By Grant Mitchell (Keele University)

Introduction

After weeks of declaring that there would be no general election until 2020, Theresa May surprised the nation by calling for a general election before 2020. Unlike in previous elections, the introduction of the Fixed-term Parliaments Act (2011) removed from the Prime Minister the power to call snap elections and therefore Theresa May needed the approval of parliament which she got a day later.

Theresa May justified her call for a snap election on the basis of the Brexit negotiations that were soon to come. However, for all the emphasis placed on Brexit at the outset, it would not come to dominate the campaign as many might have suspected, although it certainly flared up from time to time.

The context: electoral system, alliances and other arrangements

The United Kingdom operates a single-member plurality voting system known as First Past The Post (FPTP). Under FPTP, voters place a single cross on a ballot paper next to their preferred candidate and the candidate with the most votes in a given constituency wins. All other votes are discarded. This certainly favours pre-electoral alliances.

Within a few days of the election announcement the Green and Scottish National parties sought to collaborate with both Labour and the Liberal Democrats in order to prevent another Conservative victory. Tim Farron, leader of the Liberal Democrats, reaffirmed his party’s opposition to an electoral pact with Labour, citing differences over Brexit and the perception that Corbyn is an electoral liability. The Liberal Democrats further ruled out a coalition with both the Conservatives and Scottish Nationalists. Similarly, Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the Labour Party, ruled out any coalition agreement with the Scottish Nationals, Greens, and Liberal Democrats.

Notwithstanding national agreements, local arrangements were made across the country. The Greens withdrew themselves from 22 contests across England and Wales, while the Liberal Democrats agreed not to contest the Green-held seat of Brighton Pavilion. The United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) indicated that they would not nominate candidates for contests where a strongly pro-Brexit Conservative candidate could win. It should be noted, however, that the snap election seemed to catch the already badly organised UKIP off guard who failed to nominate a full slate of candidates.

The Campaign and the polls

Part One: Strong and Stable

Just after Theresa May announced the election, there was talk of a three-figure majority for the Conservatives. Polls were showing the party on an impressive ~48percent to Labour’s ~25percent. This was an historic lead fuelled, in part, by the collapse of UKIP. The Conservative offensive primarily focused on the ‘strong and stable’ leadership qualities of Theresa May and the inevitable ‘coalition of chaos’ that would occur under Jeremy Corbyn. However, while the Conservatives maintained a strong lead, Labour began gaining some ground, rising to ~3percent ahead of their official manifesto launch.

Part Two: Weak and Wobbly

The launch of the Labour Party manifesto marked the beginning of a shift in public opinion. Labour began to catch-up with the Conservative Party and the gap between them began evaporating. Jeremy Corbyn and Labour were basking in the media spotlight with a manifesto whose central commitments proved relatively popular. The Conservative manifesto, by contrast, was a blunder. The manifesto contained a number of policies that would prove be very unpopular among a core electorate of the Conservative Party: older voters. They proposed to scrap winter fuel payments for wealthier pensioners and to abolish the so-called triple lock on pensions, instituting a new double lock instead.

