By Ieva Hofmane (European University Institute)

On October 1, 2022, the Latvian general election was held. The results awarded seats in the Saeima, the parliament of the Republic of Latvia, to seven parties, including four newcomers. Prime Minister Krišjānis Kariņš’ New Unity party has captured almost 19% support, while the opposition Greens and Farmers Union was second with 12.44%. The new centrist electoral alliance United List — an alliance that resulted due to the split in the Greens and Farmers Union — was third with 11.01%. The New Unity party and United List have agreed not to cooperate with the Greens and Farmers Union if the sanctioned Latvian oligarch Aivairs Lembergs remains as their grey cardinal. Most likely, the new government will be formed by The New Unity party, United List, and National Alliance.

The pre-election context

The 2022 Saeima elections were mainly centred around four key issues – the pandemic, war in Ukraine, energy crisis, and LGBTQ+ rights.

The outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic took a toll on the Latvian economy. In addition, the government was often criticized over their decisions on lockdowns and the “mandatory” voluntary vaccination. This was an excellent soil for the emergence of anti-establishment/anti-vax parties. Moreover, the struggles of overcoming the pandemic turned out to be a great platform for old politicians to make a come back with their new political projects. Most notably, Ainārs Šlesers, a well-known oligarch and founder of many political parties in the past, made a comeback with his new project – Latvia First (Latvija pirmajā vietā).

After the events of February 24, parties had to make a clear stance against Russia. Although most parties condemned Russia’s invasion and fully supported Ukraine, some marginalized parties had difficulties addressing security matters. For example, while the all-time favourite Russian-speaking minority party Harmony (Saskaņa) lost about half of their members when they condemned Putin’s actions, support for the pro-kremlin parties Stability! (Stabilitātei!) and Latvian Russian Union (Latvijas Krievu Savienība) increased.

Almost all parties have indicated their intentions to reduce the extreme rise in energy prices and fight to ensure the country’s energy independence. The main focus is on widening the use of local and renewable energy resources. Some parties also expressed support for nuclear energy production; however, this is less likely to be implemented.

While societal support for LGBTQ+ rights slowly rises, petitions for a cohabitation law have been repeatedly signed, as well as the Constitutional Court of Latvia ruled that the Latvian Constitution entitles same-sex couples to receive the same benefits and protections afforded by Latvian law to married opposite-sex couples, the parliament has been reluctant to pass the Civil Union Law. These elections divided parties into camps – those with pro-traditional values and those supporting all families, including same-sex ones.

The current government has broken the longevity record, serving the full parliamentary term. However, it is not a sign of strength but a forced cooperation. As other government formations were not possible, countless compromises were made. Will Latvia put up with another “compromise government”?

Parties and their candidates

In these elections, 19 political parties and party alliances participated. Acknowledging that only roughly 1% of the electorate are members of a political party, this is an overwhelming amount of competitors. Moreover, the number of candidates was record-high – 1829 candidates, making the competition of 18.3 candidates per seat.

The Latvian party system’s brilliance (and misery) is that parties are rarely made out of thin air. Often, we observe “splitters” or “mergers”. In some cases, parties simply change their name from one election to another. The 14th Saeima elections were no exception.

The “centric-liberal block” includes two main forces. First, the New Unity (Jaunā VIENOTĪBA) is the party of Prime Minister Krišjānis Kariņš. It is composed of Unity (VIENOTĪBA) and five smaller regional parties. While in the 2018 elections, the party was punished and only got eight seats (~7% of the popular vote), the Kariņš “phenomenon” resulted in 2022 election support, predicting the party 21% of the votes. The utmost part of the For Development/For! (Attīstībai/Par!) has evolved from the Unity party. While in 2018, they got 13 seats, their ratings dropped significantly over the past four years. The financial scandals and other party elite drama did not go unnoticed; thus, in 2022, they were predicted a low success.

The “national-conservative block” includes the National Alliance (Nacionālā apvienība) and Conservatives (Konservatīvie), who previously experienced electoral success under the name New Conservative Party. The Conservative party is generally a splitter from the National Alliance, with a more liberal “touch”. The National Alliance has lived their long life mainly because of their ability to communicate the fear to its electorate that “Russians are coming”. However, when the Russians actually have come, and the fear of a similar invasion in Latvia is genuine, it does not seem that the party has a real plan. In that sense, the Conservatives were much more “pushier” in introducing a united school system, where education in the Russian language would no longer be available.

