By Ryo Nakai (The University of Kitakyushu)

Latvia had a general election on 6 October 2018. The results awarded seats in the Saeima, the parliament of the Republic of Latvia, to seven parties including three newcomers. Some notable aspects of the election include the following: the current government parties were defeated, a party friendly to Russian speaking minority obtained the first place, and a 5-Star Movement-like party took second place. Results recorded the second largest effective number of political parties, and the lowest voter turnout. The battle over coalition formation will start immediately.

Pre-election landscapes

Latvian electoral politics are among the most unstable, volatile and fragmented in Europe. In recent elections, however, four major parties survived. The top-runner, Harmony or Concord (Saskaņa), is supported by Latvia’s Russian speaking populations, which constitute the most important ethnic minority in the country. While Harmony came first in the two previous elections (2011 and 2014), it was excluded from coalitions and never joined the national government. This was mainly due to its strong commitment to Russian speakers, its inconsistent stance on Latvia’s national integration policies and historical perceptions, and its partnership with Putin’s United Russia party

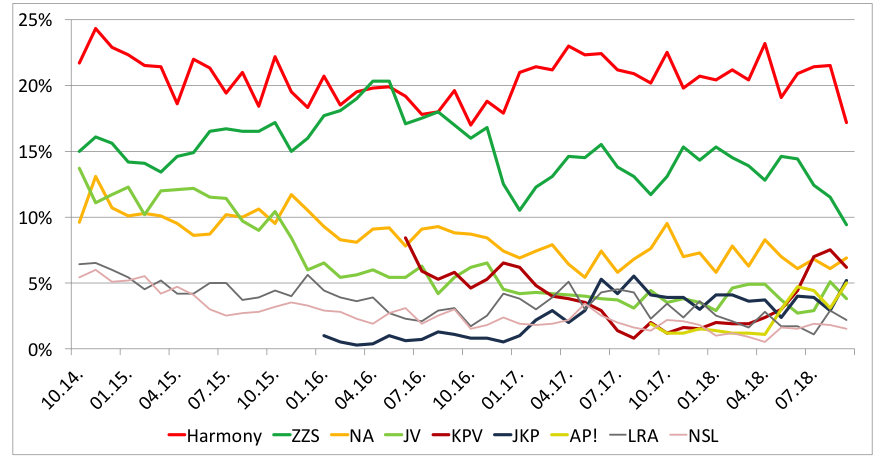

Some newcomers appeared to be promising candidates during the campaign season. The party ‘Who Owns the State?’ (KPV LV: Kam Pieder Valsts) was created by the famous ex-actor & radio host, and unaffiliated MP, Artuss Kaimiņš, in May 2016. Although its popularity declined after its formation, it rapidly regained popularity just a few months before the election (see Figure 1). In part, this reflects Kaimiņš’s populist strategies (explained below) and dramatic detention of him inside Saeima building in front of TV cameras in June 2018, both of which gave voters the impression that Kaimiņš and the KPV were outside existing political groups.

The New Conservative Party (JKP: Jaunā Konservatīvā Partija) was formed in 2014 as the small personal party of a former Minister of Justice – Jānis Bordāns. The JKP rapidly transformed its membership by accepting many former staff members of the Corruption Prevention and Combating Bureau as new members. JKP became popular rapidly after it welcomed a very well-known former KNAB member, Juta Strīķe. As a result, the JKP succeeded in winning seats in the 2017 municipal elections. Another party, For Development/For! (A/P!: Attīstībai/Par!), which included a few famous ex-ministers or high officials as party members, was also expected to win seats. They were formed in 2018 by several liberal parties and movements, mainly with social liberal orientations (e.g. they claim introduction of civil partnership and LGBT equality, while Latvia constitution prohibit same-sex marriage). Its prime minister candidate Artis Pabriks was a Unity member in the past, and served as Minister of Defence and as member of the European Parliament.

