By Wouter Veenendaal (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies)

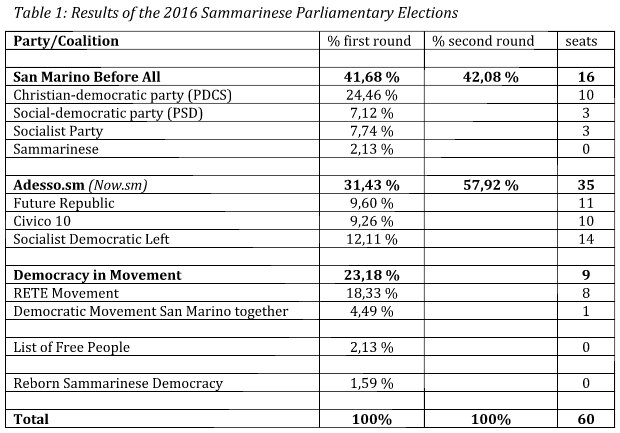

On 20 November 2016, elections were held for San Marino’s sixty-member legislature, the Consiglio Grande e Generale. Three electoral coalitions composed of various political parties contested the elections, as well as two minor independent parties. The previous elections had been held in 2012, when the San Marino Bene Comune (San Marino Common Good) coalition had won just over 50% of votes. However, the membership of the 2016 electoral coalitions – which have become a defining characteristic of Sammarinese politics since profound modifications to the electoral law were introduced in 2008 – changed significantly in comparison to 2012. In this year’s election, none of the three coalitions of parties succeeded in capturing a majority of votes, as a result of which a second round of voting (ballottaggio) was needed in order to determine which coalition would get the majority bonus of 35 out of 60 seats. This round, which was held on 4 December, resulted in a victory for the Adesso.sm (Now.sm) coalition, which consists of parties that before mainly had been part of the opposition. The results of the two voting rounds are presented in Table 1 below.

Mirroring Italian Politics

With a population of only 30.000 and a landmass of 61 square kilometers, the Republic of San Marino is one of the smallest countries in Europe, and in the world. The Republic is entirely surrounded by Italy, and political developments have always closely mirrored those of its larger Italian neighbour. Initial democratic development in the 1900s, the rise of fascism in the 1920s, and the return to multiparty democracy in the 1940s all occurred more or less at the same time as in Italy. In similar fashion, Sammarinese party politics has always strongly resembled those of its neighbor country. Just like in Italy, postwar politics in San Marino was dominated by Christian-democrats, communists, and socialists, but in contrast to Italy, from the mid-1940s to the mid-1950s San Marino was ruled by a coalition of communists and socialists. Just like in Italy, the collapse of communism and the fall of the Berlin Wall first sparked a fragmentation of the left, and subsequently a disintegration of the entire party system. And finally, just like in Italy, an electoral reform establishing a majority bonus for the coalition gaining a plurality of seats was introduced in order to curb fragmentation and the ensuing political instability.

The Political Effects of Smallness

While the party system dynamics of San Marino have hence ostensibly been very similar to those of Italy, in practice politics in the microstate is very different. This is principally a result of differences in scale: while Italy has a population of over 60 million, San Marino has a mere 30.000 inhabitants. This smallness creates a situation in which everyone knows everyone, and politicians and citizens are in constant direct contact. Virtually all Sammarinese citizens know at least some of their political representatives personally, for example as family members, neighbors, friends, or members of the same church or sport’s club. As a result, voting behavior is commonly based much more on personal relationships than on ideological convictions, and while most party labels suggest some ideological or programmatic orientation, in practice ideology plays a very minor role in Sammarinese politics. Correspondingly, rather than a totalitarian ideology, Sammarinese fascism was primarily a vehicle for some powerful families to return to power, and while paying lip service to communist principles, Sammarinese communism never was an ideologically inspired mass movement to fundamentally change the country’s society. In addition to the lack of programmatic politics, the proximity between voters and politicians has been a fertile ground for clientelism and patronage, which are a defining element of San Marino’s political system.