The “Russian block” consists of three leading players. First, The Latvian Russian Union (Latvijas Krievu savienība) is a pro-Moscow party led by the European Parliament member Tatjana Ždanoka. The pre-election polls indicated a slight increase in support compared to the previous elections, indicating that they may win some parliamentary seats. Second, the party Harmony (Saskaņa) has been the election over the past 11 years; however, the Latvian parties have established a Cordon sanitaire, and the party has never been given a chance to form (or even be in) the government. After the Harmony condemned Russia’s aggression, the support for the party rapidly decreased. While previously, the Russian-speaking minority nearly unanimously cast their vote for the party Harmony, it was expected that in 2022 the more radical/pro-Moscow voters would choose an alternative political force. The more radical Russian-speaking minority voters may have found peace in a new populist/pro-Moscow formation – in the party Stability! (Stabilitātei!).

A notorious split happened in March 2022 between the greens and the farmers. While the relationship had many red flags, they worked together in Latvian politics for 20 years. The Latvian Green Party (yes – the same one who was expelled from the European Green Party) and the Liepāja party (Liepājas partija) no longer wanted to cooperate with the sanctioned oligarch Aivars Lembergs, who has been the mastermind of the union over the years. The two parties formed an alliance under the name United List with the Latvian Region of Associations and the United List society, mainly composed of familiar old faces from the People’s Party (Tautas Partija). The Latvian Farmers’ Union stayed with Aivars Lembergs and his party For Latvia and Ventspils (Latvijai un Venstpilij). Moreover, the farmers invited the nearly dead Latvian Social Democratic Workers’ Party (LSDSP) to join their list. While the farmers kept the name Greens and Farmers Union, it is no longer the same union as we have known it before. The two political forces have similar ideological views and values; however, the United List has clarified that they will not cooperate with Greens and Farmers if Lembergs is still in the game. In the pre-election period, the oligarch expressed no intentions of leaving the political arena.

Lembergs is not the only oligarch who wants to stay relevant in modern Latvian politics – Ainārs Šlesers, another famous oligarch, made a comeback with his new political project Latvia First. Together with other old politicians, e.g., Vilis Krištopāns, who was Prime Minister of Latvia in the 1990s, Šlesers shows that voters seriously “suffer” from memory loss. If in 2011, society gathered to burn the puppets that symbolized the three little Latvian oligarchs, then now a disturbing number of voters want the oligarchs to return to active politics. Šlesers formed a rather weird team of the full spectrum, including family members, a priest from a sect, entrepreneurs with close ties to Russia, social media influencers and PR people. Party’s rhetoric is often compared to Trumpian-style populism.

It is worth mentioning that from 2009 to 2011, “Rīdzene talks” were recorded by the Corruption Prevention and Combating Bureau (KNAB; Korupcijas novēršanas un apkarošanas birojs) and leaked in the magazine “Ir” in 2017. The materials corroborate suspected corruption and abuse of power done by the former Minister of Transportation Ainārs Šlesers, the Mayor of Ventspils Aivars Lembergs, and former Prime Minister Andris Šķēle. Furthermore, the conversations reveal their schemes for controlling democratic institutions and the press, as well as their interest in nominating candidates favorable to Moscow.

Continuing with populism, perhaps you remember the 2018 election star with 16 seats – Who Own’s the State (KPV LV). Well, the party started to split about two months into the parliamentary term. The party renamed itself For a Humane Latvia (Par cilvēcīgu Latviju) and, for the elections, formed an alliance with a minor party under the name of Union for Latvia. One of KPV’s most familiar faces, Aldis Gobzems, created his own party For Each and Every (Katram un Katrai) – one previously known as Law and Order (Likums un kārtība). The self-proclaimed alpha male leader and his party fit the description of an anti-establishment party. Just like populism handbooks describe them. Finally, the brothers Kaspars and Sandis Ģirģens created their populistic party Republic (Republika), where most of the original KPV LV people joined them. However, a great success for them was not predicted. It is worth mentioning that about ¼ of KPV LV 2018 election candidates participated in the 2022 elections. Only this time, it was done from 11(!) different party/party association lists. A considerable part of the elected KPV LV politicians joined the Šlesers party, hoping to survive another parliamentary term.