In the previous 2014 election, two new parties succeeded in winning seats: Latvia’s Regional Alliance [LRA] and For Latvia from the Hearts [NSL]), owing to their party leaders popularities. Both opposition parties are now less popular; the electorate views them as having done nothing. Although Kaimiņš was once a member of the LRA, he rejected the party. Most NSL MPs, apart from the party. These ‘earlier’ new parties were therefore teetering on the brink between survival and collapse.

Figure 1. Polls of the major parties from previous elections (October 2014-September 2018)

Data source: The research centre SKDS, and by courtesy of its director Arnis Kaktiņš.

Results and Implications

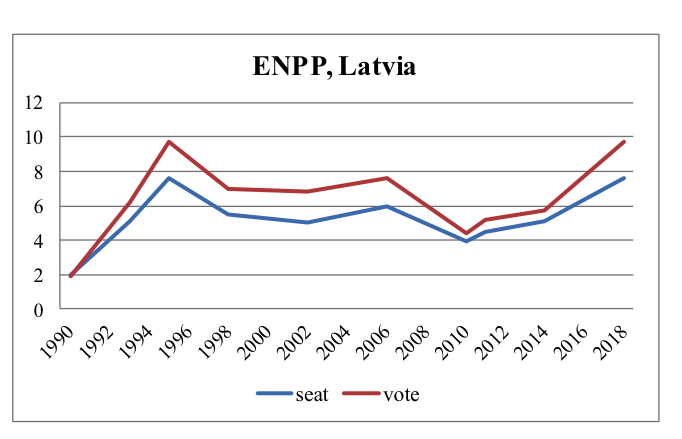

The electoral results of last Saturday Saeima elections (100 seats) were as follows: Harmony: 23 seats with 19.9% vote, KPV: 16 seats with 14.1% vote, JKP: 16 seats with 13.6 % vote, A/P!: 13 seats with 12.0% votes, NA: 13 seats with 11.0% votes, ZZS 11 seats with 10.0% votes, JV: 8 seats with 6.7% votes. LRA and other parties failed to pass the 5% threshold to gain a seat in Saeima. Seats are allocated through proportional representative system with St. Lague method in five constituencies. Harmony gained first place in Rīga and Latgale (east Latvia) constituencies, while KPV attained first place in Kurzeme and Zemgale constituencies (west and south Latvia). Voter turnout (54.6%) was lower than in the previous elections (58.9%). The Effective Number of Political Parties is 6.4 by seat and 8.2 by vote. This is the second highest number after 7.6 (seat)/ 9.7 (vote) recorded in 1995 general elections (figure 2). We can say that Latvian party politics backslide to 1990s age in terms of fragmentation, party instability and electoral volatility.

Figure 2. Effective Number of Political Parties by seat and vote, Latvia national elections

The one of the most successful parties in this election was the KPV. The KPV party leader, Artuss Kaimiņš, is a political outsider. His self-promotional style is pure populism, attacking existing parties and the media as corrupt elites. His main policy manifesto focuses on reforming the political administration. A political scientist D. Auers has portrayed that the European party most similar to the KPV is Italy’s 5-Star Movement. Its catch-phrase, ‘the state must start with itself (Valstij jāsāk ar Sevi),’ is little bit confusing; it refers to politically alienated voters, especially young voters, who feel that existing political elites do not care about them. It aims to reform the state administration or government from its own base. Although it is not uncommon in Latvian that new parties win 1st or 2nd place in the election, they have usually shown, more or less, cooperative attitude with existing parties. In that point, the KPV’s militant stance to all existing political parties is very interesting. A full-spec bona fide populist party has emerged in Latvia’s electoral politics. It is worthy to mention that KPV is very popular among oversea voters, and about 35% of votes that KPV take in capital Rīga constituency came from oversea voters.

The JKP closed up the KVP, taking 13.6% of votes. This is another victory for them, after securing 13.7% of votes in capital city Rīga municipal election in 2017 June. Most of prominent MP candidates came from members of Rīga municipal council. This means that the local election functioned as a springboard for JKP’s success in national politics. Although JKP is also new face for national politics, its core members has long career and experiences in the field of politics and public administrations. Then the impact of the winning by JKP is different of KPV the political outsiders.

