By Eva H. Önnudóttir (University of Iceland) and Ólafur Th. Hardarson (University of Iceland)

An early election to Althingi, the Icelandic parliament, took place on October 28th 2017 – only a year after another early election in the fall 2016, and the third early election since 2008. In September 2017, Bright Future, which was first elected into parliament in 2013, decided to leave their government coalition with the right-wing Independence Party, and the new centre-right Reform Party. Bright Future claimed that a serious breach of confidence had taken place within the majority coalition. This breach had to do with an issue concerning ex-convicts applications for a so-called restored honour. The issue that had been much debated during the summer months due to that a convicted child molester had been granted a restored honour and the ministry of justice was forced to make public their records about those who had been granted this since 1995. Apparently the father of Bjarni Benediktsson, the Prime minister and the leader of the Independence Party, was in those records. The father of the Prime minister had recommended in the year 2016 that an ex-convict, a child-molester, would be granted a restored honour. The breach of confidentiality between Bright Future and the Independence Party was about that the Prime minister had known about this for about two months and had not informed the leaders of his coalition parties. Bright Future left the government coalition leaving their coalition partner, the Independence Party, frustrated for not being given a chance to respond to the allegations. Instead of the political parties trying to form a new government, Prime Minister Benediktsson asked the President to call for fresh elections.

Even if the 2017 election was an early election due to an alleged breach of confidentiality, the campaign itself was in many ways a conventional campaign about issues such as health care, economic stability, welfare and taxes. All the parties agreed on the necessity of strengthening the health care system and other important infrastructure in Iceland – but advocated for different ways to accomplish those goals. Eleven parties ran for the parliamentary election and eight of them got elected into Althingi this time – a record number in modern Icelandic politics and a clear indicator about fragmentation in the Icelandic party system. The right-wing Independence Party obtained 25.2% of the vote, and lost five seats. The centre-right Reform obtained 6.7% and lost three seats and Bright Future, a centre party, only got 1.2% of the votes and lost all of its four seats. Two new parties entered Althingi for the first time: the centre-left, and some say populist, People‘s Party with 6.9%, and the new Centre Party (also placed on the centre), which was founded by Iceland’s former Prime Minister, Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, got 10.9%. Gunnlaugsson had been forced to resign as Prime Minister in 2016, due to the Panama papers scandal. Two of the opposition parties, the centre-right Progressive Party (10.7%) and the centre-left Pirate Party (9.2%) lost votes, and two of them, the centre-left Social Democratic Alliance (12.1%) and the Left-Green Movement (16.9%), which is a left party, gained.

