By Ólafur Th. Hardarson (University of Iceland)

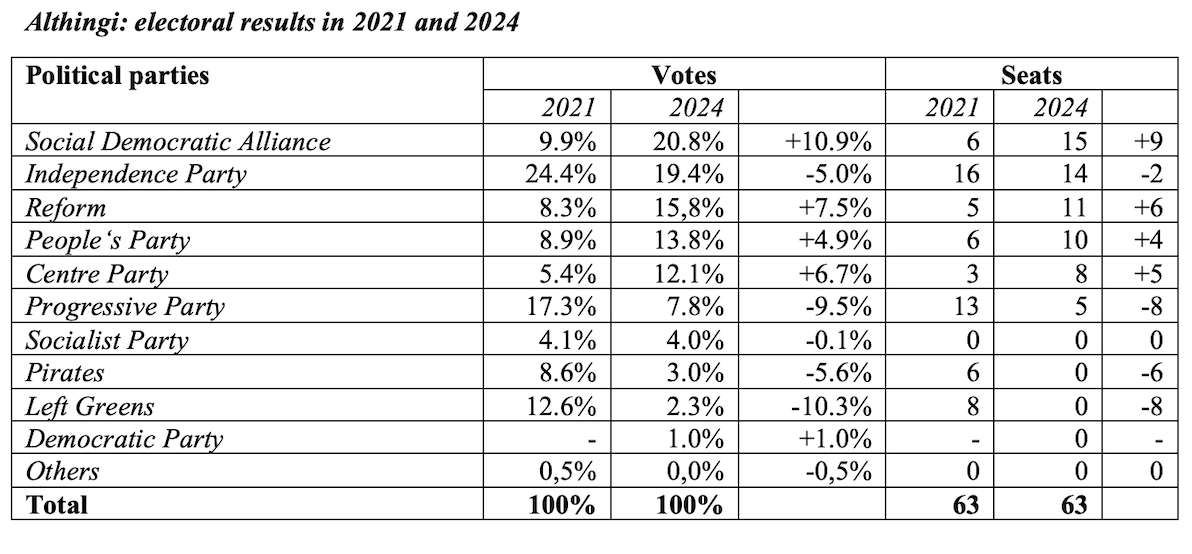

Parliamentary election took place in Iceland last Saturday, November 30th 2024. The government coalition – which had been in power since 2017, lost its majority with a big bang. In 2021, the governing parties, the left-socialist Left Greens, the conservative Independence Party and the centre-right Progressive Party obtained 37 out of 63 seats in the Althingi. Now they jointly obtained only 19 – losing 18 seats. One of the government parties, the Left Greens, lost all its eight seats – which means that for the first time since 1937 no left-socialist party is represented in parliament. The Left Greens lost 10.3%, the Progressive Party lost 9.5%, and the Independence Party lost 5.0%. All three government parties had their worst result since their foundation. Four opposition parties gained votes – the Social Democratic Alliance (+10,3%), the liberal Reform Party (+7.5%), the the right-wing populist Centre Party (+6.7%) and the centre-left People‘s Party (+4.9%). The left-of-centre Pirates lost 5.6% and had no members elected for the first time since 2013 – the Pirates and the Women‘s Alliance (1983-1999) are the only ones of many short-lived „new“ parties in Iceland since the 1970s to survive four electoral terms. The new Socialist Party – considered by voters to be further to the left than any other party – failed for the second time to reach the 5% threshold for adjustment seats. Now its share was 4.0% compared to 4.1% in its first attempt in 2021.

For decades, the traditional „old“ four (Independence Party, Progressive Party, social democrats, left socialists) usually obtained 90-100% of the votes. In 2009, the total share of the old four was still 90% – going down to 75% in 2013, and around two-thirds of the votes in 2016, 2017 and 2021. Now their total share was down to 50% – and one of the traditional four disappeared from parliament for the first time in almost 90 years.

The broad coalition of left and right 2017-2024

The outgoing government was formed in 2017 – and was a highly unusal one, including both the parliamentary party furthest to the right, the conservative Independence Party, and the party furthest to the left, the left-socialist Left Green Movement. Katrín Jakobsdóttir became the first left-socialist prime minister in Iceland – and the only one in 70 years to hold such an office in the Nordic countries.