One again, Harmony has won, gaining first place, as happened in the 2011 and 2014 elections. The fact that a pro-Russian party has won first place in the Latvian election will gain the attention of the international media, but that fact is not surprising in the context of Latvia’s recent electoral politics. As U. Bergmane has argued, the question ‘is not which party will obtain most of the votes. Everybody knows that most likely it will be the Russian-speakers’ party Harmony. The real question is whether Harmony might finally find coalition partners to craft a majority’. Although Harmony won first place, its support rate (19.9%) is lower than with previous elections (23.0% in 2014, and 28.4% in 2011). Harmony’s recent political strategies have focused on attracting more ethnic Latvian voters, in addition to their consolidated ethnic Russian voters. To achieve this the party has tried to present itself as a typical European ‘Social democratic’ party rather than an ethnic minority party, ending its ‘official’ cooperation with United Russia. The face of the party, Nils Ušakovs – the mayor of capital city Rīga – has led an electoral campaign to demonstrate that the party has sufficient experience to govern the capital city. The present electoral results, however, show that these efforts have not been particularly successful in increasing supports for Harmony. The party’s strategy could therefore be reconsidered over the next few years.

JV’s loss suggests that liberal forces in Latvian party politics are in danger. A/P! got fourth place as an alternative liberal party though. The number of seats (21) won by JV and A/P! is the lowest number over the last two decades, as far as centre-liberal factions go. Since 2000s, liberal JV and its predecessors functioned both as ‘glue’, connecting political parties in the ideologically polarized Latvian party system, and also as ‘filler’, creating coalitions with a stable majority of seats. In fact, the previous Dombrovskis and current Kucinskis governments, which have incorporated the JV party, have demonstrated relative longevity (4 years, 10 months and 3 years, 8 months, respectively), in comparison to the past Latvian coalition government, which survived for less than two years. The loss of a strong liberal party, in combination with higher number of effective political parties, creates a situation in which future Latvian party politics are once more at risk of instability.

Who voted for the newcomers? A quick look at the data

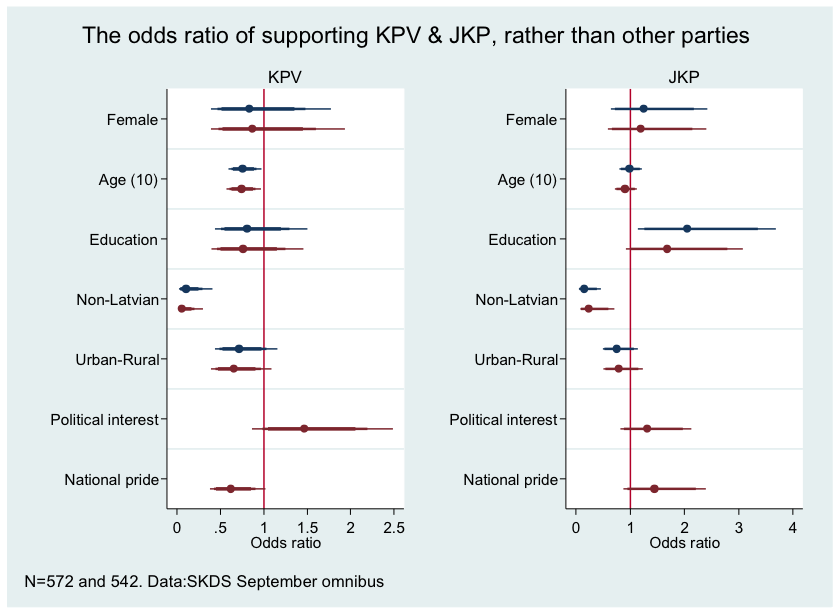

The following section provides a preliminary analysis of supporters for new parties. Author carried out a survey in September in cooperation with SKDS – the leading pollster in Latvia. A simple logistic regression was used to determine whether respondents supported KPV or other parties, or JKP or other parties; those who answered, ‘I don’t know’ or ‘I do not participate in elections’ were excluded. The results reveal the following tendencies (see Figure 3).