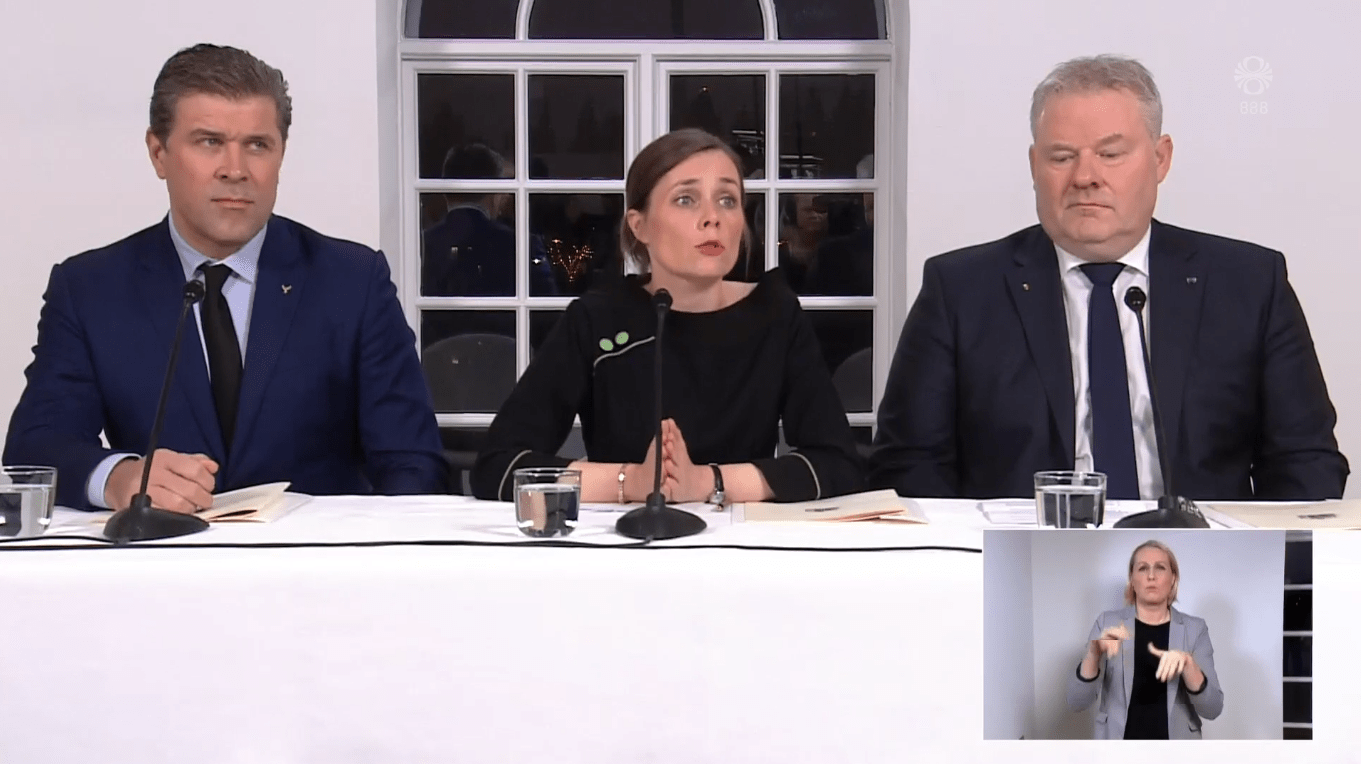

The result of the election meant that at least three parties were needed to form a majority government coalition, and that two of those would have to be the left-wing Left-Green Movement and the right-wing Independence Party, the two biggest parties that have historically considered each other as their main opponent when it comes to policy making. A few years ago it would have been considered highly unlikely, and even impossible, that those two parties would join forces in government, but that is exactly what has happened after the 2017 election, when those two parties, together with the Progressive Party, signed a government treaty on 30 November. However before the Left-Green Movement, the Progressive Party and the Independence Party started their negotiation, Katrín Jakobsdóttir, the leader of the Left-Green Movement, got a mandate from the president to form a government and at first she started a discussion with the three other former opposition parties, the Progressive Party, the Pirate Party and the Social Democratic Alliance. Those four parties had obtained together the smallest possible majority of 32 seats. After four days, the negotiation ended without an agreement. Shortly after that the leaders of the three parties that now form a government started to negotiate a government treaty.

At the time of the negotiation the Progressives seemed to favour such a coalition, as well as the leader of the Independence Party, while a large part of the grass-root of the Left-Greens seemed to strongly oppose this possibility, especially in the capital area. Nevertheless Jakobsdóttir, the leader of the Left-Greens, which is the second biggest party in the parliament, carried through with the negotiation and is now the new prime minister of Iceland. Apart from the fact that the government is formed by three parties ranging from left to right, there are at least three things that are unusual about the new government that could work in their favour. Those are their choice of prime minister, their consultation with labour market interest organisations and others while negotiating the government treaty, and the Left-Greens’ choice of a non-MP as a minister of environment.

It is unusual, but no unheard of, that the government is led by one of the smaller parties in government. Having Jakobsdóttir as the prime minister can be considered as a good and very wise strategy for several reasons. First is, that it signals that all parties in the government are willing to compromise, including the Independence Party which is the biggest party. Instead the Independence Party will get more ministries, or five out of eleven, while the two other parties will get three each. Second, Katrín Jakobsdóttir has a widespread support among voters from left to right. When leaders of the parties are rated in polls (e.g. like/dislike and trust) she has in the later years always been on top. For example in a poll since last year (the Icelandic National Election Study), where respondents were asked to rate how much they liked each leader on scale from 0 (dislike) to 10 (like), Jakobsdóttir rating was 7.1 – while the one who came second (the leader of the Bright Future) was rated 6.1. Her likeness and widespread support means that she is the best candidate of the leaders of the government parties to be able to unite and rally the support of voters from left to right, behind the government. Supporting this is a recent poll by Fréttablaðið, a national newspaper, which shows that 78% of voters in Iceland support the new government and this is a remarkable good start for a new government.

In the process of negotiating the government treaty, the three parties that now form the government, consulted both with interest organisations on the labour market as well as other types of interest organisations (e.g. for elderly and disabled), and indicated that this consultation would be continued after a government had been formed. While this type of consulting between government and interest organisations has been more common in the other Nordic countries, often referred to as consociational democracy, it has not been the norm in Icelandic politics. This development might be the government’s response to a new political reality with increasing number of parties represented in parliament and limited options to form a “pure” left or right-wing government with a minimum number of parties.

The third unusual thing about this government that could work in their favour, is the choice of Left-Greens of a non-MP as a minister of environment. By choosing a minister with a professional background in working for the environment, which is still very much in line with the policies of the Left-Greens, signals that the Left-Greens approach their work in government based more on professionalism instead of appearing as power-seeking politicians.

There are few more things that could work in the favour of this government. One is that those three parties are three established parties (not new parties) which are used to conventional politics which their cooperation will be based upon. The politicians representing those parties know each other and are familiar with how their partners work as politicians. That means that their actions and how they will respond to different situations are easier to predict compared to a new or a younger party. Second is that the government treaty is longer and more detailed than we are used to in Icelandic politics. That indicates that the parties of this coalition want to agree on as much as possible about the actions and policies of the government beforehand, in order to minimize conflict and disagreement between the parties.

Even if this government coalition stands a fair chance to survive for the whole term, there are and will be challenges. One of the key challenges will be to keep the government together. The majority of the government is now 35 MPs out of 63. Two of those 35 MPs (for the Left Green Movement) do not support the government agreement. That means de facto a majority of 33 MPs. Thus, if two more MPs defect, the government could collapse. Thus one of the main challenges of this government will be to secure a majority in the parliament by for example working more closely with the opposition than has been the usual norm in Icelandic politics.

Because this coalition includes parties from the left to the right their work will be more about managing the system instead of making systematic changes. This could work quite well as long as the economy is stable and prosperous. The government agreement states that they intend to strengthen the welfare system, education and the health care system, but there are no systematic reforms. The agreement is quite vague about what they intend to do about changing the constitution, an issue that has been debated for almost ten years (since 2008) in Iceland. The treaty only states that they will continue the work on revising the constitution in a broad cooperation among political parties and perhaps some consulting with the people. There are no promises that the constitution will be changed this electoral term.

The Icelandic economy is now doing quite well and if that continues the work of the government will be about managing the economy and make sure that the whole system works well. Given that there will not be an economic setback this government will probably be able to finish its term. Of course there could be a political scandal of the type that breaks up the government, as has happened in 2016 and 2017 – but whether a scandal will occur or not is of course not possible to predict.

Photo source: https://grapevine.is/news/2017/11/30/icelands-new-government-formed/