In 2017, Icelandic politics had been turbulent since the 2008 crash. The only government serving a full four-year term was the left-wing government of the Social Democratic Alliance and the Left Greens 2009-2013 – and that government was a minority government for its last months, due to several MPs abandoning the Left Greens. The coalition of the Progressive Party and the Independence Party (2013-2016) had to dissolve parliament and call fresh elections, due to the prime minister‘s involvement in the Panama papers. In January 2017, a coalition of the Independence Party and two new parties (Reform and Bright Future) was formed – but did not last the whole year. Parliament was dissolved again and Iceland had its fourth election in eight years.

When attempts to form a four-party centre-left coalition broke down after the 2017 election, the Left Greens and the Independence Party decided to join hands in a broad coalition – despite having always been „arch enemies“ in politics. The conservatives were ready to serve in a government led by a left-socialist prime minister, Katrín Jakobsdóttir – something that had been considered impossible since the foundation of the Icelandic party system in the 1930s. The major aims of this broad coalition was to increase stability in politics, and to invest heavily in infrastructure, such as the health, education, welfare and communication systems – as the economy was in a good shape, having recovered from the 2008 crash.

The cooperation in the 2017-2021 government was smooth. The government survived the 2021 election with an increased majority – an exceptionally good result in Icelandic politics. However, support for the government in the opinion polls had gone drastically down in January 2020 – and that trend was expected to continue: government support would continue to go down and the government would lose its majority in 2021, as all other governments since the financial crisis of 2008. But suddenly everything changed – because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ideology disappeared form the political arena when all Icelanders united in fighting a common enemy, the plague. After the 2021 election, 77% of voters said that the government had been doing a good job, by far the best result for any government since 2007. Even more interesting is the fact that 89% of all voters considered that the government had been doing a good job in its fight against the pandemic. The „rally-round-the-flag“ effect was still alive and kicking in the September 2021 election – and secured a government victory.

After its electoral victory of 2021, the government parties decided to continue their cooperation under the continued leadership of Katrín Jakobsdóttir. But when Icelanders returned to „politics as usual“, ideological disagreements started to emerge, and became only worse as time passed. Inflation and interest rates greatly increased. The government became extremely unpopular according to the opinion polls. When Katrín Jakobsdóttir decided to leave politics and run for the usually non-political office of president in April 2024, the leader of the Independence Party, Bjarni Benediktsson, became prime minister. In the next few months, open disagreements steadily increased. Jakobsdóttir had by many observers been seen as the glue in the coalition. That was not the case with Benediktsson, who had previously been prime minister in the 2017 coalition that broke down within a year. In October 2024 Benediktsson declared unexpectedly that parliament would be dissolved and Icelanders would have fresh elections in November ¬ instead of September 2025 when the four-year term would come to an end. The president dissolved parliament on October 17th 2024. A campaign of only six weeks was ahead.

The glorious road to disaster for the Left Greens

Obtaining the office of prime minister in 2017 was an incredible achievement for the left-socialists. However, it was instantly clear that many left-wing activists and voters did not like their party‘s cooperation with the party furthest to the right. In the 2021 election the Left Greens lost 4.3%, while the Independence Party only lost 0.8% and the Progressive Party gained 6.6% – thus securing a government victory. The Left Greens‘ 12.6% in 2021 was nevertheless a good result compared to the disaster in 2024, when only 2.3% voted for the party.

For a decade, Katrín Jakobsdóttir had been by far the most popular politician in Iceland when she decided to run for president in April 2024. Her popularity had decreased in her last two years as prime minister – she was neverthless on the top along with Kristrún Frostadóttir, the new leader of the Social Democratic Alliance. Those two women were much more popular than all other party leaders.

When Jakobsdóttir decided to run for president, most people thought she would have an easy ride to the office ¬– only a simple majority is needed for securing a victory in presidential elections. In 1980, Vigdís Finnbogadóttir, the first democratically elected female president in the world, only obtained 33.8% of the votes in a tough competition with three male candidates.

This was however not to be. Halla Tómasdóttir was elected with 34.2% of the votes, while Jakobsdóttir received 25.2% and became second. In 2021, around 40% of all voters wanted her to continue as prime minister. No other party leader came close.

In the 2024 presidential election campaign, opinion polls showed that many left-wing voters were angry with Jakobsdóttir for her long cooperation with the Independence Party – and did not like her sudden quitting as prime minister, leaving the post to Bjarni Benediktsson. Many of those left-wing voters decided to vote tactically – simply vote for the candidate most likely to beat Jakobsdóttir. Tactical voting has usually not been important in Icelandic elections. Now it worked. However, Tómasdóttir is likely to have been elected without her tactical votes – which without doubt increased her margin against Jakobsdóttir. Many of the angry left-wingers said openly that Jakobsdóttir was obviously the most qualified candidate, but they were not willing to forgive her at this point in time. It is noteworthy, that many prominent individuals from the Independence Party supported Jakobsdóttir in the campaign, and her support among voters of that party was greater than was the case for voters of most left-wing parties.