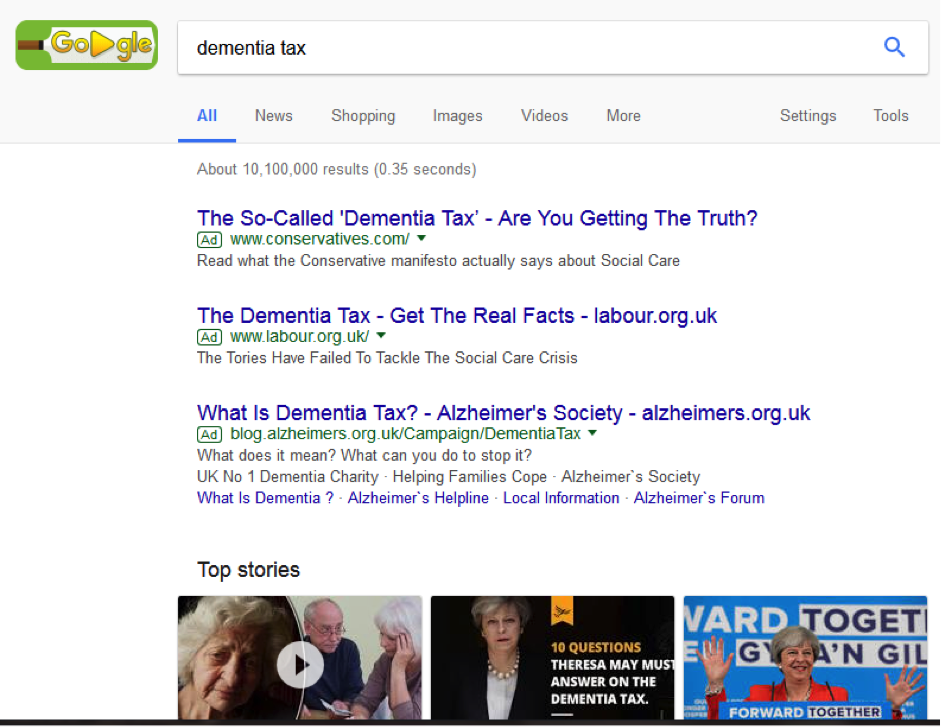

Most criticised, however, were the Conservative proposals over social care that would see older people paying potentially much more for their social care. [2]

Labour vigorously attacked the Conservative Party for instituting a “dementia tax”, to which the Conservatives responded by buying up advertising on Google for anyone who searched ‘dementia tax’.

A couple of days after the initial announcement, and after the party declared no changes were to be made to the policy, changes were made to the policy. Theresa May stated that there would be an ‘absolute limit’ on the amount someone must pay for their social care, a move widely interpreted as a u-turn. The effect of this was to burst Theresa May’s ‘strong and stable’ bubble and it resulted in a deflation in the Conservatives’ poll lead. The Conservatives were now at roughly ~43percent while Labour had clawed their way to around ~35percent: higher than at any point since the last general election. Over this period, Theresa May had been accused by journalists and opposition politicians of being less ‘strong and stable’ than ‘weak and wobbly’.

Stage three: Events dear boy, events!

On the 22nd May an Islamic terrorist attacked the Manchester Arena following a convert by American singer Ariana Grande. Twenty-three adults and children, including the assailant, died, while 116 were injured, some critically. In response, political parties terminated their campaigning. Polling companies also terminated their activities.

Politicking started up again later that week and polling evidence suggested that the tide against the Conservatives had slowed down, with a marginal increase in the gap between them and Labour.

On the 3rd of June, the UK experienced yet another terror attack, this time in London, and as before, the mainstream political parties suspended their national campaigns. Following the resumption of campaigning, Labour sought to attack the Conservatives, and in particular Theresa May who was Home Secretary under the previous government, for their role in scaling back the size of the police by some 20,000 officers between 2010 and 2016. The Tories sought to reinforce their lead on defence and security matters by drawing public attention to not only Jeremy Corbyn’s previous statements on the issues of defence, security, and specifically shoot-to-kill, but also of Diane Abbott, the Shadow Home Secretary.[3]

The last few days seemed to be dominated by a focus on security issues, which is hardly surprising given events in London and Manchester.

The campaign in the regions

In Scotland, the primary dynamics of two-party competition took place between the Scottish Nationalists and Conservatives on the never-dying issue of Scottish Independence. The Conservatives north of the border, under the leadership of Ruth Davidson, have focused much of their attention on being the party of the Union, hence their widespread use of the traditional (and formal) party name: Conservative and Unionist Party.

While the Conservatives argued that the SNP spent far too much time obsessing over the constitutional question, it was the Conservatives who have made the constitution central to the campaign believing it to be their best chances of making solid gains in Scotland.

The SNP, by contrast, focused more on social policies, where it believes it is more in tune with Scottish public opinion. In this battle, both Labour and the Liberal Democrats had been effectively squeezed out. As the constitutional question had come to dominate Scottish politics, there was no room outside of the big two who were fervently opposed and in favour, respectively, of British Union.

Wales was dominated by the same two-party competition as had occurred within England; which caused some confusion among voters given the unclear nature of the pledges in relation to the devolution settlement in Wales. Early on in the campaign, and following a weak period for Labour, the polls showed a strong reversal of fortunes with the Labour Party reclaiming their strong position in their traditional heartlands. However, while the Conservatives fell back somewhat, they still maintained a strong position (+8% on their 2015 election performance).

The issue of Brexit upon the agricultural industry within Wales attracted particular attention. The majority of farmers voted in favour of Brexit, however, were concerned to ensure free trade continued.

It should be noted, of course, that the dynamics of party competition differed in Scotland and Wales as both are governed by devolved assemblies whose governments are controlled by the SNP and Labour respectively, and therefore these two parties had records to defend, while the Conservatives took the form of the insurgent or challenger party in both regions.

What did we expect?

