By Jonathan Arlow (University of Liverpool)

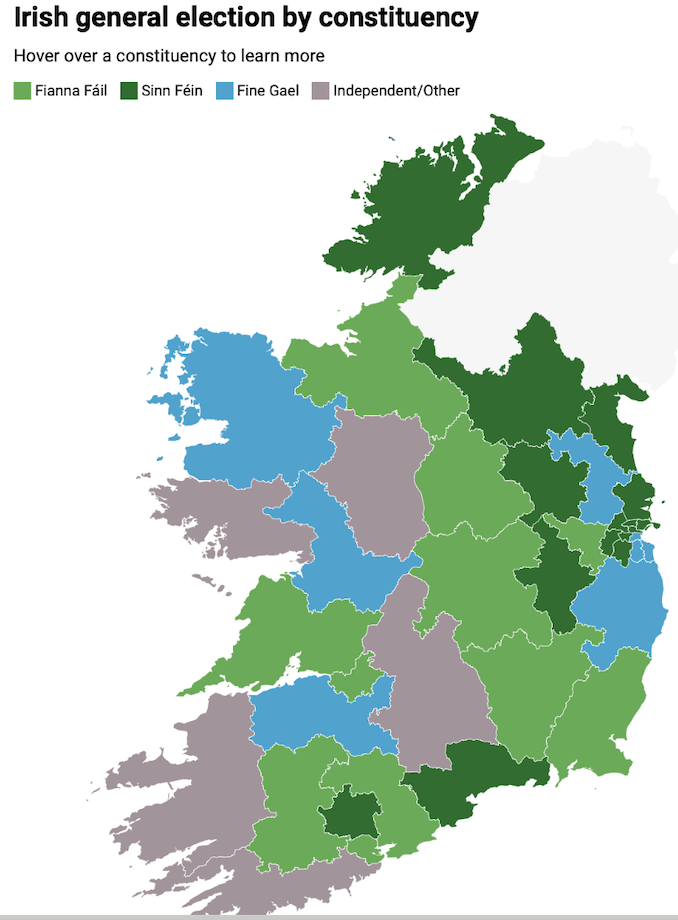

The General Election continued the trend for fragmentation in the Irish party system, with the three big beasts of Irish politics – Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael, and Sinn Féin – all winning between 19 to 22 per cent of the vote share. The Irish electorate has also bucked the trend for the removal of incumbent governments in the Global North, instead returning a government led by Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael. Fianna Fáil won 48 seats on 21.9 per cent. This is ten seats more than its traditional rivals in Fine Gael on 20.8 per cent, but if that party returns to government, it will be its fourth consecutive term in office since 2011. Unlike many other European states, the Irish government enjoys low unemployment and a large budget surplus, fuelled by booming corporate tax revenue. The outgoing government has delivered several giveaway budgets – the last in October 2024 – that cut taxes and increased spending to shelter people from the cost-of-living crisis. Importantly, this increased public spending continued the Irish tradition of social provision relying on cash transfers to citizens rather than serious reform or expansion of the welfare state.

In 2016, it took Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael 63 days to agree a ‘confidence and supply’ agreement for a minority Fine Gael led government. In 2020, it took them 140 days to agree a coalition government with the Green Party, which involved a rotating Taoiseach (Prime Minister) between Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael. This may be the only sticking point between the two parties when negotiating a second programme for government. Fine Gael wants the same ‘parity of esteem’ agreed in 2020 and for its leader – Simon Harris – to serve as Taoiseach for the second half of the government. This is problematic for Fianna Fáil due to its increased Dáil representation, which suggests it should lead the government. However, the leaderships of both parties have vehemently ruled out Sinn Féin as a coalition partner due to its militant past and ‘anti-enterprise’ policies. This means that there are no other options to form a government and Micheál Martin – Fianna Fáil leader – is unlikely to push Fine Gael onto the opposition benches by being overly intransigent on this issue.

