By David M. Willumsen (University of Innsbruck)

Since (at least) 2001, the question of immigration has been a key issue in Danish politics, with the Danish People’s Party (DPP) being successful in shifting public policy on this topic significantly to the right, and helping keep the center-right in power for all but four years in the period since then. In the 2015 election, this success was crowned by the DPP achieving its all-time best results in a general election, almost doubling its vote share, to 20,6%, after winning 26,6% of the vote in the 2014 European Parliament election. In doing so, the DPP displaced the Liberals (Venstre) as the second-biggest party in the country, and as the biggest party on the Right. However, despite this success, the Danish People’s Party did not seek to enter government, and instead the Liberals formed a single-party government, even though they had obtained only 19% of the seats in the Folketing. In November 2016, the Conservatives and the Liberal Alliance joined the government, which after this still only controlled just under 30% of the parliamentary seats.

The Social Democrats responded to the DPP’s sustained success by shifting their policies on immigration sharply to the right, seeking to win back working-class votes which they believed had been lost of the DPP due to these voters’ critical views on immigration. In both the 2019 European Parliament (EP) and Danish general election (held 10 days apart), the DPP preformed significantly worse than previously. In the EP elections, the DPP’s was reduced from four to one MEPs, and in the general elections, its vote share dropped by almost 12 percentage points, reducing it from 37 to 16 MPs.

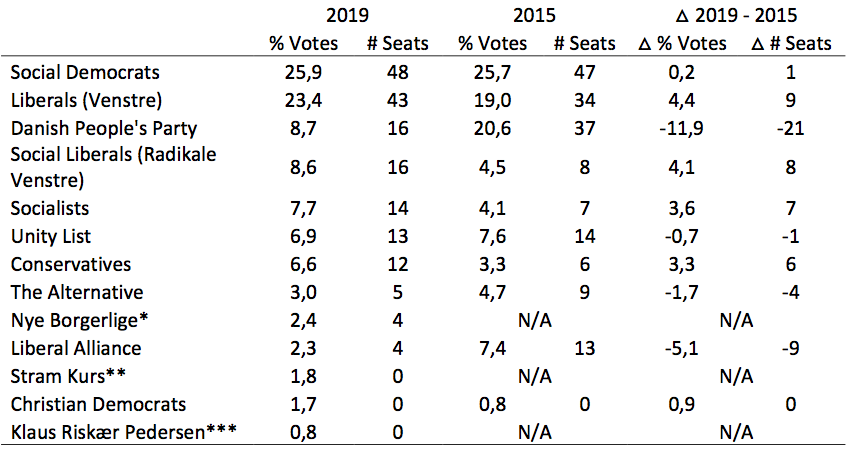

While the DPP was the clearly the biggest loser in the election, a number of parties can lay claim to success (see Table 1). On the left, the Social Democrats marginally increased their vote share, and picked up a single seat; however, the large increase of the vote share of the ‘Red Bloc’ was driven by the Social Liberals and the Socialists, who both substantially improved on their performance in the 2015 election, picking up eight and seven seats, respectively. The far-left Unity List lost a single seat, and the Alternative lost four. On the right, the party of the outgoing Prime Minister, Lars Løkke Rasmussen, had the biggest absolute improvement of any party, picking up nine seats, while the Conservatives doubled in size (albeit from a low base). The third party in the outgoing coalition government, the Liberal Alliance, serving in government for the first time, lost nine of their 13 MPs, and only barely cleared the two-percent threshold.

Table 1: Election results in Denmark, 2015 and 2019

The Faroe Islands and Greenland each elect two MPs; however, these have their own party systems. Three of the elected MPs would be expected to support a centre-left government, and one a centre-right government.

* Lit. ‘The New Bourgeois’; the party does not yet have an established translation of their name into English.

* Lit. ‘Tight Course’; however, ‘Hard Line’ better conveys the meaning of the name. The party does not yet have an established translation of their name into English.

*** Party shares name with its founder.

Four parties not represented in the 2015-19 Folketing sought to enter at this election, but only one was successful: Nye Borgerlige, an anti-immigration and pro-small state party, gained four seats. Stram Kurs, which had shot to (media) prominence after its leader, Rasmus Paludan, had successfully incited riots through stunts such as burning the Koran (something which he denied having done during the campaign, despite having uploaded videos of himself doing so to YouTube), missed the two-percent threshold, as did the Christian Democrats, which came within 191 votes of winning a district mandate, which would also have entitled them to two additional, compensatory seats. Noteworthy was the large (by Danish standards) number of wasted votes, with 4,4% of votes cast for parties and candidates which did not achieve any representation in the Folketing.

While the so-called ‘Red Bloc’ were very successful in the election, government formation will be complicated by the source of that success: While the move of the Social Democrats to the right on immigration may have helped them win back votes from the DPP, this came at the cost of losing some of their more immigration-friendly voters to the Socialists and the Social Liberals. These parties will, with some justification, claim that the left-wing majority in the new Folketing is down to their electoral performance, and not that of the social democrats, whose vote share stagnated.

The 2011-15 government led by the Social Democrats was dogged throughout its term by accusations of broken promises, with many of these having their roots in the coalition negotiations with, in particular, the Social Liberals. The leader of the Social Democrats, Mette Frederiksen, is acutely aware of the risk of a repeat of this scenario, in particular on the topic of immigration, where she will be faced with strong demands from the other parties in the Red Bloc to shift immigration policy towards the left, something which she has publicly ruled out. While the coalition formation process is informal in nature, with no investiture vote required to take office, building a sustainable coalition will still be a complicated task.

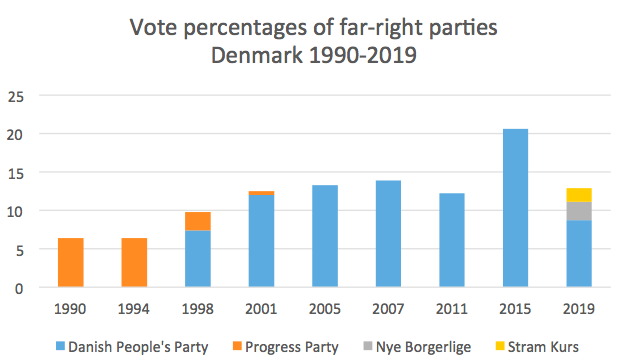

Figure 1: Vote share of far-right parties

While the collapse of the DPP was much featured in headlines, it is almost certainly too early to speak of a collapse of the far right in Denmark. While the far-right vote splintered this time round, the DPP having held an essential monopoly on this part of the electoral space since seeing eclipsing the Progress Party in the late 1990s, as can be seen in Figure 1, when the vote share of the various far-right parties are combined, a picture of significant stability since the DPP entered the political scene in the late 1990s emerges. In the four elections from 2001 to 2011, far-right parties obtained on average 13% of the vote – almost exactly what such parties achieved in 2019. While in the future the DPP may have to compete with, in particular, Nye Borgerlige, for votes, there is little to suggest that the far-right is not alive and kicking in Denmark.

Photo source: https://www.thelocal.dk/20190605/live-denmark-awaits-results-of-general-election