By Hakan Yavuzyılmaz (Başkent University)

On May 14th Turkish citizens headed to the polls to cat their votes both for parliamentary and presidential elections. The elections saw a historic turnout, reaching to 87%. Such an extensive participation was both due to tight race between the main presidential candidates and high level of polarization in the country. The candidate of People’s Alliance Recep Tayyip Erdoğan received 49.5% of the votes and his main competitor Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu who is the joint candidate of Nation Alliance received 44.9% of the total votes (Table 1). A third nationalist candidate Sinan Oğan surprisingly received 5.2% of the total vote and currently plays the role of kingmaker for the upcoming runoff.

For the first time in his three presidential contests Erdoğan’s vote was kept below 50% by the opposition. With these results, Turkish voters will cast their votes in a runoff election for the presidency on 28th of May. Nevertheless, the prospects for an opposition victory remains weak as the vote margin between Kılıçdaroğlu and Erdoğan is higher than pre-election polls estimated. Erdoğan’s alliance majority in the parliament further derails the prospects of opposition victory in the upcoming runoff elections.

Table 1. The results of presidential elections

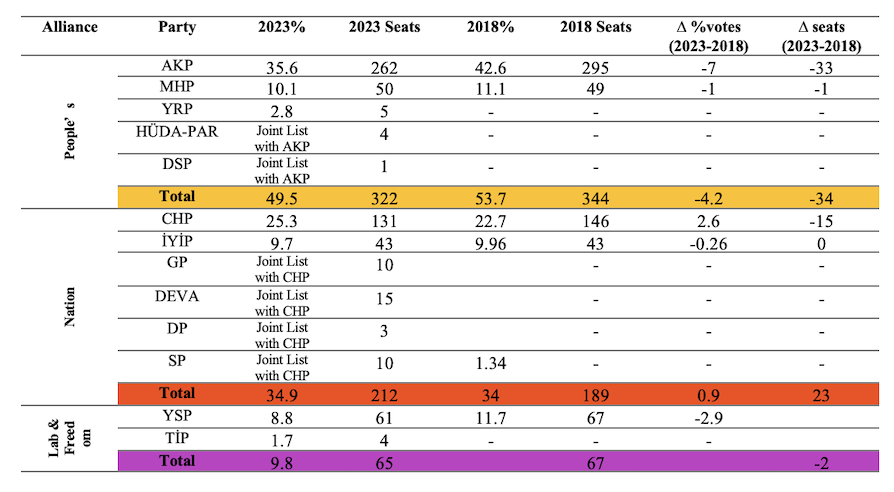

The results of the parliamentary elections show that the ruling People’s Alliance holds legislative majority in the 600-seat parliament but continues to remain below required majority for constitutional change. Although Erdoğan’s AKP remained the largest party (with 35.6% of the votes and 268 seats), it experienced a significant loss compared to 2018 elections. Thanks to Erdoğan’s severely polarizing campaign most of AKP votes were shifted to other components of People’s Alliance which include ultra-nationalist MHP and other right-wing parties such as pro-Islamic YRP. As the main opposition party, the Republican People’s Party CHP received 25.3% of the votes. Thanks to the joint list strategy of the Nation Alliance, small parties such as DEVA and GP received legislative seats which are highly disproportionate with their votes. Overall, the results of the legislative elections show a much more fragmented legislature dominated by right-wing political parties. Table 2 shows the results of the legislative elections in comparison with 2018 legislative elections.

Table 2. Results of 2023 legislative elections in comparison with 2018 elections

What was different this time?

The results show that for the first time Erdoğan remained below 50% threshold and his AKP lost significant share of votes which pushed the party’s vote share nearly to its 2002 performance. There are important dynamics at play which enabled opposition to achieve these results which are obviously not sufficient for ousting an authoritarian incumbent through elections.

Most important difference between 2023 and 2018 elections was the significantly derailed performance legitimacy of the incumbent AKP. The most important dynamic that led to the demise of ruling block’s performance legitimacy is the ongoing economic crisis which is directly related with the poor management of the economy, especially following Turkey’s transition to a hyper-presidential system. AKP’s winning formula has been to combine a relative economic success with effective non-programmatic distributive politics such as clientelism and patronage. However, rising inflation and depreciation of Turkish Lira against foreign currencies pull down the incumbent’s performance legitimacy. Furthermore, government’s inadequate response to disasters such as forest fires last year and most recent earthquakes that took over 50,000 lives further derailed the performance legitimacy of Erdoğan and his AKP in Turkey.