On a more positive note, a green (in its true sense) European/Scandinavian style social democratic party, Progressives (Progresīvie), has entered the arena. The party has originally emerged due to a split in LSDSP. While they only gained 2.6% of votes in 2018, their chances of getting into the parliament in 2022 severely increased. Both their candidates and electorate are located in the younger part of society.

The minor parties with low support include TAUTAS KALPI LATVIJAI (Servants of the People for Latvia), SUVERĒNĀ VARA (Sovereign Power), Kristīgi Progresīvā Partija (Christian Progressive Party), Tautas varas spēks (Strength of people power), Vienoti Latvijai (United for Latvia). These parties have unsuccessfully participated in the elections previously. However, it was done under a different name and/or a brand.

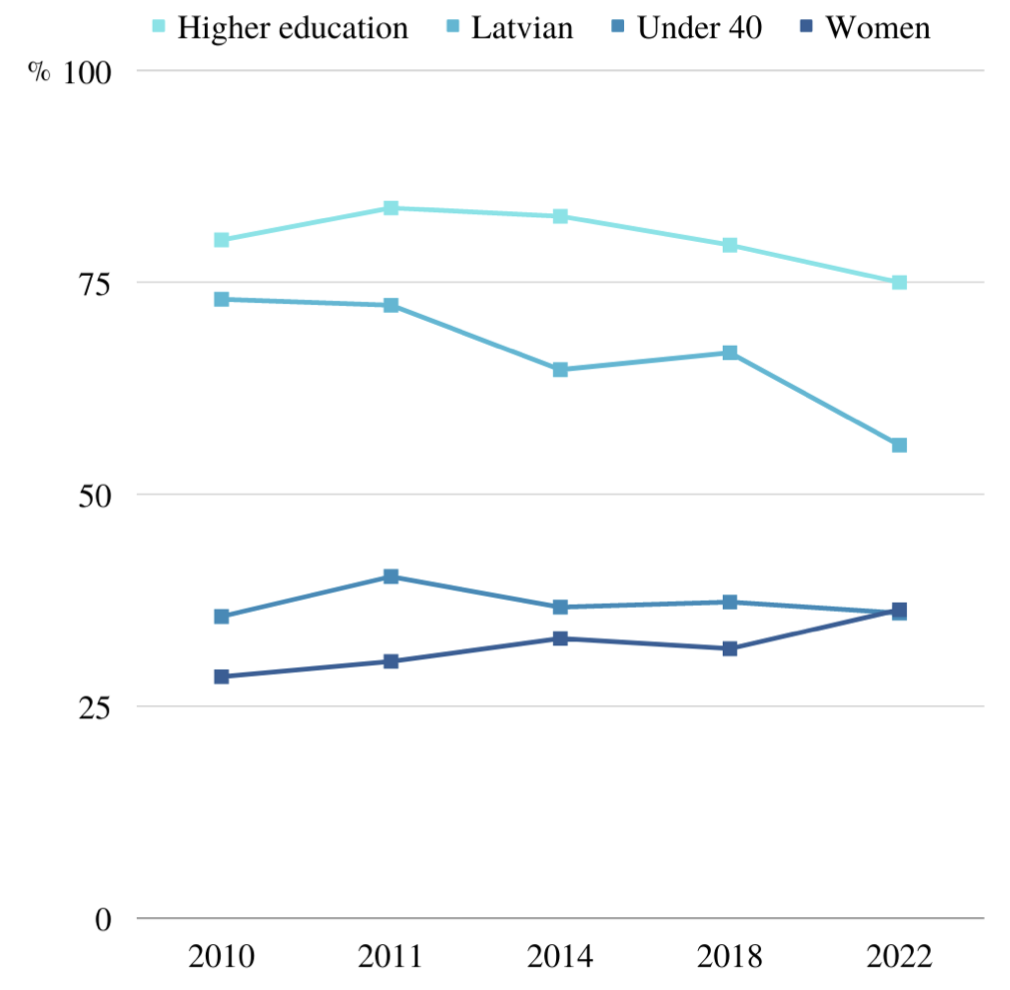

As for the candidates, we see disturbing tendencies in the social-demographic characteristics (See Figure 1). In comparison to previous elections since 2010, there were a lot more candidates who had not attained higher education. If in 2011, 84% of candidates had attained higher education, in 2022, only 75% of the candidates were university graduates. The number of nominated candidates who stated that they are Latvians by ethnicity has also decreased significantly. Only 55.8% of candidates indicated their ethnicity as “Latvian”, 8.8% indicated another ethnicity, but 35.4% did not indicate their ethnicity at all. Furthermore, most candidates are between the age of 41 and 60 (49%), and only 36% of the candidates would be considered young (under 40). It should be noted that only 10% of candidates are under 30. Compared to other European countries, the representation of women in the Latvian parliament is among the highest. Of course, whether women’s substantive interests are well represented is another matter. This year, 665 women were nominated, which is 36.4% of all candidates.

Figure 1. Candidate socio-demographic characteristics across years 2010-2022

Data source: Central Election Commission (2010-2022). Calculations done by the author.

Turnout

The Central Election Commission’s data shows that in comparison to previous years, the turnout has increased to 60% of the electorate. As the Russian-speaking minority voter was often disappointed and did not show up at the ballot box, it seems that parties successfully managed to mobilize the Latvian-speaking voters. Considering that the turnout was predicted to be below the 50% mark, this is a spectacular outcome.

