By José Javier Olivas Osuna (UNED)

Thanks to the high degree of political polarisation, Spain finds itself in a paradoxical situation. Although the electoral results were bad for most populist parties, they have all increased their capacity to influence governance after the last General Elections on 23 July 2023. Far right Vox lost 19 seats in the Congress of Deputies and went down from 15.1% in 2019 General Elections to 12.4% in 2023. Sumar, the left-wing coalition that absorbed Podemos lost 7 seats and went from 15.3 to 12.3%. Catalan secessionist parties Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC) and Junts per Catalunya lost 6 and 1 seats respectively, down from 3.6% to 1.9% and from 2.2% to 1.6%. The Basque separatist Bildu took a seat from the more moderate Basque Nationalist Party (PNV) and is the sole populist party that performed better than in 2019. The two mainstream parties improved their results vis-à-vis the previous General Election. The centre-right Partido Popular obtained 33,1% of the vote (20.8% in 2019) and 137 seats, while the Spanish Workers Socialist Party (PSOE) reached 32,7% of the total vote (28% in 2019) and 121 seats.

None of the two largest parties can easily form a government as they would need to secure the support of 176 MPs to get either Alberto Nuñez Feijoo or Pedro Sánchez elected as the next Spanish Prime Minister (Presidente del Gobierno). Spanish politics has a strong territorial component that makes even more difficult achieving certain pacts. For instance, Junts and PNV are conservative parties, however, their leaders have refused publicly supporting a PP’s government given that they consider this party less amenable to grant further devolution to Catalonia and the Basque Country than a left-wing government. The likely blocs that analysts considered capable of forming a government PP-Vox (170 seats) and PSOE-Sumar (152 seats) felt short of a majority.

Populists in Spain

As elsewhere in Europe, populist parties in Spain exhibit anti-establishment views, a Manichean view of society, try to exclude certain socio-economic or cultural groups, engage in historical revisionism, and appeal to popular sovereignty to promote their radical political agendas. Many of their key political messages are highly controversial and clash with the preferences of most Spaniards. For instance, Vox’ calls to eliminate Autonomous communities, repeal abortion, same-sex marriage and euthanasia laws are not shared by a sizeable part of the population. Sumar’s far-left economics paradigms and harsh critiques of the Spanish Constitutional system —which they disdainfully call “the 78 Regime”— do not resonate with the median voter either. Secessionist parties request special privileges for Catalonia and Basque country, consider their regions as “under occupation” and have pledged to achieve independence from Spain. They have displayed a disloyal behaviour regarding to the rest of Spain and its institutions and promoted campaigns to undermine the image of Spain domestically and internationally to justify an eventual secession of their regions. Additionally, all these populist parties have problematic political connections. While some Vox leaders have expressed publicly admiration for Franco, Orban and Trump; Sumar politicians endorsed Castro, Chaves and Maduro; Bildu affiliates continue to celebrate ETA terrorists as heroes, and some Catalan separatist leaders have been linked to Russian intelligence services

Russian intelligence services or paid homage to ultra-nationalists groups.

Nevertheless, mainstream parties in Spain do not apply a “cordon sanitaire” around populist parties. The PP has signed government pacts with Vox —they are coalition partners in several regions—, and the PSOE is currently ruling in coalition with Sumar and is currently trying to convince separatist parties support a new Sanchez’ government. Spaniards are not completely shocked by the willingness of the main parties to negotiate with these fringe radical parties. Many Vox leaders are former members of the PP. Spanish minority governments (González, Aznar, Zapatero, Rajoy and Sánchez) have often received support from Basque and Catalan centre-right nationalists in exchange for new “devolved” powers and other privileges for their regions. What makes the situation more anomalous now is the maximalist claims and requests by some of these parties. In particular, the demands from secessionist groups clash with the Spanish Constitution as well as with the principle of equality and redistribution. They request fiscal privileges, a general amnesty for crimes related to the illegal attempt of secession, and independence referenda (something Spanish Constitution, as most other constitutions in the world, forbids).