In the 1980s, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael were described as ‘programmatically indistinguishable’. This policy convergence has increased since then and they have been labelled the ‘identical twins’ of Irish politics. There are differences in terms of history and political culture, but on policy there is relative unanimity. In effect, they are two centre-right parties catering to the same interests that advocate moderate change to the status-quo. This general election saw these two old opponents transfer votes heavily between each other under the Proportional Representation Single Transferable Vote system, with nearly one third of their voters choosing the other party as their second preference. This means that, in many constituencies, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael are effectively helping to elect each other’s candidates, a level of electoral symbiosis between the parties that would have been unthinkable before the Great Recession. Exit polling showed that a coalition led by Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael was favoured by 49 per cent of the electorate, and that their voters tended to be homeowners who felt their standard of living had improved or stayed the same over the past 12 months. In contrast, those who voted for Sinn Féin tended to not own their own homes, felt their standard of living had decreased, and were more likely to be under 35 years old.

The Election Campaign

The three-week election campaign began with Fine Gael leading in the polls, at 25 per cent, but they dropped six points during a tough election for the party. Nearly half their incumbent TDs had retired before the election, and this loss of experience may have impacted the party’s performance, as there was a series of self-inflicted errors both before and during the campaign. The giveaway budget in October, combined with manifesto promises for future tax cuts and spending increases, undermined their case to be prudent managers of the economy. Michael O’Leary (CEO of Ryanair) mocked teachers at a party event, which was not well received by voters. One of their electoral candidates – Senator John McGahon – was previously involved in a violent incident which undermined their claim to be the party of law and order. In one leaders’ debate, Simon Harris denied responsibility for the cost overruns of the National Children’s Hospital (which will be the most expensive hospital in the world when it is built) even though he was Minister of Health when the contract was agreed. Then, in what became the stand-out incident of the campaign, he failed to show compassion to a distraught care worker while canvassing in Kanturk (County Cork), which was recorded by one observer and received millions of views on social media.

Before the election Harris was known in the media as the ‘Tik Tok Taoiseach’ due to his good communication skills. But the election revealed his communication style as superficial – even facile – and the party’s mistakes played to Fine Gael’s reputation for being arrogant, elitist, and out of touch. Fianna Fáil was the biggest beneficiary of this collapse in Fine Gael support during the election. Micheál Martin performed well in leaders’ debates and on the campaign trail, offering himself to the electorate as a ‘safe pair of hands’, which contrasted with the inexperience of Harris and the unknown quantity of Sinn Féin.

Only 18 months before the election Sinn Féin had a credible – if uncertain – path to leading the next Irish government. A series of scandals involving party officials in the lead up to the election did not help Sinn Féin. But it was the rise of immigration as a salient issue for voters that shattered the coalition that Sinn Féin built during the 2020 election, consisting of the working class and disaffected middle-class youth. This led to a dramatic decline in Sinn Féin’s support, from a high of 36 per cent in July 2022 to 19 per cent by polling day. Recent surveys have shown that former Sinn Féin supporters view immigration as their number one concern, and the voters who still support the party view the housing crisis as the most important issue.

However, Sinn Féin will be relatively pleased to have improved significantly on their 11.8 per cent vote share in June’s local elections. Fortunately for the party, immigration was only fifth place on people’s most important issues in this election, behind housing, the cost of living, and health, all issues which play to Sinn Féin’s left-populist strengths. Sinn Féin produced the most credible and detailed policy documents of any party on health and housing. Their manifesto – at 180 pages – was the longest they ever produced, North or South. Also, a potential electoral breakthrough by far-right political actors never materialised, which maintained Sinn Féin’s dominance in urban working-class areas. Sinn Féin’s leader, Mary Lou McDonald, displayed an easy rapport with voters on the campaign trail. She did well during interviews and leaders’ debates, but at times she could be less impressive on policy detail. Significantly, improved vote management in areas where Sinn Féin are strong – such as Dublin South Central, Cavan-Monaghan, and Donegal – helped them return two TDs in a single constituency.