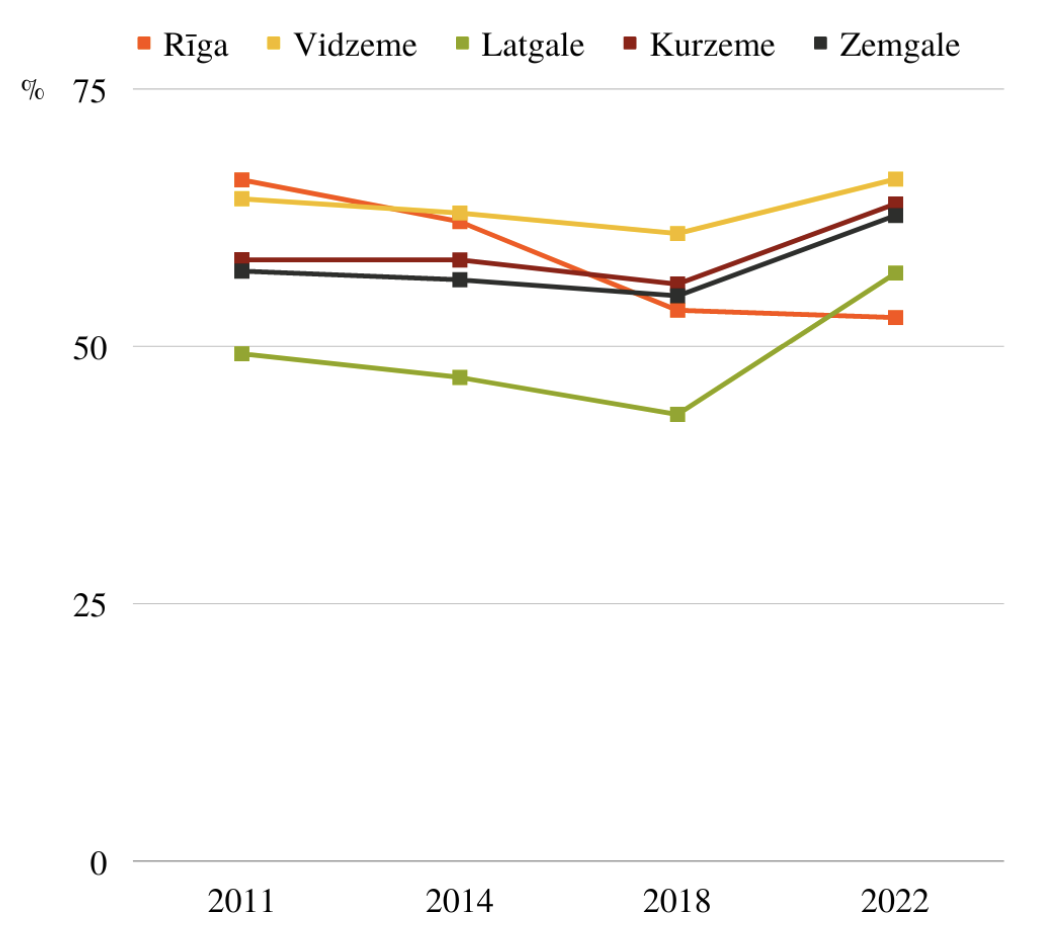

As for the turnout across electoral districts (see Figure 2), the only district where voter activity decreases with each election is the capital city, Rīga. I would argue that this reflects the disappointment of the Russian-speaking voter who used to vote for party Harmony. On the contrary, the populist pro-Moscow party Stability! managed to encourage the Russian-speaking voter in Latgale to attend the elections. Latgale – the district that shares borders both with Russia and Belarus – unfortunately, is notoriously famous for low turnout; however, this year, we see a big jump in voter activity, surpassing voter activity in Rīga. While higher voter turnout may be interpreted as a good sign, I would argue the exact opposite in Latgale`s case. We see that parties who gained the most votes in Latgale are pro-Moscow parties, indicating a severe polarization across society on condemning Russian aggression in Ukraine.

Figure 2. Saeima elections turnout across electoral districts 2011-2022

Data source: Central Election Commission (2011-2022). Calculations done by the author.

Results

The Central Election Commission wrapped up the ballot counting from 1055 polling stations at 9 PM on October 2. Seven parties have crossed the 5% threshold, with For Development/For! falling short only by a margin of 0.03%.

The apparent election winner is the party of Prime Minister Krišjānis Kariņš – The New Unity (18.97% votes). Then follow the Greens and Farmers (12.44%), United List (11.01%), National Alliance (9.29%), Stability! (6.8%), Latvia First (6.24%), and Progressives (6.16%).

The votes translate into 26 seats for The New Unity and 16 for the Greens and Farmers. 15 seats for United List. 13 seats for National Alliance. 11 seats for Stability!. 9 seats for Latvia First, and 10 seats for Progressives.

The previous election winner since 2011 – the party Harmony – will not be seen in this parliamentary term. If in the previous elections it received 19.8% of votes (23 seats), then for these elections it received only 4.81% of votes. Moreover, government parties, apart from The New Unity, were punished harshly. Conservatives, who previously got 16 seats, and For Development/For!, who previously got 13 seats, did not cross the 5% threshold. National Alliance received the same amount of seats as before.