The two big mainstream parties don’t talk

In a less polarised context, the two large (and more centrist) parties, PP and PSOE, may have been expected to explore some sort of agreement to provide stability to a country which is still recovering from the health and economic crisis provoked from the COVID19, as well as from the secessionist political challenge. Spain was one the hardest hit countries during the pandemic and even if the peak of the Catalan political crisis was reached in October 2017 —when pro-independence parties organised an illegal referendum of independence and declared unilaterally secession from Spain—, secessionist organisations have continued to test the strength of the Spanish institutional system afterwards. Several prominent leaders, including former President of Catalonia Carles Puigdemont, remain fugitives from Spanish justice and have managed to avoid extradition so far. In 2019, after the trial and the prison sentences to other nationalist leaders, the pro-independence camp coordinated an attempt of civil insurrection termed “Democratic Tsunami”, that occupied and blocked key public infrastructures in Catalonia (such as train stations, airports, and main roads) and triggered dozens of violent riots. Moreover, Spanish Courts are currently investigating the collaboration of Russian secret services in the separatist putsch in Catalonia.

However, in Spain the scenario of a Grand Coalition has been quickly ruled out by many pundits. Ideological and affective polarisation have been growing over the last few years. Thanks to a sort of contagion effect, the antagonistic and moral discursive tone used primarily by populist parties has spread also to non-populist parties on the right and on the left of the political spectrum. A great deal of Spanish political debate is currently reduced to hyperbolic claims aiming to delegitimise and demonise the political adversary. Political leaders not only accuse each other of lying and of corruption, but also use frequently expressions such as “terrorists,” “Bolsheviks,” “fascists,” and “Francoists” in the Spanish Parliament and media to attack their rivals. This increasingly hoarse communication style seems to be contributing to the reification of an insurmountable rift between the political blocs in Spain. And this discursively constructed rift is limiting the perceived acceptability of any possible negotiation or pacts between the left and right blocs. The unusually aggressive rhetoric used by the PP and PSOE towards each other over the last few years —and specially during the recent electoral campaign— is also hindering any kind rapprochement between the two big parties that have ruled Spain over the last four decades. Partisan animosity is not linked to personal socio-economic conditions or specific policy issues such as immigration, but largely the result of perceived polarisation among elites, ideological extremism and territorial identities.

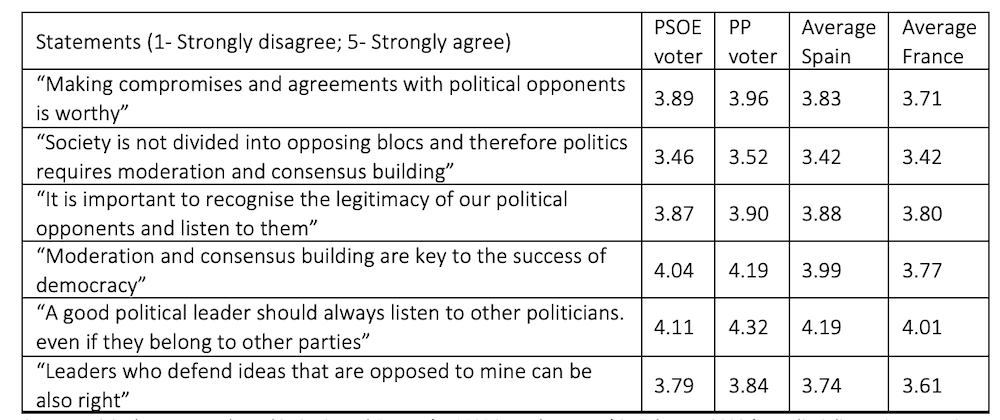

Spain is not alien to consensus building. On the contrary, the Spanish transition was an example of inter-party agreements that paved the way to a solid constitutional system as well as to in-depth economic reforms that brought prosperity and social justice to a country that had endure a long dictatorship. A recent longitudinal analysis of parliamentary activity in Spain between 1980 and 2021, demonstrates that laws at the regional and national level were often approved via large multi-party agreements. Moreover, the largest parties signed pacts to develop the decentralised Autonomous Communities governance system (1981), to fight ETA terrorism (1987, 1988 and 2000), to reform public pensions (1995), to depoliticise justice (2001), and to fight gender violence (2017). When asked to rate the level of agreement from 1 to 5 with statements that refer to consensus building, Spaniards show largely in favour (and more so than French people).

Source: original survey conducted in Spain and France (n=1500 in each country) in February 2023 (Interdisciplinary Comparative Project on Populism and Secessionism. Department of Political Science and Administration. UNED)

Why are state pacts among the main political parties so difficult to reach now in Spain?