As a demographic, the young, urban Latvian electorate tends to support KPV rather than other parties. More interestingly, respondents with a higher level of political interest and a lower level of pride at residing in Latvia tend to support the KPV. This implies that politically active voters who are dissatisfied with Latvian society tend to support the KPV, rather than other political parties. The fact that dissatisfied but politically active voters are attracted to the KPV suggests that the party’s populist strategies (designed to attract dissatisfied voters) are succeeding, as intended.

JKP supporters didn’t show a clear trend. Higly educated Latvian voters tend to support JKP than other parties, but other variables do not have clear effects. We also checked effects of respondents’ policy preferences (not included in Figure 3), and found that there are no clear policy preferences among JKP supporters, compared to other parties supporters. It is seems that JKP succeeded to attract support from a broad range of electorates.

Figure 3: The odds ratio of supporting KPV & JKP, rather than other parties

Note: The bars indicate a confidence interval of p <.10 and p <.05.

What comes next? The battle of coalition formation

If Harmony, a pro-Russian speaking minority party, succeeds in forming a coalition and taking part in national governance, it will be the first time this has happened in Latvia since the restoration of independence. Such a change could lead to drastic alterations in the national integration policies and diplomacy with the Russian Federation. Most Latvian political parties, however, have signed a pre-election agreement not to form a coalition with Harmony. The exception was the KPV. During this electoral campaign season, the KPV party had not clearly rejected the future possibility of cooperating with Harmony; therefore some international media have paid attention for possible coalition between Harmony and KPV. However, Kaiminš dramatically expressed that his party KPV will not cooperate with Harmony in a candidate debate TV programme just three days before the voting day. Result also shows that Harmony-KPV coalition cannot reach majority. Therefore, this coalition has a very tiny chance of being formed.

Although the current coalition members, ZZS, JV, and NA, have failed to obtain a majority (32 seats in total), they could do so by simply adding the JKP and A/P!. This four or five parties’ right-to-centre coalition could therefore become feasible. The only one minimum winning coalition among five parties is JKP-A/P!-NA-ZZS coalition with 53 seats. This coalition, however, contains a risk of conflicts between JKP and NA as rivalry, and between JKP corruption fighter and ZZS’s pork barrel politics. Including JV would create more stable 61 seats majority. KPV will also try to exercise its political leverage by intervening negotiation process. Although coalitions with five and more parties have not been rare in the past Latvian party politics, those needed long time period to make compromise between parties, and usually collapsed soon. The same will occur in the upcoming coalition negotiation and formation. Bordāns and Aldis Gobzems, as prime minister candidates from JKP and KPV, respectively, will play leading roles in this negotiation processes. A policy analyst I. Kažoka noted that new government formation would likely not be in place until next year. At any rate, any possible this centre-right coalition will include new parties, and then if such new coalition is formed, many policy changes may also occur.

A minority government is also another possibility. For example, three or four parties from centre to right form a cabinet with parliamentary support from all parties but Harmony. Such a minority cabinet would, of course, face severe challenges when trying to run a credible government. Even a snap election will be likely.

Summing-up

During the electoral campaign season, it was expected Kaimiņš will be in centre stage of political soap opera after the election. Electoral results turned out that, however, this opera apparently has a greater number of prominent actors and more complex story. If politicians want to form a stable majority coalition, any possible coalition will need to accommodate larger policy changes in future, by including several newcomers. On the other hand, if MPs agree to form a minority government, they will make future Latvian politics more unstable. Either way, the next four years of Latvian politics will be more unpredictable than usual!

Photo source: http://www.delfi.lv/news/saeimas-velesanas/zinas/partijas-saks-apspriesanos-par-sadarbibu-pec-saeimas-velesanam.d?id=50467917