Nevertheless, The New Unity party was rewarded with a striking amount of 18 seats. While the government was heavily criticized, the crisis mode leadership of Kariņš and the long-term work of the minister of foreign affairs Edgars Rinkēvičs was seen as successful in the eyes of voters.

Three intriguing conclusions may be drawn from the results:

1. While The New Unity is the election winner, it does not mean that most voters were satisfied with the work of the 13th Saeima and government. We see that 61 of the seats are divided between opposition and newcomer parties.

2. The split-up of the greens and farmers brought success, as in the previous elections (when parties were in an alliance), they only got 11 seats, but now they have scored a total of 31 seats.

3. The long-term divide between Latvian and Russian-speaking minority parties seems to be diminishing. The elected parties start to represent the “traditionally” Western left-right ideological spectrum. If previously parties had to form a coalition along the nationality aspect, then the day after the elections, we see parties discussing their cooperation based on ideological/programmatic goals.

Potential coalition

At the moment, the most viable composition of the new coalition would consist of The New Unity, National Alliance and United List. All of the “state-minded” parties have assured that they will not cooperate with the Greens and Farmers Union if Aivars Lembergs remains as the grey cardinal.

The coalition may also include Progressives; however, they have major ideological disagreements both with The New Unity and the National Alliance. If The New Unity is pro-fiscally responsible politics, then the Progressives are pro-socially responsible. The disagreement with National Alliance concerns the “traditional” values, most notably – the chance that the 14th Saeima will pass the Civil Union Law.

Photo source: LETA