Fragmentation and Cooperation

The lack of ideologically inspired politics entails that party system fragmentation has become even more problematic in San Marino than in Italy. While only four parties gained parliamentary representation in the 1988 elections, this increased to six in 1993, and nine in 2006. Due to the smallness and relative weakness of programmatic politics, party split-offs and the emergence of new parties primarily occurred as a result of personal conflicts and infighting. However, the lack of ideologies also entails that to a much greater extent than in Italy, any combination of parties can together form an electoral or governing coalition. Past Sammarinese governments were often a patchwork of different parties, and since the introduction of the majority bonus in 2008, the same has applied to electoral coalitions. While the 2008 elections – the first under the new electoral rules – were contested by more or less coherent right-wing and left-wing coalitions of parties, in 2012 the main right-wing and left-wing parties (the Christian-democrats and social-democrats) formed a coalition together, and were opposed by a new set of parties. In the run-up to the 2016 election, the compositions and names of these coalitions changed once again.

The 2008 Crisis and Subsequent Corruption Scandals

With an economy that is to a very large extent based on banking and finance, San Marino was hit exceptionally hard by the 2008 global financial crisis. GDP growth plunged, and the country became a prime target in the subsequent international combat against fiscal evasion and tax havens. The Italian government strongly pressured San Marino to put an end to fiscal evasion, and when a major scandal unfolded at one of the microstate’s largest banks (the Cassa di Risparmio della Repubblica di San Marino), San Marino’s image as a malevolent tax haven was complete. In subsequent years, evidence emerged of the involvement of Calabrian mafia (‘Ndrangheta) in San Marino’s banks, and some of the country’s major politicians faced criminal charges for bribery, money-laundering, and corruption. Between 2013 and 2016, three senior Sammarinese politicians – Claudio Podeschi, Fiorenzo Stolfi, and most recently Gabriele Gatti – were arrested and convicted for involvement in various criminal activities. These developments sparked widespread protests in the country, and various popular movements against corruption emerged.

Protest Politics: The Rise of RETE

In response to the economic crisis and subsequent corruption scandals, some of the anticorruption movements transformed into new political parties that aim to transform the Sammarinese political system. One of these, Civico 10, has primarily campaigned on a social-democratic platform, and has sought to promulgate some institutional reforms in order to increase transparency and terminate conflicts of interest and pervasive clientelism. This party has also become one the main advocates for San Marino’s accession to the European Union. The other new party, the RETE movement (acronym for Renewal, Equity, Transparency, and Eco-sustainability) was founded online by environmental and civil rights activists, opposes EU-membership for San Marino, and is primarily supported by Sammarinese youth. RETE has been compared to Beppe Grillo’s Five Star Movement in Italy has been compared to Beppe Grillo’s Five Star Movement in Italy, and while it can indeed also be regarded as a protest party, RETE’s leaders also distanced themselves from parts of the Five Star Movement’s platform.

How Global Developments Impact a Tiny Republic

While RETE did not give an official voting advice for the ballottaggio, individual leaders of the movement have hesitatingly indicated their support for the Adesso.sm coalition, in an attempt to unseat the country’s political establishment. This tacit support seems to have worked, as most of RETE’s supporters appear to have endorsed Adesso.sm during the second vote. The victory of Adesso.sm entails that the two traditional parties in Sammarinese politics, the Christian-democratic PDCS and the social-democratic PSD, have now been voted out of office. Combined with the rise of RETE, this outcome of the Sammarinese elections therefore clearly fits the pattern of anti-establishment, protest politics that currently spreads across Western countries. Even in an extremely small and personalized political system like San Marino, the populist wave therefore seems to have instigated the dawn of a new era of party politics.

Photo Source: http://www.libertas.sm/notizie/2016/12/04/san-marino-elezioni-2016-ballottaggio-vince-adessosm.html