The aforementioned dynamics intensified the coordination efforts of opposition parties. Since 2018, the main opposition parties (CHP and İYİP) institutionalised their coordination alongside expanding the alliance by including center-right splinter parties from AKP (DEVA and GP). They held regular meetings and prepared a joint proposal for transition to ‘strengthened parliamentary system’. They also held informal talks with pro-Kurdish HDP during this process. More importantly, for the first time, the opposition was able to nominate a joint candidate Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu against the authoritarian populist Erdoğan. Beside the joint platform and candidate, the People’s Alliance also held regular meetings to increase their coordination for the prevention of possible election day fraud.

Alongside the Nation Alliance two other pre-electoral alliances competed for elections: the Labor and Freedom Alliance and the ATA Alliance. The latter nominated a joint candidate Sinan Oğan while the former declared its support for Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu and did not nominate a candidate for the presidential race. Overall, compared to 2018 presidential race where there were multiple candidates competing against Erdoğan, recent elections saw a more institutionalized form of pre-electoral alliance and opposition coordination in Turkey.

A third important difference between 2018 and 2023 elections was the campaign discourse of the alliances and candidates. Erdoğan and his alliance sticked with his intensively polarizing campaign discourse including demonization of the opposition along ultra-nationalistic and religious lines with direct attacks against Kılıçdaroğlu. On previous rounds of electoral contests, the opposition’s campaign discourse was centered on anti-Erdoğanism and directly confronted his polarizing discourse with a similar polemical tone. Nevertheless, in this campaign period the opposition centered its campaign to positive campaigning by emphasizing democratization and economic development with slogans such as ‘spring will come’.

Despite a more institutionalized form of opposition coordination, derailed performance legitimacy of the incumbent, and opposition’s positive and inclusive campaign, the outcome of the elections shows that even if Erdoğan lost the presidential race in the first round, he and his ruling block remains strong. There are several reasons at play that can be put forward for explaining Erdoğan’s resilience: (1) a heavily skewed electoral playing field to the advantage of ruling alliance, (2) AKP’s strong party organization, and (3) problems regarding opposition coordination.

Still competitive but unfair

Apart from some minor election day irregularities, the elections were held in a peaceful manner. There were numerous complaints against the results but currently there seems to be no large-scale electoral fraud that had a major impact on the outcome. Yet, elections failed to fulfil democratic standards. There were several issues that disrupted the electoral integrity.

Like the previous rounds, the race was highly competitive. Several opposition parties and pre-electoral alliances campaigned freely. Nevertheless, there were several issues that made the contest an unfair one. First and foremost, significant deterioration of judiciary independence in the country has directly affected the elections. The closure case against the pro-Kurdish HDP forced the party to enter elections under a different brand (Green and Left Party). Secondly, the İstanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu who defeated Erdoğan in recent local elections was sentenced to prison and remained under the threat of a political ban over the course of the election period. Such moves by the incumbent significantly altered the dynamics of the competition.

During the campaign process Turkish media was also significantly biased against the opposition. This was both due to the indirect control of the mainstream media by oligarchs who have close ties with Erdoğan and partisan control of the public media. For example, during the campaign period while Erdoğan received 48 hours of airtime on the TRT News; the main opposition candidate Kılıçdaroğlu has 32 minutes of total appearance. Erdoğan also significantly instrumentalized public resources for his campaign. For instance, he nominated critical ministers as candidates who extensively instrumentalized ministerial resources during the campaign period. For instance, the police remained intentionally ineffective and did not take any action against a violent attack during Ekrem İmamoğlu’s rally in Erzurum.

Beside these advantages, the ruling block used its legislative majority to alter the election law to its advantage. One of the most significant amendments is the one that forced opposition parties to issue joint candidate lists to maximize their number of seats in the parliament. Such a move significantly disrupted the coordination of the opposition parties. For instance, CHP lost seats to minor alliance partners and some of the ardent supporters of CHP became sceptical to see some conservative candidates which are previously affiliated with AKP within the CHP lists. Erdoğan also put forward several legislative amendments which directly targeted his constituency who got hard hit by the ongoing economic crisis such as increasing the minimum wage and providing early retirement.

Still strong and still there: the AKP machine

Even though the results of legislative elections show an apparent decline in AKP’s vote shares and there is an increasing gap between the votes of Erdoğan and his party, AKP continues to remain a very strong organization. AKP organization continued to selectively distribute rewards to its voters and remained highly effective in terms of door-to-door canvasing. Party organization was not only effective for maintaining clientelistic party-voter linkages but also it worked as an effective mobilization machine. For instance, several interviews with ballot box committee members indicate that compared to opposition’s presence at the ballots, AKP was more successful in terms of mobilizing its membership base on the election day.