But despite a good campaign that saw them stabilise on 19 per cent vote share and come second in terms of Dáil seats, Sinn Féin failed to convince sufficient Irish voters that they offered a credible and safe alternative for change to the status-quo. They were also disproportionately hurt by the low turnout of 59.71 per cent, which was lower again in some predominantly working-class constituencies. On a positive note, Sinn Féin will remain the largest party of opposition, and the experience of their sitting TDs has improved significantly during the last Dáil. They are in a strong position to take advantage of an anti-incumbency shift in the electorate should that occur in the next five years. For example, Ireland’s economic position is strong but precarious due to Trump’s tariff plans and the economy’s reliance on US corporations. It is also possible that Sinn Féin in the South could become an Irish version of the post-war Italian communists: a competitive anti-systemic opposition party that never quite makes it into government.

Smaller parties

The Labour Party and the Social Democrats both won 11 seats in the Dáil. A significant achievement for two small parties, that has resulted in talk of one or both becoming potential coalition partners. The radical left – People Before Profit / Solidarity – will be disappointed to lose two seats despite a slight increase in their vote share. Interestingly, with three seats in a national parliament this group remains the most electoral successful Trotskyist movement in the Global North. Aontú – a party that emerged from a split in Sinn Féin – gained an extra seat in the Dáil and improved its vote share to 3.9 per cent, which entitles it to state funding. It resembles the Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW) party as it combines social conservatism on issues like abortion and immigration with left-wing positions on the economy. Also, Independent Ireland, which is a loose party alliance of conservative independent politicians, gained 3.6 per cent vote share and four seats. The Green Party had a devastating election following coalition with Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, losing all but one of their seats. There is a long pattern of smaller parties being punished by their voters after the compromises of coalition with Fianna Fáil or Fine Gael. In government, the Green Party was squeezed on both sides of the environmental crisis. It was seen as not delivering enough on policy for some, but doing too much for others who oppose carbon taxes and increased environmental regulation.

Coalition negotiations

Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael only need two extra seats to give them a majority of 88 in Dáil Éireann, but around 95 seats are needed to give them a comfortable working majority. Labour and the Social Democratics seem wary of entering coalition given the electoral risks and the treatment of the Green Party in government, who had their preferred policies undermined and were briefed against by the two bigger parties in the lead up to the general election. Importantly, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael may not be willing to make significant concessions on policy and could form a government with the support of independent TDs instead. Independents have usually traded their Dáil votes in return for benefits to their constituency rather than Cabinet positions. There are currently eight independent rural TDs in the ‘Regional Group’ within the new Dáil, all of whom have a stated desire of entering programme of government negotiations. This regional group may make a more desirable partner for government than Independent Ireland, who have definitively stated that they would require Cabinet positions in return for their support.

This election saw an increase in the gender quota, with every party required to run at least 40 per cent women candidates. This resulted in 44 women TDs elected or 25.3 per cent of the Dáil, an increase of just 2.8 per cent from the 2020 election when the quota was 30 per cent. The parties seem to be following the letter of this law but not the spirit, by running new women candidates in support of more well-known male candidates. Also, incumbency matters in elections and most of the Dáil is male. Bringing similar gender quotas into local elections may increase the number of women candidates filtering through into the national parliament.

A second coalition government marks a significant achievement for Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, especially considering the ongoing crises in housing and health. But it should be understood in the context of their combined vote share reducing from 68.9 per cent in 2007 – before the sub-prime crisis – to 42.7 per cent in 2024. The fact that these parties, which have dominated politics since the state’s foundation, must now govern together marks a significant electoral shift, despite the superficial stability of a second coalition government. It suggests that the one constant in the coming years will be continued voter volatility.

Photo source: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/ireland-election-results-sinn-fein-fianna-fail-b2657949.html