By Jo Saglie (Institute for Social Research, Oslo)

Incumbent parties tend to lose votes, in Norway as in many other West European countries. Nevertheless, the incumbent Norwegian government survived the 2017 parliamentary election. The government parties – the Conservative Party and the Progress Party – lost some seats, but remained in power. The main loser was not the government, but the largest opposition party. The stability is even more surprising, given that the Progress Party often is classified as a right-wing populist party. The party entered government for the first time four years ago, after the 2013 election. Political opponents hoped that support for the party would dwindle in office. That happened to the Socialist Left Party during its first terms in office (2005-13), but the Progress Party fared much better.

Political institutions

Norway has proportional representation, and the MPs are elected from 19 multi-member districts. Compensatory seats are used to improve proportionality, with a threshold of 4 %. This threshold only applies to the compensatory seats. A party can therefore win district seats with less than 4 % of the national vote. This has resulted in a multi-party system. Before the 2017 election, eight parties were represented in the Parliament.

Furthermore, Norway practices negative parliamentarism: There is no investiture vote – a government just have to avoid a vote of no confidence against it. This has contributed to a high frequency of minority governments. However, a majority government – the ‘red-green’ coalition of the Labour Party, the Centre Party and the Socialist Left Party – was in power from 2005 to 2013.

The ‘blue-blue’ government

The red-green coalition lost its majority in the 2013 election, and the new majority – the Conservatives, the Progress Party, the Christian Democrats and the Liberals – wanted a new government led by the Conservative party leader Erna Solberg. The Conservatives preferred a coalition of all four parties. However, the Progress Party on the one hand, and the Liberals and Christians Democrats on the other, are poles apart on many issues – especially environmental policy, and immigration and integration. Accordingly, the outcome of the 2013 election was a minority coalition of the Conservatives and the Progress Party. Since both parties use the colour blue to represent their party, the new coalition was nicknamed the ‘blue-blue’ government.

The coalition’s relationship with its supporting parties was regulated by means of ‘contract parliamentarism’: the four parties entered a formal agreement. The agreement described some basic values as a platform for the cooperation, some policy positions that they agreed on, as well as procedural matters on consultations and meetings between the four parties. However, the agreement gave the parties plenty of latitude. The government parties should first seek agreement with the two supporting parties, but the contract partners were also free to build parliamentary majorities with other parties, if they failed to reach agreement between them.

Many of the Progress Party ministers adapted easily to their new tasks, but some of them chose to play a different role. Especially, Sylvi Listhaug – the Progress Party’s Minister of Immigration and Integration – drove a wedge between her own party on the one hand, and the Christians and Liberals on the others. Even though the actual policy differences on immigration may not be that large (most parties want a restrictive immigration policy), her rhetoric on immigrants angered her opponents, pleased her supporters – and gave her much publicity. In other words, the Progress Party managed to appear with two faces: both a responsible government party, and a party with a populist appeal.

This put the Liberals and Christians in a difficult situation during the 2017 election campaign. Some of their voters detested the Progress Party in general and Listhaug in particular; others strongly disliked the red-green parties. The Liberals made it very clear that they preferred a blue-blue government to a red-green. The Christian Democrats were vaguer, and the leaders of both the Christian Democrats and Labour hinted at the possibility of some kind of cooperation between their parties, across the traditional blocs. A substantial share of the voters and party activists in both parties seemed to dislike this idea, and it was shelved.

The outcome

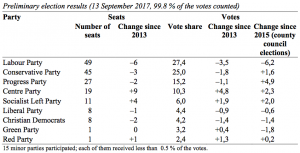

Source: The Norwegian Directorate of Elections.

The two government parties could be satisfied with the election result. Even though both lost some votes and seats compared with the previous parliamentary election in 2013, they made gains compared with the 2015 county council elections. The Liberals could also give a sigh of relief. The party scarcely reached the 4 % threshold, probably helped by tactical voting, but that was to be expected. The party has hovered around the threshold for many years. The Christian Democrats, on the other hand, had reason to be unhappy. It ended up even closer to the threshold than the Liberals, and got its worst election result since it became a nationwide party in 1945.

Four of the five opposition parties gained ground, but the Centre Party was the largest winner, doubling its support. The centre–periphery cleavage cannot be ignored in Norwegian politics, and the Centre Party is the main defender of the periphery. Presumably, the Centre Party owes its success to the government’s ‘modernization policy’. Centralization takes place in many sectors: municipal amalgamation, centralization of police stations, hospitals, military bases, and so on. Even though there may be good arguments for each individual reform, the joint impact provoked many voters in rural Norway.

The Labour Party, on the other hand, was the main loser of this election. As the main opposition party against a right-wing government, it had expected success – but ended up with its second worst election since the Second World War. The image of the Labour Party has traditionally been a ‘modernizing’ party, and even if Labour was critical of the ‘blue-blue’ reforms, it could not compete with the Centre Party’s intense opposition.

Neither managed Labour to compete very effectively with the Socialist Left Party and the Red Party on the ‘green left’ wing. The Socialist Left gained ground, and comfortably exceeded the 4 % threshold. The Red Party was below the threshold, but managed to gain a parliamentary seat for the second time in the Party’s history. Finally, the Green Party – which had won its first parliamentary seat in 2013 – defended this seat in 2017 but failed to reach the 4 % threshold.

What happens next?

Writing two days after the election, it is difficult to predict future developments. However, the Christian Democratic Party has made it clear that it does not want to enter any new agreement of cooperation. The party still prefers the ‘blue-blue’ coalition to a red-green one, but will not give any guarantees for the whole parliamentary term. If it cannot be a government party, it will be in opposition: the ‘in-between’ role has been too difficult. The Liberal Party has so far been less clear, and some Liberal politicians even want to become a coalition partner. However – unlike the situation before the election – the ‘blue-blue’ parties need support from both the smaller parties to build a majority. The ‘blue-blue’ parties will thus continue in government, but they need to seek support shifting majorities on different issues. How the Christian Democrats and Liberals will position themselves in this new situation, and whether the red-green parties will form a united front against the government, remains to be seen. The government, however, will probably have to give up the idea of a renewed contract parliamentarism, and instead follow the Norwegian tradition of ‘slalom parliamentarism’ – seeking support from the centrist parties on some issues, and from Labour on other issues.

Photo source: http://www.express.co.uk/news/world/852962/Norway-election-2017-result-polls-Erna-Solberg-parliamentary-elections-Jonas-Gahr-Store