Spanish political culture or institutional system do not preclude such negotiations or agreements. Rather than a structure-based explanation we should investigate agency and ideas-based factors to understand this apparent deadlock.

Firstly, political strategists within the two big parties believe that fuelling negative emotions towards their main adversaries is a stronger mobilisation tool than developing public policy proposals. The success of populist parties like Podemos and Vox that thrived appealing to prejudices and fears has contributed to this interpretation. Repeated aggressive communication campaigns by the PP and the PSOE trying to discredit the rival party from a moral stance and presenting it as undemocratic have ended up affecting the perceptions of party members and voters. They are somehow prisoners of their own short-term communication tactic. Discursive U-turns are not rare in Spain. But in the context of high polarisation, backtracking and approaching the other centrist party would expose them to attacks from far-right and far-left parties and to potentially lose their more radicalised voters who may feel betrayed or find incongruent a more conciliatory approach.

Secondly, populist parties are also interested in widening this rift between blocs. They are aware that with their current low levels of support (and downward trend), their best (or only) chance to exert power is via coalitions or government pacts with one of the two major parties. Their finances also depend on being in the government and some of these populist parties like Podemos or Junts are currently facing economic difficulties (parties rely on donations from party members in government jobs). A grand coalition or state pact in Spain between the PP and the PSOE would make them largely irrelevant in policy terms in the next four years and limit their chances of getting political appointees in the administration and public bodies. That coalition would also impede their goal of turning Spain either into a very conservative unitary State, as Vox desires, or into a confederation of smaller countries as suggested by Sumar and the secessionists groups. Hence, populist parties are exerting great pressure via media and social networks to rule out this possibility. They have de facto created a sort of “cordon sanitaire” around the PP.

Thirdly, since the PP is the party that obtained a higher share of votes and seats in the elections, they would likely request to be senior partners in a grand coalition. Several historical PSOE leaders dislike the idea of a new government that would depend on separatists —who they fear would “blackmail” the Government each time a law or budget would need to pass—. However, Pedro Sánchez and his entourage have very quickly and firmly silenced those critical with the negotiations with Sumar, ERC, Junts and Bildu and have launched a communication campaign that seeks to frame the situation as a binary choice between a “progressive” PSOE-Sumar government supported on nationalist and secessionist parties or an “extreme-right” government of PP-Vox. This is a false dichotomy as there are two other possibilities which are: a) PSOE could accept the invitation to negotiate that Nuñez Feijoo made to Sánchez (the latter challenged the former to six political debates during the campaign but refuses to meet and negotiate now) and b) Sánchez could call new snap elections that, if the trend observed continues, would further weaken populist parties, and facilitate a government that would request fewer populist partners.

This communication campaign has been quite successful at imposing this Manichean frame. The PSOE and Sumar have been supported by many left-leaning media and political influencers who have whitewashed the image and controversial claims of the separatist parties which support is required for this “progressive” coalition. This was not an easy task, as secessionist parties want to limit redistribution in Spain, exhibit a rather nativist understanding of society, and constantly refer to historical, linguistic, and territorial rights that are at odds with mainstream interpretations of left-wing ideology in democracy. Large amounts of cherry picking, analytical double standards and cynicism have been employed to turn into a dominant collective interpretation the impossibility of a PP-PSOE pact and the desirability of an unstable government grounded on those who openly challenge the Spanish constitutional order.

It is difficult to predict what will happen in the coming weeks in Spain. In other democracies the results of the General Election and the radical stance of the populist parties involved would be read as leading to new snap elections or to some sort of government pact between the two big parties. However, due to polarisation and the well-nurtured rift between the PP and PSOE, few Spaniards are hopeful of a grand coalition and the much-needed structural reforms that such Government could launch (e.g., education, justice, public administration, etc.). Instead, they witness how the governability of Spain is being decided by Puigdemont, a radical-right secessionist fugitive leader that lives in Belgium.

Populists in Spain may have lost much of their popular support, yet affective and political polarisation fuelled by political strategists and pundits, can turn them into the real victors of the 23 July elections.

Photo source: https://www.itv.com/watch/news/spain-faces-political-gridlock-after-election-fails-to-produce-clear-winner/6fpvkgg