Unity in disunity: opposition coordination under competitive authoritarianism

Defeating incumbents in competitive authoritarian regimes is not an easy task. Opposition coordination in the form of pre-electoral alliances is a necessary yet insufficient condition for ousting elected autocrats by elections. The opposition in Turkey managed to form such coordinative pre-electoral alliance. Two alliances were formed, and these two alliances endorsed a single presidential candidate Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu. Such a move was unseen in Turkish politics which remained highly polarized around formative social cleavages. Despite ruling blocks’ efforts to emphasize these formative rifts and disrupt the opposition coordination, the opposition parties managed to hold the fragile pre-electoral alliance. Nevertheless, there were several problems that hindered the potential of opposition coordination in Turkey.

First and foremost, the opposition alliances include several parties with different ideological leanings, ranging from pro-Islamist SP, social democratic CHP to nationalist İYİP and pro-Kurdish HDP/YSP. Especially within the Nation Alliance there is also huge asymmetry in terms of electoral strength of political parties. Despite this asymmetry, Nation Alliance’s decision-making mechanism equalized the decision-making power among these parties. This gave highly disproportionate power to smaller parties. Secondly, even though the opposition achieved some form of routinization in terms of coordination, the joint candidate nomination was left to the last minute and no specific mechanism was used. Nearly two months before the elections, the İYİP pushed for Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu and Mansur Yavaş as candidate of the alliance since all the pre-election surveys showed him as the most popular potential candidate. CHP and other minor parties’ insistence on Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu (the leader of CHP) led to a crisis which culminated into the withdrawal of İYİP from the alliance. Even though İYİP returned to the table two days later, such a crisis significantly increased the pessimism of nationalist voters regarding the future stability of the alliance in case of a victory.

Last but not least, the Nation Alliance proposed a collective leadership formula. In case of a victory all six leaders of the parties that make up the Nation Alliance plus the mayors of İstanbul and Ankara are promised with vice presidency. Such an arrangement not only gave disproportionate power to highly marginal parties within the alliance but also increased the perceptive fragility and potential inefficiency of the alliance among undecided voters.

The amendment to the electoral law which forced the small alliance members to run through joint lists further disrupted the coordination among the opposition parties. Although Nation Alliance managed to coordinate in some parliamentary districts, there were no coordination with Labor and Freedom Alliance at all. On the contrary, Erdoğan’s People’s Alliance’s members AKP, MHP and YRP decided to contest legislative seats through separate lists. Such a move seems strategic as the conservative-nationalist defectors from AKP managed to find new homes within the People’s Alliance instead of shifting towards opposition which was severely demonized by AKP and MHP through an ultra-nationalistic polarizing campaign discourse.

The Nation Alliance also could not effectively counter the nationalistic attacks such as opposition’s alleged linkages with terrorist groups. Against intensifying demonization of the opposition candidate with ultra-nationalist tones, the opposition sticked with positive campaigning which further disenchanted nationalist voters. Although the Nation Alliance proposed a joint platform as its election manifesto it was not transmitted effectively and remained futile against incumbent’s ultra-nationalist and demonizing campaign.

Overall, the opposition alliance was not effective in terms of coming up with a decision-making mechanism that showed actual and prospective stability; supplying a winner joint candidate for presidential contest and joint lists that can bring legislative majority, mixing positive campaigning without disenchanting nationalist voters.

What the future holds?

Heading to a runoff contest, current elections are highly prominent for future regime trajectory of Turkey. The country has been in a rapid democratic backsliding process and has been categorized as a competitive authoritarian regime where there is real electoral competition, yet the electoral playing field is heavily skewed to the benefit of the incumbent. Obviously, the opposition remains demoralized by the results of the first round. The opposition candidate is currently facing the challenging task of mobilizing nationalist voters who are unhappy with both Erdoğan and Kılıçdaroğlu. To this end, Kılıçdaroğlu significantly altered his campaign discourse along nationalist lines. At the time of writing, the runoff elections’ kingmaker ultra-nationalist Sinan Oğan’s support for the opposition remains uncertain. Even in case of such a support, it still remains a prominent challenge for the opposition to mobilize nationalist voters without disenchanting Kurdish voters. On top of all these, the election day performance of the Nation Alliance also significantly demoralized opposition voters. Even though there is still a chance to electorally beat Erdoğan, the opposition definitely faces an uphill battle. Erdoğan’s victory with high margin, will also jeopardize the opposition’s chances for success in the upcoming local elections on March 2024.

Photo source: https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/turkey-election-runoff-2023-what-you-need-know-2023-05-18/