By Gorana Mišić (Central European University)

It is old news that the first coalition between HDZ (Croatian Democratic Union) and MOST (Bridge of Independent Lists) fell apart over the conflict of interest of the first deputy PM and HDZ President Tomislav Karamarko in June 2016 – after only six months in power. New elections in September did not bring many novelties: the new HDZ President, Andrej Plenković, the old HDZ, nothing new with MOST – and a new-old coalition was formed. MOST seems to have acquired the modus operandi of playing the role of opposition within the government – something that works for some six months, until they “discover” a major scandal, which forces them out of the government. As the saying goes: Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me. And the shame is not on HDZ, they played it well this time. While Orešković’s government fell after MOST stepped out last year, Plenković’s government kicked MOST out⎯and survived⎯with some unexpected re-shuffling.

A year ago the scandal was about Karamarko’s conflict of interest in the case of selling the national oil company INA; this time it is about saving the indebted Agrokor Group⎯the largest privately owned company in Croatia⎯with a side-plot of the current Finance Minister’s conflict of interest in the story. Agrokor, owned by Ivica Todorić, is engaged mostly in retail, food and agriculture. It is the 11th largest company in Central Europe, which employs some 60,000 people in Croatia (49%), Slovenia (20%), Serbia (19%), Bosnia and Herzegovina (9%), as well as Hungary, Macedonia and Montenegro (3%). According to their reports, Agrokor has 1,912 stores in the region, with 1.5 million buyers per day. Over the years, the Group acquired many large Croatian (Konzum, Zvijezda, Belje, Ledo…), but also some Serbian (Frikom), Hungarian (Fonyódi) and Bosnian (Kiseljak) companies, as well as the biggest retail chain in Slovenia, Mercator. As such, Agrokor has a strong influence on the Croatian GDP and market and economy as a whole. In the words of some Croatian politicians: when Agrokor sneezes, the whole country gets sick. Political elite even more so, it seems. It is not without a reason that Todorić is also known as “The Boss”.

To put the long story short(er): it has long been a public secret that Agrokor does not pay their suppliers and creditors, that their financial reports are close to fiction, and that buying the Slovenian Mercator was one purchase too many. By September 2016, Agrokor accumulated €5.7bn of debt, equalling six times its equity. Agrokor is also very closely tied to politics: not only did Todorić build Agrokor during the 1990s privatisation era, based on the ties between business and politics that ensured him a privileged position on the domestic market, but a number of former Agrokor employees now assume high-level political positons. One of them is the current Finance Minister Zdravko Marić, who used to be Agrokor’s Executive Director for Strategy and Capital. After the debt situation became publicly known, the Government proposed the so-called ‘Lex Agrokor’ in early April, regulating bankruptcy protection for systemic enterprises to save the Group. The terms of bailout for the Group became a matter of dispute, while at the same time the issue of conflict of interest of Minister Marić came up. The HDZ-MOST coalition fell apart over the motion of no confidence to the Finance Minister initiated by the largest opposition party, SDP (Social Democratic Party) and supported by MOST (and, at that time, also HNS – Croatian People’s Party – Liberal Democrats) later in April. SDP based their motion on the involvement of Marić in financial reporting while he was working for Agrokor, but also on his participation in the decision-making (as well as the lack of it) in Agrokor case as a minister. Finally, by the end of April, after MOST ministers had failed to support HDZ’s Finance Minister, PM Plenković dismissed them, effectively expelling MOST from the government. Moreover, with the support of HNS and the regional IDS (Istrian Democratic Parliament), HDZ collected enough signatures in the Parliament to express no confidence to Božo Petrov, the Speaker of the Parliament and the leader of MOST. Under these circumstances, in early May, Petrov resigned and MOST was officially eliminated. However, the government survived – as one part of HNS deserted the coalition with SDP after the local elections in early June and joined the government. The game of power versus ideology (or any ethical principles for that matter), finally resulted in a reshuffled majority, a renewed government, and one new political party – GLAS – emerging from the outcasts from HNS who disagreed with the coalition with HDZ.

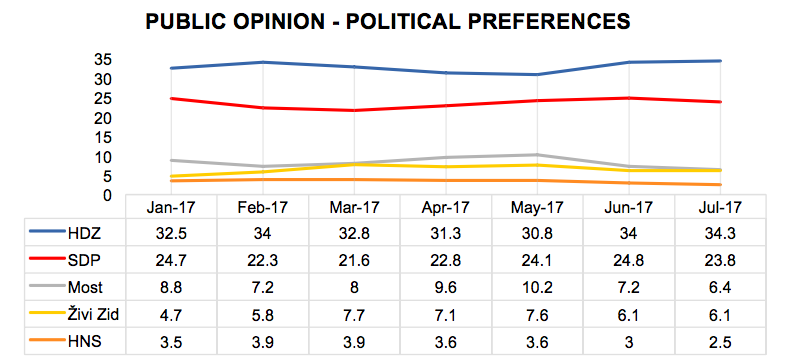

In this soap opera of Croatian party politics, considering the public opinion, the question remains why Plenković did not opt for a snap election instead of reshuffling. With generally inexperienced (especially when it comes to communication with the public) and non-charismatic Davor Bernardić as its new party leader (additionally burdened with his low authority within the party), SDP was never weaker. New election would have thus probably meant more apathy and even lower turnout of SDP voters than during the last election. Regardless of their populist moves, including filing criminal charges against Agrokor owner Todorić (interestingly, the charges were filed by Božo Petrov as a private person, not in his official capacity as the Speaker of the Parliament), MOST showed itself to be a cause of instability, which has also reflected in their ratings. In the light of favourable public opinion and good results in recent local elections, the explanations given by Plenković for not insisting on going to the polls remain rather unconvincing: the need for political and institutional stability, as well as high election costs.

Source: Crodemoskop

Even more surprising and baffling is the move of HNS, which is often referred to as the ‘statistical error party’; a small liberal party which suffered a relatively recent split (in 2014), and whose support usually revolves around 3%. Regardless of its low popularity, HNS has always managed to have a rather high number of mandates: around 10 in times of SDP-led governments. In comparison, for double as high support, Živi Zid currently has eight mandates. Put differently, without being on SDP list/coalition, in good times HNS would have a maximum of half as many mandates, and these will in the future likely be split between HNS and the newly founded GLAS. Deserting SDP in this way makes future cooperation between HNS and SDP difficult to imagine, and whether HDZ will ‘take’ or need them in the future is left to be seen.

Interestingly, HNS describes their beginnings in 1990s as a clear opposition to HDZ: “As the only political party with a carefully developed economic program, HNS heavily criticised HDZ’s economic policy, warning about the catastrophe that HDZ’s privatization model will bring, and because of this, as the time has shown, fully justified criticism, HNS was attacked from all sides throughout the 1990s”. Ironically, they have now united with HDZ over exactly one of those privatisation cases, which has indeed proven to be catastrophic. Their reasoning for this move lies in political and economic stability and putting the people before political interests and ideology.

Are snap elections still an option? Possibly, in the case of major disagreements – and the prospects are high. HNS and HDZ could not be more different on all policy issues that have recently been dominating the public sphere: banning abortion, LGBT rights, education reform, relationship with the Church, civil society, to name but a few. However, HNS has no leverage: they (should) know they have not only lost the credibility, but have also dispersed their voters. This might be their last chance to be a part of a government – and probably the parliament too. Thus, the majority will most likely remain stable.

Acknowledgements: The author is grateful to Nassim Abi Ghanem, Tamara Kolarić and Saša Šegrt for their comments.

Photo source: http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/croatian-government-names-agrokor-extraordinary-manager-04-10-2017