at 5 and 3 seats respectively.

Increase of the far right

The Freedom Party (PVV) obtained 17 seats, losing 3 seats compared to 2017. It had to relegate its position as the second largest party in parliament to D66. Further on the extreme right, Forum voor Democratie (FVD) quadrupled from 2 to 8 seats. Nevertheless, the result was somewhat of a disappointment for the party as it had dreamed, on the back of becoming the second largest party statewide in the 2019 provincial elections and on the wave of favourable opinion polls, of replacing the PVV as the largest party on the radical right. Also here, internal squabbles abound. The party imploded when it emerged that racist, anti-semitic and homophobic ideas proliferated within its youth organization JFVD. Party leader Thierry Baudet refused to distance himself from the unsavory messages, having in fact made similar contributions according to his former second-in-command Theo Hiddema, and from his protégé and controversial JFVD chair Freek Jansen in particular. After some to-ing and fro-ing within the party executive and parliamentary fraction, Baudet re-asserted his leadership of the FVD while large swathes of public office holders abandoned the party, leaving it severely damaged in the First Chamber as well as at the provincial level.

JA21 emerged with 3 seats, having seceded from FVD because of its ethno-fascist (dis)course, although it is firmly positioned on the radical right. Because it emerged from within the ranks of FVD, it can already count on a substantial representation in the First Chamber (8 seats) and for that reason considers itself a force to be reckoned with. Despite the small loss for the PVV, the radical right further consolidated its position. Taken together, PVV, FVD and JA21 hold 28 seats (against 22 for PVV and FVD in 2017). Combined with other parties located on the cultural right of the political spectrum, moreover, this election has enlarged the parliamentary platform for anti-immigrant, anti-climate, anti-lgtb and anti-Europe voices.

Further fragmentation

Another three new parties entered parliament, bringing the total of newcomers to an unprecedented four. Together they obtained 9 seats. BBB (BoerBurgerBeweging), with 1 seat, focuses on the interests of farmers and the countryside. Bij1 (1 seat) is based on radical equality and economic justice, and is led by former radio and TV show host turned anti-discrimination activist Sylvana Simons. Volt (3 seats) is a pan-European political movement that operates cross-nationally on a pro-European platform.

The Dutch parliament has thus evidently become further fragmented. An unprecedented number of 37 parties competed at the elections this time. According to the prognosis, a total of 17 parties will enter parliament, the highest number since 1918. Four of those are newcomers. There are now 13 parties with less than 10 seats, 8 out of which have 5 seats or less. Indeed, parliamentary fragmentation has more than doubled since the 1980s, when the effective number of parties hovered around 4, rising to 8.2 in 2021 (7.2 according to Golosov’s (2010) measure, in which the share of largest party weighs more heavily).

The high level of fragmentation and polarization, in particular on the cosmopolitan-nationalist divide, makes the formation of government coalitions increasingly difficult. In 2017, it took almost 9 months to forge the unlikely 4-party coalition of conservatives, liberals, and Christian democrats. This time round, the coalition alternatives look similarly limited and the process even more challenging. Because the coalition as a whole has increased its number of seats, a continuation in its present configuration would count on a reasonably comfortable majority. D66, however, is likely to clash with the confessional parties over medical-ethical issues such as euthanasia and abortion. The party was furious, for example, over CU’s proposal to roll back on women’s rights and enforce a compulsory ‘reflection period’ prior to abortion for women who are rape victims. The VVD in turn is likely to be less keen on substituting CU for the left-wing combination of GroenLinks+PvdA – who have indicated they will only join together in any coalition – to form a surplus majority. But with the parties of the extreme right excluded as feasible governing parties, the VVD has few other alternatives than its current government partners.

If they are interested in governing at all, coalition partners will be looking to maintain their individual profile vis-à-vis the predominant VVD. D66 in particular will be seeking to cash in on its victory and focus on its ambition to make the country ‘more progressive, fairer, and greener’. Despite a comfortable majority for the right as a whole, this would tilt government policy somewhat to the left, although the freedom to maneuver for D66 is limited by its dependence on the VVD to form a government. There is no feasible majority to forge a minimum winning coalition on the centre-left.

Since the onset of ‘ontzuiling’ or depillarization, electoral volatility continues to be high in what once was one of the most stable party systems in Western Europe (cf. Mair 2008). In 2017 volatility amounted to almost 25 per cent, indicating that around a quarter of the electorate switched party allegiance, contributing to the near collapse of the Social Democrats. In 2021, despite increased fragmentation, volatility dropped to 13.5 per cent, approximating levels of the turbulent 1970s. In terms of the formation of the party system, like in 2017 we see a cluster of parties in the middle, on the centre-left and centre-right, facing an increased opposition of parties located towards the extremes, some of which, in particular on the right, is anti-systemic. With a few exceptions, the majority of the smaller and newcomer parties have no real coalition potential. On their own, they do not have much blackmail power either, but together they hold roughly a quarter of the seats, reflecting the kaleidoscope of dissatisfaction underneath Mark Rutte’s seemingly comfortable victory.

So far, the Prime Minister’s dominant strategy has been what has become known as the ‘Rutte doctrine’, i.e. that internal discussion with and between civil servants and politicians are not shared with parliament or the public. One of the strengths of ‘teflon Mark’, furthermore, is that he persuasively presents himself as a skillful manager above all parties and successfully diverts responsibility to others, even for problems that have festered for years under his leadership and remain unresolved. But with a host of contentious issues on the horizon, and at least two parliamentary inquiries looming, it is all but certain that Rutte’s usual modus operandi is winning formula for his fourth government. Hence, even though he has indicated that he has enough energy for another 10 years, it is not unlikely that he will choose to depart from Dutch politics – perhaps to continue his career in the EU – once he can go down in history as the longest-serving Dutch Prime Minister ever.

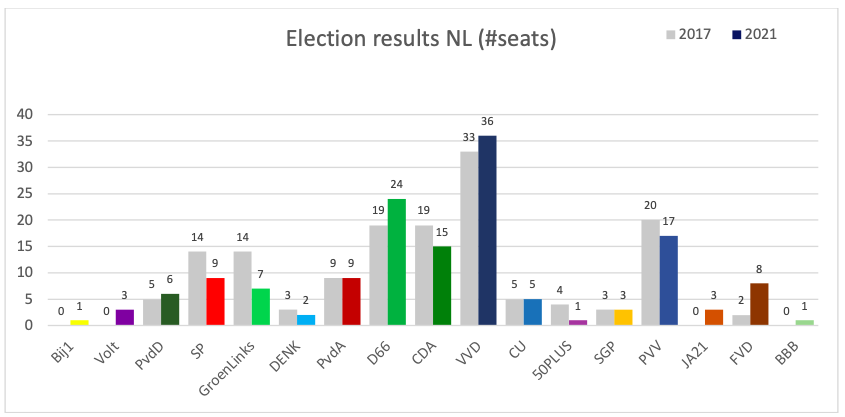

Figure. Electoral results in the Netherlands – number of seats (2017-2021)

Note: provisional results, with over 88 per cent of the vote counted.

* Numbers of seats and percentages of votes are based on the latest prognosis available on 18 March and may differ slightly from the final results.

Note: I am grateful to Ishmael van Biezen-Poldervaart for his feedback.

Photo source: https://www.politico.eu/article/4-dutch-general-election-takeaways-mark-rutte/