Throughout much of the early campaign it was expected that the Conservatives would win a landslide majority, however, as the campaign progressed, this outcome became less and less likely. Over the course, the gap between the Conservatives and Labour shrank and some polling companies, notably YouGov, suggested we might be on course for another hung parliament. Polls showed a range of Conservative leads from between 1percent to 12percent, from between a hung parliament and Conservative losses through to a near landslide.

What differentiated many of these polls was how they dealt with youth turnout. Following the 2015 General Election – where polling companies’ overstated Labour support as a result of inaccurately high youth turnout predictions – polling companies modified their methodologies with some weighting by attention/interest in politics while others employed demographic weights – such as suppressing young, working class voters. A more detailed account is provided by Anthony Wells over at UKPollingReport. Those that adopted demographic turnout models tended to produce larger Conservative leads and thus youth turnout will be of vital importance come the election. Betting Markets and academic forecasters (such as Stephen Fisher, electionsetc.com) tended to show larger Conservative results than many polls suggested.

The Results

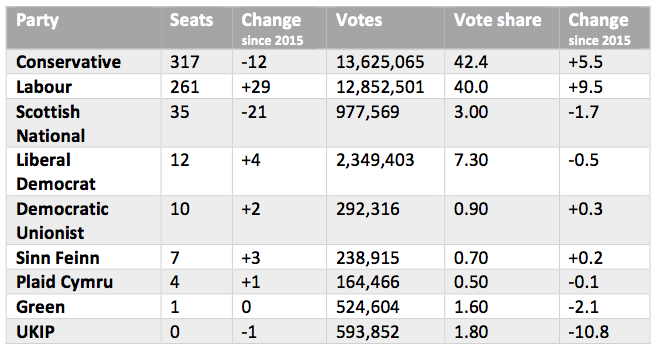

Note: Provisional (two undecided seats).

The first surprise of the night was the exit poll conducted by BBC, ITV, and Sky. It predicted that the Conservatives would lose their majority. Early on, Conservative officials spoke of their confusion: “the numbers just do not add up” they claimed. As the night progressed, however, it became clear just how accurate it was. The Conservatives gambled for a larger majority and were left wounded, Theresa May severely. The entire focus of the Conservative campaign were the leadership qualities of Theresa May. This initially played to her advantage, however, quickly became a clear line of attack by opponents. The failure of the Conservatives will therefore be perceived almost entirely as a failure of Theresa May. The Conservative Party is an autocracy tempered by assassination with little tolerance for losers. Her continued leadership is now in question, with the question being: when does the knife strike?

By contrast, Labour had a good night. While they were weaker in Northern England than should have been the case, they achieved an impressive result nonetheless. Against 2015, Labour have gained roughly 10% of the vote, an impressive feat resulting in the gain of numerous solid Conservative seats, including the likes of Canterbury. Corbyn’s performance was surprising to many, and no doubt strengthened his leadership within the party.

Scotland, as ever, proved to be an entirely distinctive election, with the Conservatives seriously challenging the supremacy of the Scottish Nationals, to become the second largest party. The Conservatives gained an impressive 13.7% of the vote and 12 seats while the SNP lost 21. The elections were a boon for Ruth Davidson, leader of the Scottish Conservative Party.

Wales emulated England: vote share gains and seat losses for the Conservatives, and an impressive performance by the Labour Party.

This election has seen the strengthening of the two party system in England and Wales, with the development of a three-party system in Scotland. The question now is whether Conservatives attempt to govern or seek another election. Only time will tell.

[1] The triple lock guaranteed that pensions would rise by either average earnings, inflation, or 2.5percent, whichever was higher. The double lock maintains the peg to earnings and inflation, however, removes the commitment to 2.5percent.[2] The amount of wealth someone can possess – including the value of their home – before they lose the right to free care was to be increased from the current £23,250 to £100,000. In effect, however much is spent on social care it becomes free once someone only has £100,000 remaining. The policy proved a disaster and was criticised from all corners, including party supporters, MPs, and Conservative-affiliated organisations, such as the Bow Group.[3] Indeed, Abbott had proved a gift to the Conservatives throughout the campaign given her embarrassing tendency towards gaffes. In one particularly memorable interview with LBC radio Abbott claimed that Labour would hire an additional 10,000 officers at a cost of £300,000 per year – it did not require much to realise that £30 per year per officer was not quite right.Photo source: http://www.dw.com/en/theresa-mays-conservatives-lose-absolute-majority-in-uk-parliamentary-elections-live-updates/a-39171597