The same anger among left-wing voters was clearly manifested in the parliamentary election in November 2024. Those angry voters first rejected Jakobsdóttir as president in June – and then got rid of all Left Greens MPs in November. The party‘s 2.3% of the votes was a record low for the left-socialist movement ever. The previous record was the 3.0% that the Communist Party obtained in its first election in 1931. In all other elections (1933-2021), the left socialists obtained more than 5% of the votes – their result was often between 15 and 20%. So it is perhaps appropriate to quote Karl Marx: history repeats itself.

Electoral volatility and fragmentation of the party system

The Icelandic National Election Study (ICENES) demonstrates that in 1983 – the first year of election studies in Iceland – around 25% of voters had switched parties from 1979. In the last four elections, party switching has been between 40 and 50% of all voters. At the moment, we do not have comparable figures for 2024.

On the other hand we know that net electoral volatility, or net gains of parties (Pedersen‘s index) was 31% in 2024, compared to 14% in 2021, 22% in 2017, 31% in 2016, 38% in 2013 and 21% in 2009. The total loss of the government parties in 2024 was the second largest in Icelandic history, 25%. The record is the government loss of the Social Democrats and the Left Greens in 2013 (28%), while the Independence Party and the Progressive Party come third – the total loss of those government parties in 1978 was 18%.

The number of parties in parliament was five after the 2009 election, six after the 2013 election, seven after the 2016 election, and eight after the 2017 and 2021 elections. In 2024, the number of parliamentary parties went down to six. The number of wasted votes was 10%, the second highest in Icelandic history – the record is from 2013, when 12% of the voters did not get any representation in parliament. Usually, this figure has been 1 to 5% since the 1930s.

The Socialist Party, the Pirates and the Left Greens obtained a total of 9% – without any representation. Electoral research shows that the voters of those parties were ideologically close to each other in 2021, both on the left-right dimension and on an authoritarian-libertarian dimension. Thus, almost one of every ten voters with largely similar views are not represented in the new parliament.

Gender equality in parliament

In recent years, Iceland has been number one in most international rankings on gender equality generally. After the 2021 election, 48% of MPs were female. Iceland then broke the European record of women representation in parliament – which had been held by Sweden with 47% since 2018. After the 2024 eletion, women constitute 46% of MPs.

The proportion of women in the parliamentary parties after the 2024 election: Social Democratic Alliance (53%), Independence Party (50%), People‘s Party (50%), Progressive Party (40%), Centre Party (38%), Reform (38%).

Coalition formation

Already on election night it seemed obvious that three of the winners would attempt to form a majority coalition, the Social Democratic Alliance, the Reform Party and the People‘s Party. The leaders of all three parties are women, Kristrún Frostadóttir, Þorgerður Katrín Gunnarsdóttir and Inga Sæland. When the first numbers of counted votes in all six constituencies had been reported, all party leaders joined a panel in the Election Night Special at the National Public Television. The three female party leaders all smiled, and seemed interested in working together.

On Tuesday, three days after the election, President Tómasdóttir appointed Kristrún Frostadóttir as formeateur of a new coalition – having had discussions with all party leaders the previous day. Formal negotiations between the three party leaders started the following day. This is the first time in Icelandic history when three women are leading such negotiations. All three leaders claimed that they expected to succeed – even though some obvious policy differences had to be settled.

Before the election, party leaders and voters seemed to be in an agreement that now it was time to form a coalition of parties close to each other on ideology and policies – parties that are far away from each other on the political spectum should not take part in the same government coalition. The three parties trying to form a coalition now seem to fulfill this criterion: The Social Democrats are moderate and left of centre, the People‘s Party is centre-left, and Reform is centre-right.

Two centre-right majority coalitions are also possible: they would include the Independence Party and the Centre Party along with either Reform or the People‘s Party. The first two parties have similar ideological positions, both are considerably further to the right than other parliamentary parties. The policy distance between those two right-wing parties and the two centrist parties (Reform and the People‘s Party) seems to be greater than their distance to the Social Democrats. However, these possibilities might be explored if the current attempt of the three female party leaders fails. History shows that the Icelandic coalition game can be quite open.